Five unique ways to experience Philadelphia’s past

As students learn about our one-of-a-kind city, one professor encourages them to explore its most unique historic spaces.

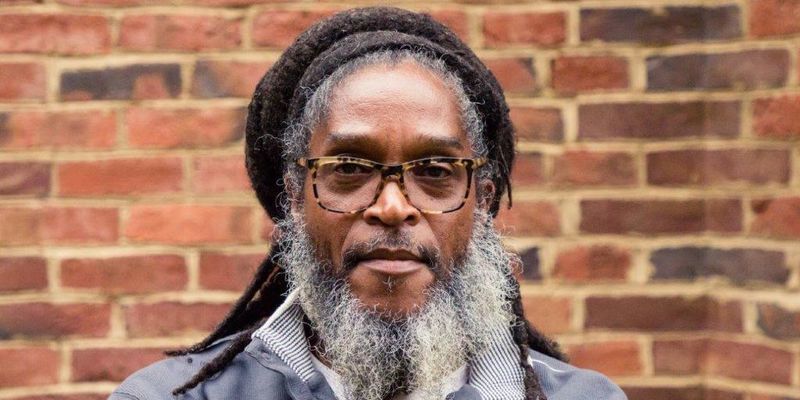

As students explore the historic streets of Philadelphia, one professor is working to remind everyone to venture off the beaten path. According to Seth Bruggeman, associate professor of history and director of the Center for Public History, Temple has been directly involved in preserving and promoting some of our city’s most interesting, lesser known sites, developing creative interpretive programming and unique engagement opportunities for all.

As one of the oldest continuously occupied streets in Philadelphia, Elfreth’s Alley has become one of the most internationally recognized historic places in the U.S. When Ted Maust, CLA ’18, joined the Elfreth’s Alley Museum as associate director in 2019 and later becoming its director, he pushed for the museum to spotlight the stories of labor, race, gender, sexuality and other facets of the American experience that other museums don’t often explore.

“What Maust and his crew have done for Elfreth’s Alley over the last year or so is to reverse the narrative and show us that this is a place where you can discover any story about any kind of person, and those people are probably going to have something in common with you, no matter who you are,” said Bruggeman.

The staff got even more creative despite the limitations of the pandemic, and began a podcast called The Alley Cast. In this program, they cover Elfreth’s Alley’s connections with domestic workers, housing reform/historic preservation, child labor, boarding houses, feminism, and more. People interested in supporting this unique museum can make a plan to visit or join a discussion about the podcast on social media.

A little further north in Germantown sits the historic Stenton House, where recent preservation efforts have been dedicated to a former enslaved woman named Dinah. Bruggeman’s students have helped this museum in its research efforts to study the existing monument to Dinah, the message it conveys, the reasoning behind its creation and what historic biases its current format feeds into.

“My students were aware that the Dinah marker sat in uneasy juxtaposition with honoring her memory and normalizing the enslavement of Black people,” said Bruggeman. “Stenton used our research to help them brainstorm how to revisit the story of Dinah and do some preliminary exhibition development.”

At the conclusion of this research effort, Bruggeman’s students helped the museum develop ways to honor Dinah’s memory with a new monument, which Tyler School of Art and Architecture Professor Karyn Olivier was selected to design. Those interested can view Stenton’s other preservation efforts with regard to Dinah by watching the “Remember My Name” virtual program or by making a plan to visit the museum.

The Independence Seaport Museum sits on the Delaware River’s waterfront and treats visitors to broad sensory encounters where history meets natural resources. Visitors can enjoy a variety of in-depth experiences including a tour of the Cruiser Olympia, the oldest steel floating warship in the world. Craig Burns, TYL ’94, the chief curator of the museum, has been working with Bruggeman to tell the more complex international story of Olympia’s past.

“I love the Olympia because it’s amazing to see, but it’s also such a powerful and dangerous object that it really demands we rethink how we teach history,” said Bruggeman.

While the battleship and Submarine Becuna attract considerable attention, the Independence Seaport Museum distinguishes itself with its unique Workshop on the Water and River Alive programs. Emphasizing the science and ecology of water systems, the museum demonstrates how waterways connect communities in unexpected ways. Those interested in visiting can purchase tickets ahead of time and plan for the exhibits they want to see.

People are often shocked to learn that a branch of the National Archives (NARA) exists in Philadelphia. Temple alumnus Grace Schultz, CLA ’14, ’16, who works there as a professional archivist, said patrons comprise more than just historians. They include genealogists curious about their family trees, veterans who are interested in accessing records of their service, environmental agencies seeking information about superfund sites, immigrants who are looking for naturalization records, and many more.

“You don’t need a special license or authorization to go to an archive and experience any number of fascinating documents,” said Bruggeman. “This misconception that archives are off-limits is something we public historians want to change. We want to empower our neighbors to make sense of their own stories, and NARA can help them do that.”

NARA has been working with interns from Temple on projects designed to contextualize difficult and complex historical topics such as how the Chinese Exclusion Act impacted the racism within living exhibits in the late 1800s. Before COVID-19, anyone could visit the facility without an appointment to conduct family or historical research. Though the facility is presently closed to the public with limited appointments for researchers, many of the documents are digitized and may be accessed online.

The last place Bruggeman recommends visiting exists on Temple’s own campus: the Special Collections Research Center (SCRC), which acts as a caretaker and repository for rare materials including historical photographs, newspaper clippings, organization archives, newsreel footage, publications and more. One of the frequently used resources is the Urban Archives Collection, which Bruggeman said helps urban historians conceptualize Philadelphia’s history.

“The SCRC does many things to try bringing attention to the public about its resources,” said Bruggeman. “There’s a project called Civil Rights in a Northern City, which is designed to share its digitized materials with a wider audience.”

This fall, Bruggeman’s graduate students will be using the material at the SCRC to create an online campus memory map. The SCRC’s resources are open to the public, though many materials are housed off-site and require two business days’ notice to retrieve them. A portion of the assets are digitized and are publicly accessible without a Temple account.

As students spend time familiarizing themselves with Philadelphia, Bruggeman encourages them to seek out the historical impact of unexpected places. When people learn that the old building used for a wedding reception turns out to have housed the first Black fire company, and when the empty storefront near the neighborhood dentist’s office is discovered to be the home of “The Sound of Philadelphia,” residents and visitors alike have a greater chance of connecting with the history of this city.

“People should think of Philadelphia as itself a living museum, and imagine what it would be like if preservation had always been equitable,” he said.

—Rayna Lewis