Your teachers may have told you not to copy your neighbor's work. But it turns out that imitation plays a crucial role in the development of cognitive and social communication behaviors.

And, for babies, imitation is the foremost tool for learning As renowned people-watchers, babies often observe others demonstrate how to do things and then copy those movements. It's how little ones know, usually without explicit instructions, to hold a toy phone to the ear or guide a spoon to the mouth.

Now researchers from Temple University and the University of Washington have found the first evidence revealing a key aspect of the brain processing that allows babies to learn through observation.

The findings, published in PLOS ONE, are the first to show that babies' brains showed specific activation patterns when they observed an adult performing a task with a specific part of her body, such as her hand or foot.

When 14-month-old babies quietly watched an adult use her hand to touch a toy, the hand area of the baby's brain lit up. When another group of infants watched an adult touch the toy using only her foot, the foot area of the babies' brains showed more activity.

"The reason this is exciting is that it gives insight into a crucial aspect of imitation," said co-author Peter Marshall, associate professor of psychology at Temple. "To imitate the action of another person, babies first need to register what body part the other person used. Our findings suggest that babies do this in a particular way by mapping the actions of the other person onto their own body."

The study took advantage of how the brain is organized. The sensory and motor area of the cortex, the outer portion of the brain known for its creased appearance, is arranged by body part with each area of the body represented in identifiable neural real estate. Prick your finger, stick out your tongue, or kick a ball and distinct areas of the brain light up according to a "somatotopic map."

"Our findings show that when babies see others produce actions with a particular body part, their brains are activated in a corresponding way," said Joni Saby, lead author and a psychology graduate student at Temple. "This mapping may facilitate imitation and could play a role in the baby's ability to then produce the same actions themselves."

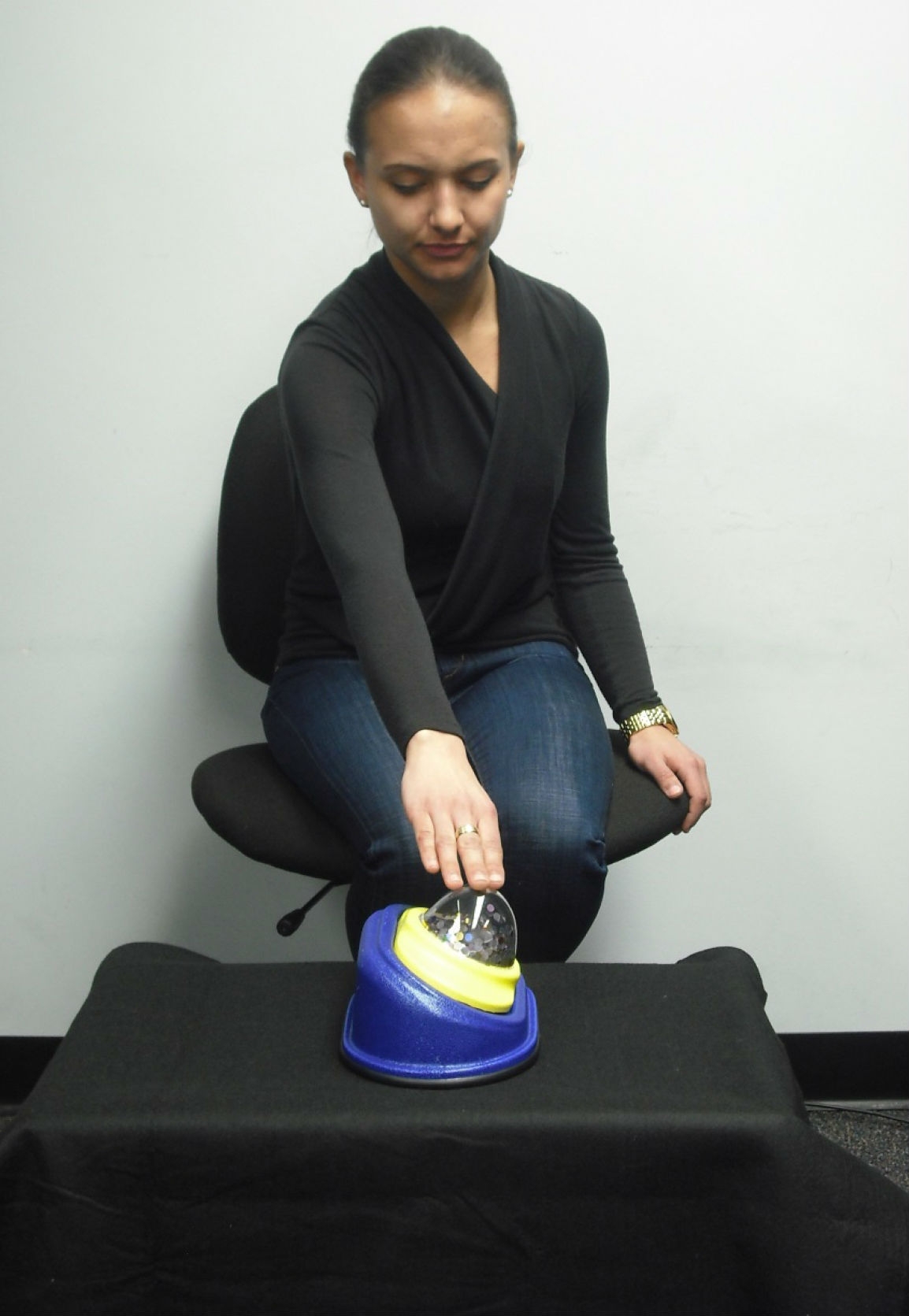

The 70 infants in the study, conducted in the Developmental Science Lab at Temple, wore electroencephalogram, or EEG, caps with embedded sensors that detected brain activity in the regions of the cortex that respond to movement or touch of the feet and hands. Sitting quietly on a parent's lap, each baby watched as an experimenter touched a toy placed on a low table between the baby and the experimenter.

The toy had a clear plastic dome and was mounted on a sturdy base. When the experimenter pressed the dome with her hand or foot, music played and confetti in the dome spun. The experimenter repeated the action – taking breaks after every four presses – until the baby lost interest.

"In psychology one of the big questions is how to relate behavior to processes in our brains," said Marshall. "With this study, we have opened a window into how our brains help us learn and relate to one another."

"Babies' brains are wired to connect them to other people. This connection is a key aspect of social awareness and bonding," he said.

The study was funded by The National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.