Historian’s new book considers America’s all-volunteer Army

| CONTACT: Kim Fischer <kim.fischer@temple.edu>> 215-204-1092 |

As President Barack Obama announces his new blueprint for the war in Afghanistan, which includes an increase of up to 30,000 U.S. troops, it can be easy to take for granted that those troops come from an all-volunteer force. As President Barack Obama announces his new blueprint for the war in Afghanistan, which includes an increase of up to 30,000 U.S. troops, it can be easy to take for granted that those troops come from an all-volunteer force.

It has been a full 37 years since President Nixon fulfilled his campaign promise and ended the draft in 1973, shortly after the last American combat troops returned from Vietnam. In America’s Army: Making the All-Volunteer Force, Temple historian Beth Bailey tells the story of America’s all-volunteer force (AVF) and in the process offers a history of America in the post Vietnam era. According to Bailey, the Army — more so than other institutions — has had to directly confront the legacies of the social change movements of the 1960’s. At first glance, it might seem like a stretch for Bailey, a social and cultural historian, to tackle a military topic. Her last book, Sex in the Heartland: Politics, Culture, and the Sexual Revolution (Harvard University Press, 1999) argued that the sexual revolution was forged in towns and cities alike, as “ordinary” people struggled over the boundaries of public and private sexual behavior in postwar America. But, explained Bailey, “I have always been interested in the question of who belongs, of who counts in American society and on what terms. Military service is one of ways that people claim the full rights of citizenship in this country.” For the Army, the move to the all-volunteer force was a move to the market, said Bailey. |

|

|

Click the images below for a larger preview

Click the images above for a larger preview

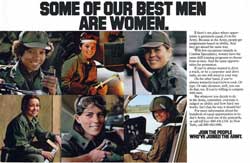

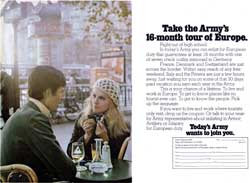

From the beginning of the transition from the draft to an all-volunteer force, the army recognized the importance of advertising. The new recruiting ads were designed to emphasize the many opportunities of army life and offer the promise equal opportunity.

|

According to Bailey, the Army used sophisticated advertising campaigns to portray military service as an opportunity rather than as an obligation. “The first campaign turned the classic Uncle Sam ‘I Want You’ recruiting slogan upside down, telling young people ‘Today’s Army Wants to Join You,’” said Bailey. As the Army succeeded in turning an obligation into an opportunity, it had to contend with the people it attracted. “When women began to volunteer, the Army had to grapple with questions about what women can do and what women should do,” she said. Similarly, at the same time that huge racial divisions existed across the country, African Americans started joining the Army in significant numbers. “So, the Army had to figure out ‘how this will work.’ They turned to race-conscious promotion and leadership policies.” |

|

Today, the extended war in Iraq highlights unforeseen demographic changes brought by an all-volunteer force, said Bailey. In the early years of the AVF, Americans worried about the overrepresentation of members of minority groups or the growing number of women, but few anticipated that the shift to volunteer status would produce a family-oriented army. In fact, volunteer soldiers today are older, more are married and more have children than those in the draft-based Army. And repeated deployments are very hard on their families |

|