|

workers against the smallpox virus, which theoretically could be used in a bioterror attack,” said lead researcher Sarah Bass, Ph.D., M.P.H., assistant professor of public health at Temple’s College of Health Professions. “But it was left to each state to run the program, and each did so differently. As a result, less than 40,000 ER workers nationwide were vaccinated.”

Bass noted that study participants were reluctant to get this particular vaccine because it is a live form of the virus and they weren’t sure of the effects it would have on their health, if they could spread it to others, or if it would mean missed time from work.

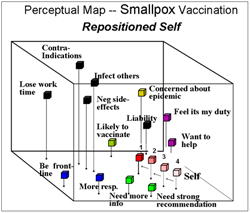

Using a unique method called “perceptual mapping,” researchers found that today, with no threat of an attack, ER workers would only be inclined to get vaccinated if they first got a recommendation from a trusted source, such as another hospital or healthcare professional. But when the threat of an outbreak was imminent, participants said they felt it would be their duty to get vaccinated, with or without a recommendation.

“States that crafted messages around the endorsement of a trusted source were able to get more healthcare workers vaccinated,” Bass said. “But we see that the message needs to shift if an outbreak is imminent: that workers need the vaccination to stay healthy and alive.”

For this study, the researchers first asked 73 emergency room workers at hospitals in the Philadelphia area to rate on a scale of 1–10 the importance of various aspects of the smallpox vaccination in four separate scenarios: Today, with no smallpox outbreak4;

if another terrorist attack happened in the United

States³; if a smallpox outbreak occurred somewhere in the United States²; and if a smallpox outbreak occurred in the Philadelphia area¹.

Data from the surveys was then used to create the perceptual maps, three-dimensional models of respondents’ attitudes, toward getting vaccinated. This technique is often used by marketers and politicians to determine whether a consumer will buy a product or vote for a candidate. For this study, researchers were able to see significant shifts in attitude under increasingly higher levels of threat.

“This data will help public health officials craft effective messages according to specific scenarios. These messages can then be used in preparation for an outbreak, so in case it does happen, we won’t be caught off guard,” Bass said. “More importantly, these results have serious implications for how messages are crafted in the event a pandemic such as avian flu or SARS occurs. The circumstances under which these events occur dictate how to address the concerns of healthcare workers or the general public.”

Read the study.

*****

Other authors on this study include Thomas Gordon, Ph.D., and Sheryl Ruzek, Ph.D., M.P.H., professors of public health at Temple University, and Alice Hausman, Ph.D., M.P.H., director of the Center for Preparedness Research, Education and Practice and professor of public health at Temple University.

This research was funded in part under an agreement with the Pennsylvania Department of Community and Economic Development and the Pennsylvania Department of Health, in coordination with the CDCP Cooperative Agreement on Public Health Preparedness and Response for Bioterrorism. The funding agencies specifically disclaim responsibility for any analyses, interpretations or conclusions.

|