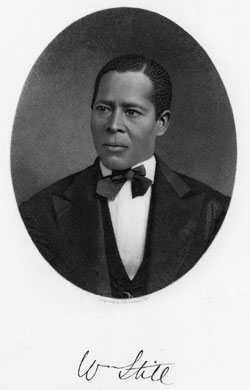

Blockson Collection preserves abolitionist’s legacy

| At a time when slavery was still legal in the United States, African-American abolitionist and businessman William Still rallied to the call for freedom. He personally provided room and board for many Africans who escaped slavery and stopped in Philadelphia on their way to free states or Canada. Working with the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery’s Vigilance Committee, he raised funds to assist runaways and arrange their passage to the North. And he was instrumental in financing several of Harriet Tubman’s trips to the South to liberate enslaved Africans.

Today, Still’s book, The Underground Railroad, is known worldwide. According to Diane Turner, curator of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple, the work “is important not only for the meticulous record it establishes, but also because it demonstrates that Blacks had intellectual ability and were active participants in their struggles for freedom.” |

Photo courtesy Blockson Collection

|

|

“To keep a record of the activities of the Underground Railroad was a risk,” said Turner. “Prior to the Civil War, helping people escape slavery was against federal law.” Now, as Temple recognizes Black Heritage Month, the Blockson Collection is helping to ensure Still’s legacy endures by digitizing and displaying his personal papers. Covering 1865 through 1899, the archive contains 140 letters and 14 photographs that are in demand among scholars and researchers. However, time and natural wear have caused some of the items to decompose. Now kept in mylar and acid-free folders, letters to his family are almost illegible, their paper deteriorating at the edges. Supported by a $46,777 grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities’ Save America’s Treasures program, the Blockson Collection will preserve the papers and related historical documents through a digitalization process, which will allow the artifacts to be viewed online by scholars across the globe. Among the papers are letters from Still to his daughter, Caroline, a student at Women’s Medical College. Like most modern exchanges between parents with children away at school, Still’s letters encouraged her to keep up with her studies — and often “He would routinely send $5 for her expenses, and that was a lot of money back then,” said Aslaku Berhanu, librarian at the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American collection. “These letters reflect William Still on a personal level,” added Turner. “His letters to his daughter are so personal, they show that he was a normal father, an ordinary man who ended up doing something extraordinary. He helped Americans of African descent have a voice.” |

|