Clearing the fog

Researcher gets $1.5 million grant to examine side effect of chemotherapy

| Many of the side effects from chemotherapy are well documented: fatigue, nausea and hair and weight loss. But the medical community is divided on whether one lesser-known effect even exists. It's called chemotherapy-induced cognitive deficits, or “chemo fog,” and pharmacologist Ellen Walker hopes her research not only proves it’s real, but finds the cause.

Walker, a Ph.D. and associate professor of pharmacodynamics at the School of Pharmacy, received a $1.5 million National Institutes of Health grant at the beginning of this year to study the possible effects of drugs used during chemotherapy on cognitive impairment. It’s a big grant, with perhaps even bigger implications for how researchers and patients deal with chemotherapy-induced cognitive deficits. Chemotherapy patients liken the effect to being in a fog, as if their brain isn’t working right. Following treatment, they often misplace items, have difficulty multi-tasking and lose short-term memory. And while there is clinical evidence to support its existence, research studies on the topic are scant. |

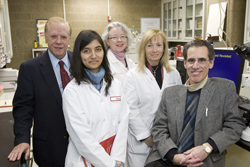

Photo by Joseph V. Labolito/Temple University

The chemo fog research team: (From left) Ronald Tallarida, Ph.D., performs analysis of drug combination data and synergy effects; Swati Nagar, Ph.D., pharmacokinetics expert who translates human drug regimens to mice doses; Ellen Walker, Ph.D., principal investigator, psychologist and pharmacologist who designs and carries out the experiments; Rachel Clark-Vetri, Pharm.D., oncology pharmacist who chooses which drugs to use; and Bob Raffa, Ph.D., pharmacologist who acts as the interface between the clinical and preclinical literature and will help analyze results and synergy effects.

|

|

|

|

|

“My colleague Bob Raffa and I were stunned at the lack of published literature, considering cancer patients have been getting chemotherapy for nearly 50 years,” said Walker. “Most studies have looked at how well chemotherapeutic agents kill the tumor, not if they cause a cognitive deficiency, like memory loss.” Walker and Raffa decided to fill that void. Two years ago, Walker and Pharm.D. student John Foley set out to see if certain chemotherapeutic agents caused memory and learning deficits. They tested two older drugs commonly used to treat breast cancer, a cancer with recently higher survival rates whose survivors have dominated the limited clinical research on chemotherapy-induced cognitive deficits. They suspected the drugs, methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil, weren’t toxic alone, but when given together, could cause deficits. Six months into their research, their hunch proved right. “Alone, methotrexate didn’t cause learning or recall deficits when given once,” said Walker. “Giving 5-fluorouracil once showed some deficits in recall, but giving both drugs together had a synergistically worse effect on the ability to learn and remember in preclinical trials.” In other words, the interaction of the drugs caused a greater impairment when given in combination than when given individually. And as Walker expanded their research, giving the drugs once a week for three weeks, they saw even more deficits than just giving it in shorter increments. Armed with their results, which were published in the May 2008 issue of the Journal of Psychopharmacology, this one-time side project became a priority. The study was followed by months of research and the involvement of more colleagues to help define better dose combinations and regimens. But there was also the ping-pong of NIH reviews and revisions to endure and Walker and her research team had run out of money. In March 2008, a $50,000 bridge grant through Temple’s Office of Research and Strategic Initiatives allowed her research to continue. “I had to look at the score twice because I couldn’t believe it,” said Walker. Walker wasn’t the only one impressed by the score. “I was delighted to learn about the grant and its truly outstanding ranking,” said Larry F. Lemanski, Ph.D., senior vice president for research and strategic initiatives at Temple. “This major grant from the National Institutes of Health will allow Dr. Walker to significantly expand her research programs. At the same time, the award will increase Temple’s reputation as a major player in this very important field of biomedical research.” Indeed, the funding will allow Walker to triple her efforts. She can dedicate a staff member full time on the project and study four more chemotherapeutic agents. And down the road, she would like to figure out how to protect the brain before chemotherapy to prevent chemo fog. For now, chemo fog is still mired in controversy, as clinicians and scientists debate if the disease itself or the drugs to fight cancer cause it. Other culprits could include genetics, hormone inhibitors, anemia and early-onset menopause. Chemotherapy often catapults women into menopause, potentially leaving them fuzzy-minded. And there are those who doubt chemo fog is real. Walker believes it is. She recalls how, while battling breast cancer, her mother put a chicken still covered in plastic wrapping in the oven for dinner. “It seemed like she wasn’t always thinking clearly even after her chemotherapy was over,” she said. “I always wondered whether it was the psychological stress of cancer, the chemotherapy, or some other side effect of the many medications she received.” Ellen Walker may well be on her way to finding the answer. |