Pharmacy students gaining research edge

New grant funds students in the lab

Photo

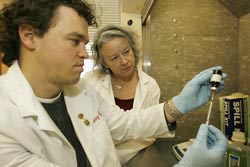

Ryan S. Brandenberg/Temple University Pharmacy student John Foley, (left), assists Dr. Ellen Walker in her research lab.

|

“Dazzled” by how a little pill could make such a big difference, Cristina Santos decided to study how drugs work when she was still in high school. Today, Santos, who received her PharmD from the School of Pharmacy in 2005, is pursuing a doctorate in pharmaceutical sciences at the University of North Carolina. She’s the first Temple Pharm.D. to go on to a Ph.D. program.

Not wanting “just a job,” John Foley was searching for a career.

|

|

Once in pharmacy school, Foley, who held an undergraduate degree in history and theology, wanted to avail himself of every opportunity and took a job working one day a week in Temple Professor Ellen Walker’s research lab.

Santos and Foley reflect a growing trend at the School of Pharmacy whereby students, who traditionally have pursued a patient-oriented course of study, are now adding basic science research to the mix. They want both, and it’s opening even more doors in a field already rich in career opportunities.

|

|

|

Half of the student researchers at the School of Pharmacy work in professor Scott Rawls’ lab, thanks to the support of a new three-year, $225,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health to train non-traditional students, such as Pharm.D.s, to do research.

|

Photo Ryan S. Brandenberg/Temple University

Dr. Scott Rawls (left), whose lab investigates the role of glutamate systems in opioid and psychostimulant addiction, has 12 pharmacy students working on several projects.

|

|

Those graduates who can offer both a clinical and a scientific research background are in big demand in industry and academia. The buzz word for this combination of skills is translational research: work that translates from the lab bench to the patient bedside. The goal, according to the NIH — which is focusing its funding on translational research — is to catalyze the application of new knowledge and new treatments in real-life patients.

|

|