Grad student preserves stories of African-American AIDS activists through oral history project

For many in the U.S., the face of the AIDS epidemic is a gay, white man, an image seen often on television and in movies. And for just as many, when we envision an AIDS activist, we likewise picture a gay, white man.

"That's the stereotype, but it's not the whole picture," said Temple doctoral candidate Dan Royles.

Since the beginning of the AIDS epidemic in the U.S., people of color have contracted HIV at a disproportionately high rate. And in response, African-American men and women have worked hard to educate their neighbors about the disease and to alert officials to the severity of the epidemic in black communities.

"But if you look at what has been written about AIDS in America, you would think that the only AIDS activists were white, gay men," said Royles. "It's time to tell the rest of the story."

When Royles began conducting research for his dissertation in history, he was interested in uncovering the strategies that African-American activists used to mobilize their communities to focus on and attend to the AIDS epidemic among black people in the U.S.

However, he quickly learned that documented sources on the topic were lacking. So he set out to find and interview sources on his own.

In the process, he met face to face with those who had served on the frontlines of the epidemic in African-American communities, recording and painstakingly transcribing each interview.

He started his interviews in Philadelphia and, before he knew it, the project had taken on a life of its own.

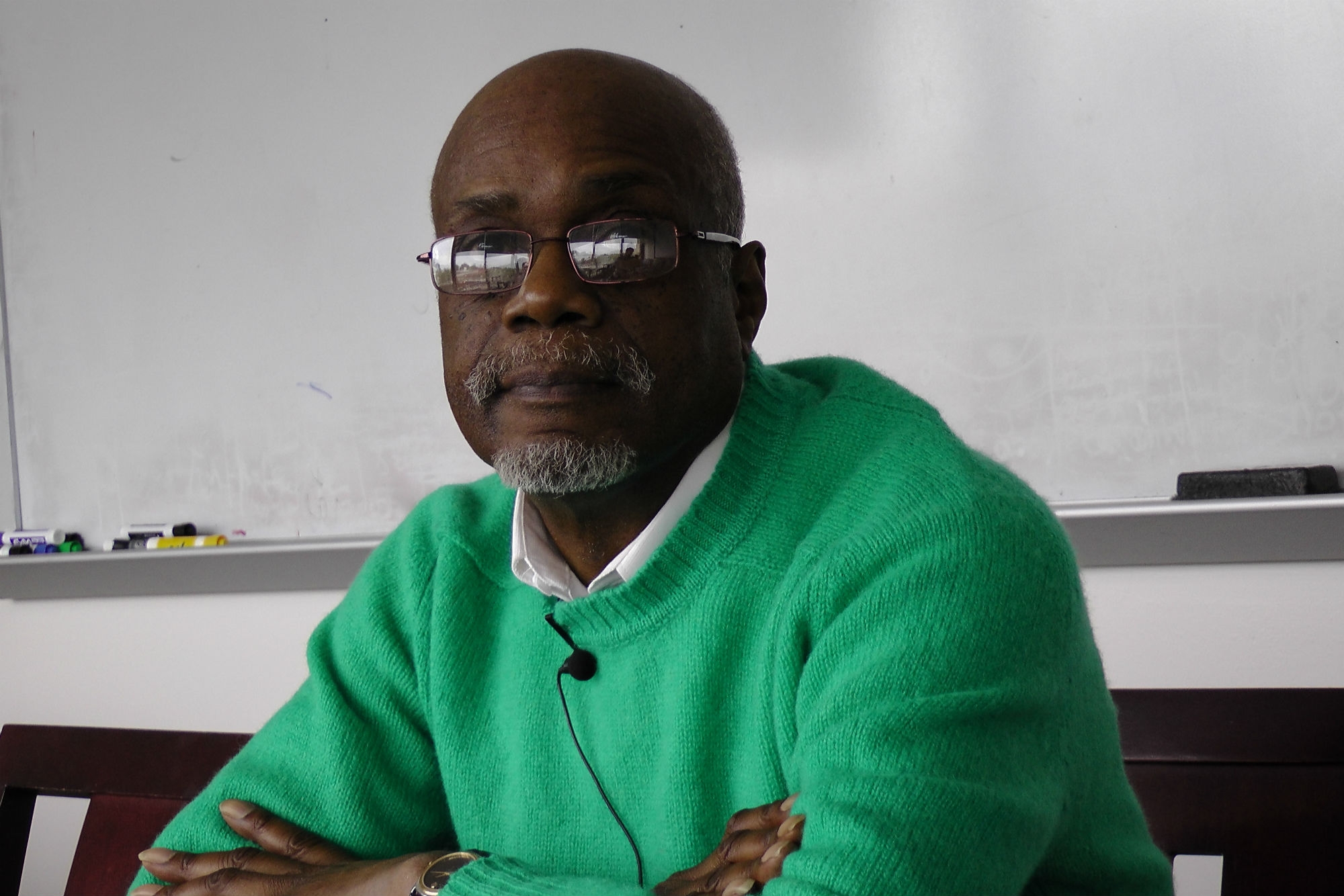

In one interaction, Royles spoke with Curtis Wadlington, who helped found the highly effective education agency Blacks Educating Blacks About Sexual Health Issues (BEBASHI) in Philadelphia in 1985. Wadlington explained how he and other activists achieved success in their communities by linking AIDS to other pressing issues, such as hunger and healthcare reform.

"We founded BEBASHI and we tried to say there's another message besides 'John and his lover Rick,'" Wadlington told Royles.

He also interviewed Pernessa Seele, an immunologist and the CEO and founder of Balm in Gilead, Inc., a religious-based organization that provides support to people with AIDS and their families and works toward prevention of HIV and AIDS.

In 1989, Seele initiated the Harlem Week of Prayer for the Healing of Aids, now a national annual event. "Every week we had an education program in a church or a mosque, always a place of worship. So that's how we got started. Today, all of the awareness days are modeled after the Harlem Week of Prayer for the Healing of Aids."

Each individual interviewed would suggest that he talk to several others. And Royles began to develop a backlog of interviews needing transcription, all the while recognizing the significance of the project he had undertaken. Many of the interviewees had been living for years with HIV.

"We don't have forever to hear the stories of these activists. The need to preserve them now is urgent," said Royles.

To expand the project to other cities and to archive the interviews for the use of future scholars, Royles launched The African American AIDS Activism Oral History Project, which has been successfully funded through a Kickstarter campaign.

Though his dissertation has reached completion, Royles continues to conduct interviews. In May, he visited New York, Philadelphia, Atlanta and Columbia, South Carolina, to talk with top-level public health policymakers, academics, artists, people who work in HIV prevention and a hairdresser who has been distributing condoms and information about HIV from her salon since 1986.

"Those trips were made possible by the Kickstarter campaign, so I'm extremely grateful to my backers for their generosity," said Royles.

He plans to donate transcripts of the interviews to Temple's Paley Library.