The future of affirmative action: Experts explain the upcoming Supreme Court cases

Temple experts explain the two latest lawsuits challenging affirmative action at higher education institutions.

In June, the Supreme Court will decide on two affirmative action cases that could potentially alter the landscape of higher education. The plaintiff in both, Students for Fair Admissions, is challenging race-conscious admissions at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina. The nonprofit membership group believes that affirmative action is not needed, justified or constitutional, specifically opposing consideration of race in college admissions.

These aren’t the first lawsuits against affirmative action. Since the 1970s, various states have moved to prohibit the consideration of race in admissions, with some cases reaching the Supreme Court. Although the court has historically upheld affirmative action policies in college admissions, there have been times where it ruled to limited them. For example, schools can’t use quotas setting aside a particular number of applicants of color or formulas giving a mathematical advantage to all students applying from a certain racial or ethnic background.

These latest cases don’t present new arguments, but there is an important difference: the Supreme Court is now the most conservative it has been since the 1930s, with a 6-3 majority. Consequently, the widely held opinion is that the court will likely end race-conscious admissions or at least further limit them. It already heard oral arguments last October for these upcoming cases for which the conservative justices expressed skepticism of this practice.

This left many with several questions: What will happen if the Supreme Court ends race-conscious admissions? What will the impact be on higher education? Will this decision apply to other affirmative action policies in employment, government contracting and housing?

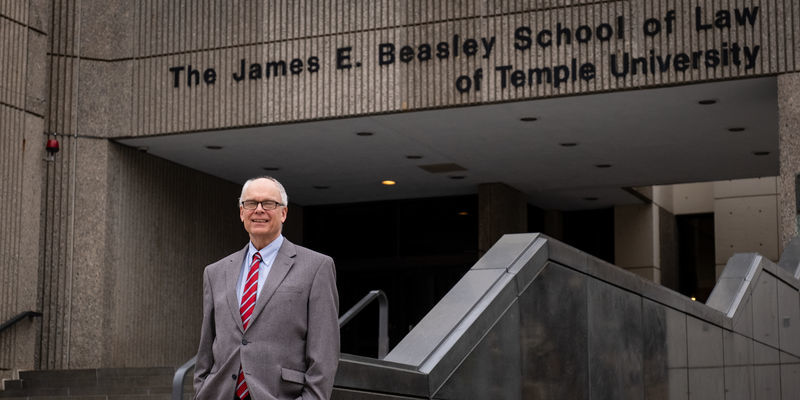

Temple law experts Donald Harris, Timothy Welbeck and Zamir Ben-Dan explain the history of affirmative action and past and current lawsuits challenging this effort as well as the implications of its potential ending.

Key takeaways

- Two new lawsuits are challenging affirmative action, specifically race-conscious admissions at Harvard University and the University of North Carolina.

- Donald P. Harris, associate dean for academic affairs at Beasley School of Law: A narrow ruling by the Supreme Court could be limited to the specific programs at the University of North Carolina and Harvard (and undergraduate programs in general). A broader ruling, however, could have far-reaching impacts, such as prohibiting consideration of race not only in higher institutions’ admissions (graduate school and professional school) policies, but in other policy areas such as housing, government contracting and employment.

- Timothy Welbeck, associate professor of Africology and African American studies, civil rights attorney, and director for Temple University’s Center for Anti-Racism: By putting affirmative action into law, the federal government acknowledged that for centuries it disenfranchised people of color, and particularly in higher education there was a need to establish policies to correct that. But over time these policies were defanged. We haven’t fully succeeded in our efforts to correct two and a half centuries of history.

- Zamir Ben-Dan, assistant professor of law at the Beasley School of Law: Stopping discrimination is the first step. But then measures need to be taken to actually bring about equality is what needs to happen. Otherwise, you have a person who’s 100 years behind another person in a race, and they’ll never catch up. Social inequality is insufficient without economic equality.

What is affirmative action?

In the United States, affirmative action is an effort to improve educational and employment opportunities for underrepresented groups including people of color and women. In other words, affirmative action was initially designed as a policy to level the playing field for historically disadvantaged individuals based on race, color, religion, sex and national origin. More recently, it has expanded to gender representation, people with disabilities and covered veterans. Affirmative action works by the government implementing policies such as grants, scholarships and hiring quotas, among other practices.

How did affirmative action begin?

Affirmative action originated from Executive Order 10925 issued by President John F. Kennedy in 1961. This order included a provision directing all government contractors to take affirmative action to ensure equal opportunity in employment. In 1965 President Lyndon B. Johnson furthered this initiative with Executive Order 11246, which prohibited employment discrimination based on race, color, religion and national origin by organizations with federal contracts and subcontracts. Under this executive order, affirmative action regulations apply to private companies as well. The federal government also instituted these policies under the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Affirmative action was extended to higher education as colleges and universities began to admit more students of color as part of a broader social reform movement in the 1960s and 1970s. These institutions shifted to race-conscious admissions, which consider race as one factor among many, to achieve greater diversity. In response, some states banned this practice, citing reverse discrimination—the idea that members of a majority or historically advantaged group are discriminated against based on protected characteristics such as race, gender and age, among other factors.

In 1996, California passed Proposition 209, which barred discrimination and preferential treatment based on race, sex, color, ethnicity and national origin in public education, employment and contracting. Eight other states followed suit in legally opposing these policies: Arizona, Florida, Idaho, Michigan, Nebraska, New Hampshire, Oklahoma and Washington. Consequently, the enrollment of students of color dropped dramatically in each state. Some cases went to the Supreme Court, setting the stage for the upcoming cases it will hear in June.

“All efforts to address racial oppression and racism are met with equally forceful measures and tactics to keep things the way they are,” said Donald Harris, associate dean for academic affairs at Beasley School of Law.

“Those who profess to be against affirmative action but in favor of racial equality, if that’s even possible, say they’re for equal opportunity, but if one person starts a race 300 years after another and you allow both of them to keep racing then you’re never going to have equal opportunity, so actions have to be taken so that the one who was behind can catch up,” added Zamir Ben-Dan, assistant professor of law at the Beasley School of Law.

Is affirmative action ethical?

Proponents of affirmative action contend that this policy is necessary to provide opportunities to groups who may not otherwise have them or who have come from communities historically denied these opportunities. They also acknowledge that more diversity can be achieved, especially given the low levels of diversity in positions of authority and the lack of recognition for underrepresented groups’ accomplishments.

Meanwhile, opponents argue that affirmative action doesn’t work, saying it hasn’t significantly changed the status quo. Some Americans believe opportunities should be based on merit. These individuals also believe that preferential treatment results in resentment and distrust and disrupts what they perceive as fair play and equal treatment. Opponents of affirmative action tend to argue that we should treat each person as an individual, making no racial distinctions. In the case of race-conscious admissions, they think it hurts students because it results in reverse discrimination.

“A policy like affirmative action is trying to correct some of the horrors of the past,” said Timothy Welbeck, associate professor of Africology and African American studies, civil rights attorney, and director for Temple University’s Center for Anti-Racism. “It was never about taking unqualified Black applicants and supplanting them for qualified white applicants. It was about giving meaningful opportunity to those who had been denied in historic, systemic and structural ways and restoring some semblance of balance that had been denied from the very beginning.”

What other affirmative action cases have gone to the Supreme Court?

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke in 1978 was a landmark case in which the court ruled in favor of affirmative action policies in admissions. Allan Bakke sued the University of California, Davis, after he was rejected twice from its medical school, claiming that setting aside 16 seats for minority students in a class of 100 was discriminatory against him as a white man. It’s worth noting that he was rejected from 12 medical schools but only sued this one with the set-aside program. Even though the court ruled in Bakke’s favor and had him admitted, it also allowed race to be considered as an admissions factor in the overall determination of an applicant.

Additionally, two companion cases reached the Supreme Court in 2003: Grutter v. Bollinger and Gratz v. Bollinger. In the former, Barbara Grutter sued the University of Michigan Law School for discrimination, arguing that its policies granted certain minority applicants a significantly greater chance of admission. The court’s 5-4 decision was that the law school’s admission policy wasn’t illegal, allowing race-conscious admissions to continue. Conversely, in the latter case, the court ruled in favor of Jennifer Gratz, a white woman denied undergraduate admission at the university, agreeing that its admission system relied too much on race. Gratz played a role in Michigan passing Proposal 2, ending race-based preferences in admissions at state universities.

More recently, Fisher v. University of Texas reached the Supreme Court in 2013 and 2016. The university had a program in which applicants graduating in the top 10% of their high school class in Texas received automatic admission. Abigail Fisher, a white woman who was just shy of meeting that quota, argued that the policy discriminated against her based on race, violating the Constitution. Because the first case was inconclusive, the court heard this argument again three years later, narrowly ruling to uphold the university’s affirmative action policy. Now Fisher is one of the leaders of Students for Fair Admissions, the plaintiff in both upcoming Supreme Court affirmative action cases.

What are the new affirmative action cases going to the Supreme Court?

The two latest affirmative action cases to be heard by the Supreme Court in June are Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. President and Fellows of Harvard College and Students for Fair Admissions Inc. v. University of North Carolina.

The Harvard case alleges that the university’s admissions process violates Title VI of the Civil Rights Act, particularly claiming that Asian Americans are disenfranchised or disadvantaged because the admissions practices hold them to a higher standard. The University of North Carolina case argues that the university uses race as a plus factor, meaning race is given too much weight during the admissions consideration, and has not sufficiently considered race-neutral policies that could achieve diversity. Students for Fair Admissions argues the policy violates the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment.

Students for Fair Admissions is proposing to replace affirmative action with class-conscious admissions. The organization believes class-conscious admissions would allow schools to achieve a diverse student body and benefit disadvantaged students without considering race. But Harris, Ben-Dan and Welbeck note that class isn’t the same as race and wouldn’t render the same results.

“Race has been pitted against wealth and economic opportunities,” said Harris. “It’s a matter of preference. There’s still white preference and privilege. Economics can’t capture race.”

A recent report from the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University found that enrollment of minority groups at selective colleges and universities would likely stall or decrease if the Supreme Court bans the consideration of race in admissions, even if other factors, such as class, were weighed more heavily.

In October, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments for these two latest cases, with conservative judges expressing skepticism over both universities’ race-conscious admissions policies. It will announce its final decision in June.

Will the Supreme Court end affirmative action?

Although the Supreme Court is expected to invalidate both universities’ policies and end race-conscious admissions, there are other possible scenarios.

One possible outcome is that the Supreme Court upholds the law and continues allowing race-conscious admissions.

Another outcome would be that the Supreme Court upholds Harvard’s program but invalidates the University of North Carolina’s because its affirmative action violates the 14th Amendment. Or it could deem the University of North Carolina’s policy constitutional but strike down Harvard’s based on a Title VI violation. It could also invalidate both universities’ programs but still protect race-conscious admissions more broadly.

Harris, Ben-Dan and Welbeck agree that the Supreme Court will likely deem Harvard and UNC’s programs unconstitutional and eliminate race-conscious admissions in higher education.

“The decision could be limited to just affirmative action policies in higher education or affirmative action altogether to also include employment and government contracting,” explained Harris. “We could even get down to proxies for race. Are geographic area and socioeconomic status also under attack or at least potentially under attack?”

Although the most likely scenario is that the Supreme Court ends race-conscious admissions in higher education and perhaps affirmative action overall, Welbeck emphasizes that this battle isn’t over.

“Right now, the obstacles in front of us seem insurmountable, particularly looking at the composition of the court and how long the judges will be sitting on the bench,” he said. “It seems we’ve been outmaneuvered. It then becomes incumbent upon us to deepen our resolve to continue the fight that’s ahead. For me, what that means is leading the Center for Anti-Racism and taking up the fight in courts as well as teaching and advocating and encouraging others to do the same. We should take strength from the past and let that inspire the work we’re doing presently.”

Wrap-up

Given its conservative majority, the Supreme Court is widely expected to remove race-conscious admissions at higher education institutions. This ruling could extend to other affirmative action policies, prohibiting race consideration in additional areas such as employment, housing and government contracting. Harris, Welbeck and Ben-Dan agree that although this challenge to affirmative action isn’t new, the court appears willing this time to overturn precedent.