Temple researchers show drug therapy helps Alzheimer’s disease in mice

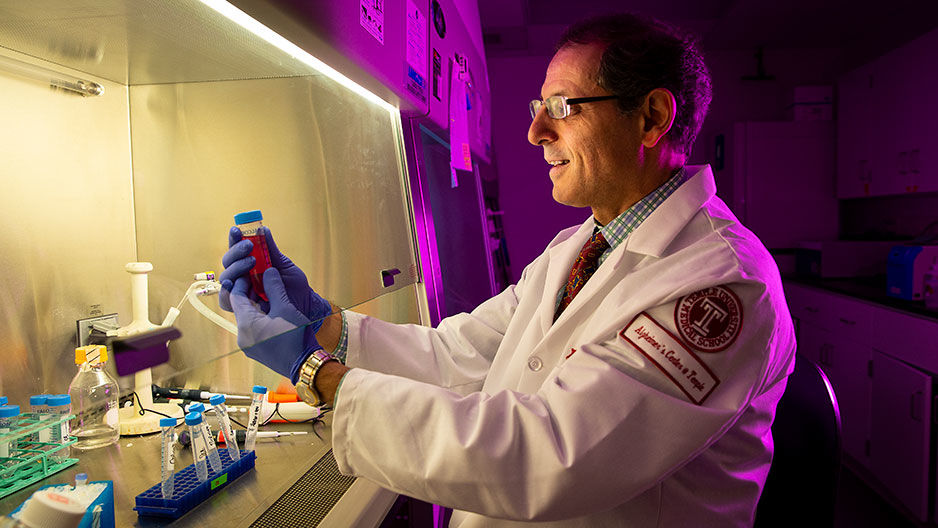

Domenico Praticò and his team studied the drug molecule’s effect on the brain’s ability to stave off protein build-up and came away with promising results.

Scientists at Temple University’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine continue to take action in the fight against Alzheimer’s disease.

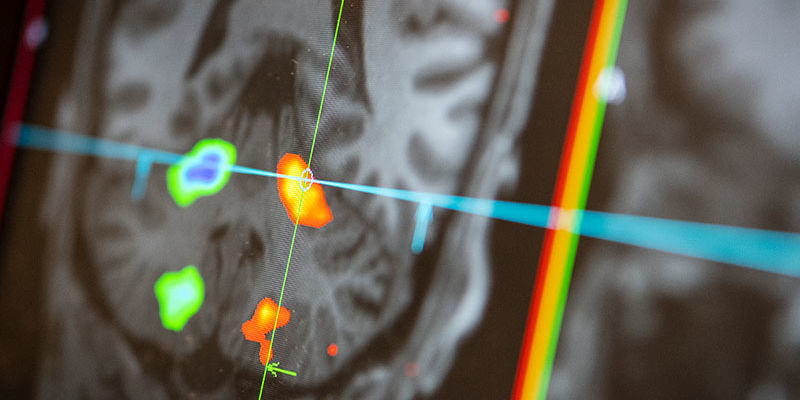

In a study published Jan. 21 in the journal Molecular Neurodegeneration, the researchers describe results that suggested that a new drug treatment can be effective in preventing the buildup of certain proteins that occur in brains stricken with the disease.

Domenico Praticò, the Scott Richards North Star Charitable Foundation Chair for Alzheimer’s Research, Professor in the Departments of Pharmacology and Microbiology, and Director of the Alzheimer’s Center at Temple (ACT) at the Katz school served as the senior investigator on the new study.

Praticò’s team treated mice with the drug, known as chaperone therapy, and measured the levels of certain proteins associated with Alzheimer’s. The drug treatment did in fact disrupt the deteriorating processes that occur, and the mice’s brains remained healthier.

“Our chaperone drug specifically restored levels of a sorting molecule known as VPS35,” said Praticò. The molecule is critical in the cellular processes that remove the amyloid beta and tau proteins—which are found in greater quantities in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s—before they can build up.

The results are promising, particularly because the therapy has a track record with other diseases, having gone through the long, complex and expensive process of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, according to Praticò.

“Relative to other therapies under development for Alzheimer’s disease, pharmacological chaperones are inexpensive, and some of these drugs have already been approved for the treatment of other diseases,” Praticò explained, adding that with this type of therapy, the approach is different.

“These drugs do not block an enzyme or a receptor but target a cellular mechanism, which means that there is much lower potential for side effects,” he said. “All these factors add to the appeal of pursuing pharmacological chaperone drugs as novel Alzheimer’s treatments.”

—Gale Morrison