Chronic sleep disturbance might trigger onset of Alzheimer’s

People who experience chronic sleep disturbances might face an earlier onset of dementia and Alzheimer’s, according to a new preclinical study by researchers at Temple University.

“The big biological question that we tried to address in this study is whether sleep disturbance is a risk factor in developing Alzheimer’s or something that manifests with the disease,” said Domenico Praticò, professor of pharmacology and microbiology/immunology in Temple’s School of Medicine, who led the study.

Initially, the researchers looked at longitudinal studies that indicated that people who reported chronic sleep disturbances often developed Alzheimer’s disease.

They used a transgenic Alzheimer’s mouse model that begins developing memory and learning impairment at about 1 year of age—the equivalent of a human in his or her mid-50s or -60s. At 14 to 15 months, it begins to have the typical human brain pathology of Alzheimer’s, including amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles, the two major brain lesion signatures for that disease.

The eight-week study began when the mice were approximately 6 months old. One group was kept on a schedule of 12 hours of light and 12 hours of darkness. A second group was subjected to 20 hours of light and only four hours of darkness.

“At the end of the eight weeks, we didn’t initially observe anything that was obviously different between the two groups,” Praticὸ said. “However, when we tested the mice for memory, the group that had the reduced sleep demonstrated significant impairment in its working and retention memory, as well as its learning ability.”

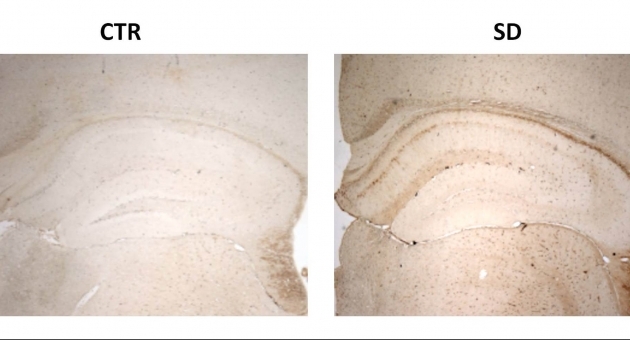

The researchers then examined the mice’s brains to look at aspects of the Alzheimer’s pathology—mainly, the amyloid plaques and tau protein tangles.

“Surprisingly, we didn’t see any difference between the two groups in the amyloid plaques,” Praticὸ noted. “But we did observe that the sleep disturbance group had a significant increase in the amount of tau protein that had too many phosphate group attach themselves and became phosphorylated, forming the tangles inside the brain’s neuronal cells.”

Tau protein is an important component for neuronal-cell health, but elevated levels of phosphorylated tau can disrupt the cells’ synaptic connection—the ability to transport a nutrient or chemical or transmit an electrical signal from one cell to another, Praticò said.

“Because of the tau’s abnormal phosphorylation, the sleep-deprived mice had a huge disruption of this synaptic connection,” he said. “This disruption will eventually impair the brain’s ability for learning, forming new memory and other cognitive functions, and contributes to Alzheimer’s disease.”

Since the sleep-deprived mice developed the Alzheimer’s brain pathology earlier than the mice who were not deprived, sleep disturbance acts as a trigger that accelerates the pathological process of tau becoming phosphorylated and damaging the synaptic connection irreversibly.

“We can conclude from this study that chronic sleep disturbance is an environmental risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease,” he said. “But the good news is that sleep disturbances can be treated easily, which would hopefully reduce the Alzheimer’s risk.”

The researchers published their findings, “Sleep deprivation impairs memory, tau metabolism and synaptic integrity of a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease with plaques and tangles,” in Neurobiology of Aging.

The study was funded in part by the Alzheimer’s Art Quilt Initiative.

NOTE: Copies of this study are available to working journalists and may be obtained by contacting Preston M. Moretz in Temple University Communications at pmoretz@temple.edu.