In some classes, smartphones are viewed as aid, not barrier, to learning

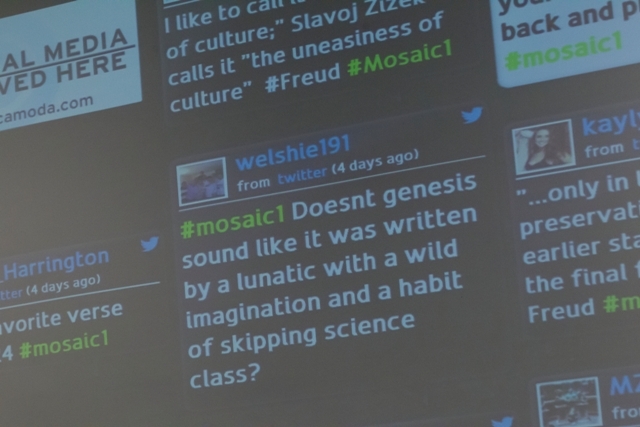

They make you laugh. They make you think. And, sometimes, they just make you shake your head — or “SMH,” in the language of the Twitterverse [shake my head].

The tweets, by Jordan Shapiro and his students in Temple University’s “Mosaic” humanities courses, provide a glimpse at how they are learning about some of the biggest thinkers of the Western academic tradition, such as Freud, Rousseau and Aristotle:

Man this is bleak. I wonder how many parties Freud wasn't invited to? #wetblanket

Feeling that Ares rage right now.

"I to die and you to live; but which of us has the happier prospect is unknown to anyone but God" ...Socrates rules

The Absurdist Bible, written by Samuel Beckett. SPOILERS: God's waiting for Godot.

"Arm yourself for war and put on your strength." #Iliad Strength comes from the armor?

"And on the third day, The Lord created Saturn, and He liked it...and lo, He put a ring on it."

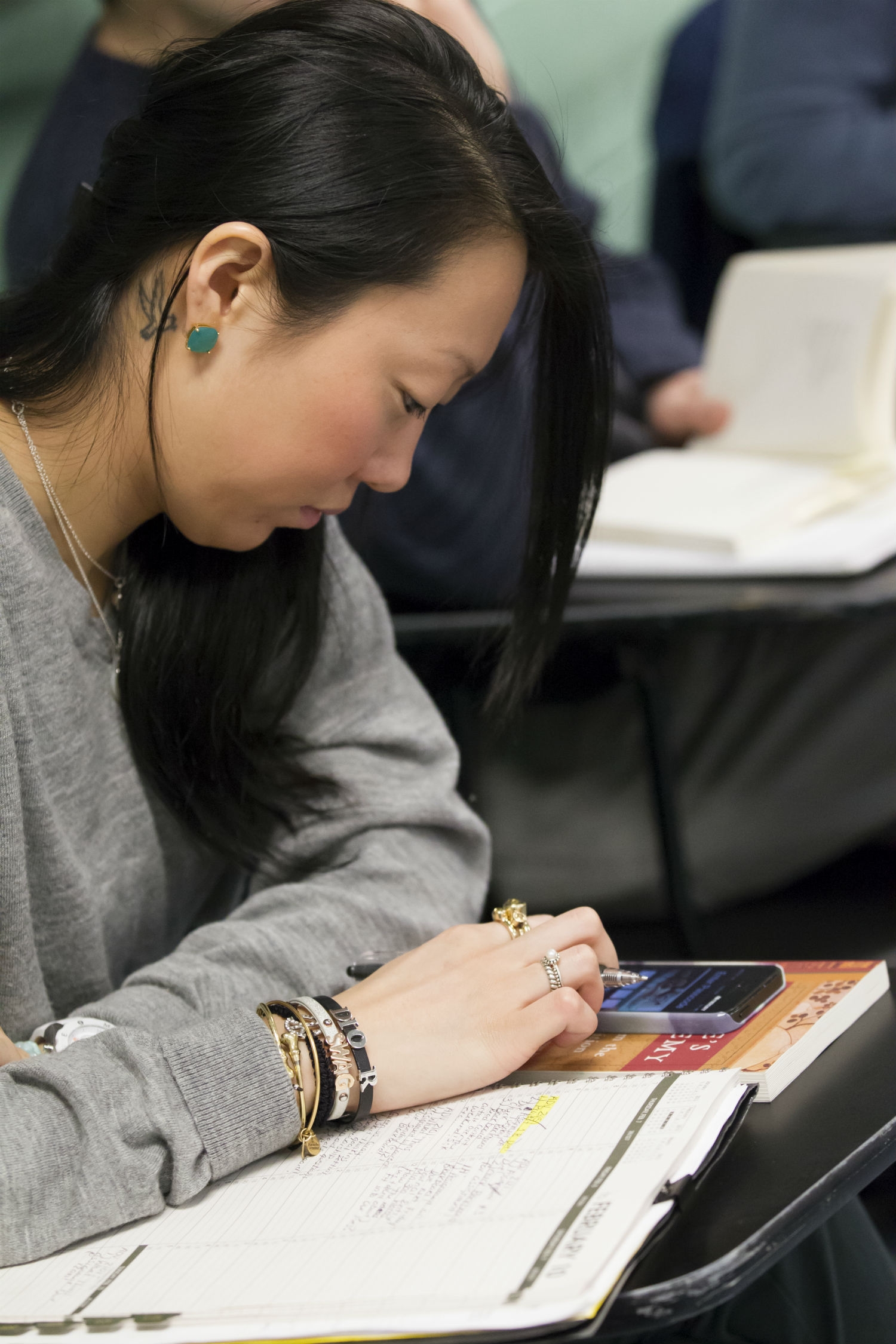

At the beginning of the semester, Shapiro tells the students that cell phones are welcome in class. In fact, he asks them to tweet about what they’re learning both during and after class hours using the hashtags #mosaic1 and #mosaic2. The caveat? They must remain engaged throughout.

“My whole idea is if you’re tweeting about what I’m talking about then I got you,” said Shapiro. “You’re showing me you care.”

College professors have had to reckon with the near ubiquity of smartphones in their classrooms for the past several years. Some prefer to look the other way, while others expressly ban their use, and still others, like Shapiro, integrate them into class. It’s been a hot topic of conversation among professors in Temple’s Intellectual Heritage Program (IH), the home of the “Mosaic” curriculum.

“I see IH instructors testing all kinds of ways to increase inclusion and participation — and testing themselves out in the process,” said Doug Greenfield, associate director of IH. “We talk a lot about accommodating different learning styles; we also need to acknowledge that there are different and equally effective teaching styles. What's key, and what I see in IH, is commitment to dialogue, experimentation and evolution.”

In addition to encouraging student tweeting during class, Shapiro often projects the Twitter stream on a screen so that the whole class can watch the activity. It illustrates, he believes, how students are doubly engaged — in both the live conversation and the Twitter stream.

“Smartphones are a part of their — and my — lived experience, so I try to teach them to use their technologies articulately and intelligently,” said Shapiro. “They will need to be able to navigate the intellectual landscape of the 21st-century workplace, which now includes social media.”

Several of Shapiro’s colleagues in IH have different approaches to cell phones in the classroom, including Noah Shusterman, who has taught at Temple for more than a decade.

“In ‘Mosaic,’ discussion is a fundamental aspect of the class,” he said. “It’s not a class about a collection of facts, but rather being able to assess texts critically and form arguments, so we need to hear from students and they need to hear from each other.”

During class, Shusterman asks that phones are turned off and out of sight.

“Anything that takes attention away from the discussion has a way of affecting the entire class,” he said. “I also want to carve a space in their lives where they can appreciate a class as it’s been taught for many decades.”

Rick Libowitz, a Temple alumnus and associate professor in IH also asks students to keep phones off.

Although Libowitz jokes that he’s a Luddite, he’s not. YouTube is one of his favorite classroom tools.

For Freud’s chapter on dreams, Libowitz plays a YouTube video of the Everly Brothers singing, “All I have to do, is dream.” The lyrics, “I’m dreaming my life away,” are perfect for what Freud is talking about, explains Libowitz.

“What I want to show them is that the answers change, but the questions remain the same, and ultimately the questions are more important than the answers,” he said. “That’s the IH program in essence.”

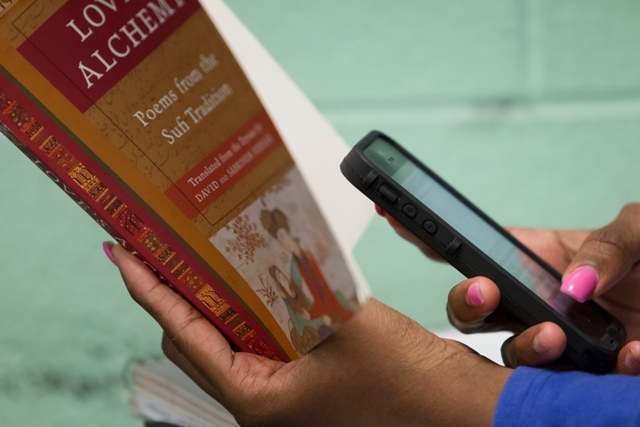

Another longtime IH professor, Susan Bertolino, now allows cell phones for specific projects, after holding a hard line for several years.

“Once I started allowing them in certain circumstances, such as group projects, it helped make the students feel more positive and not feel so disciplined,” she said. “It created more of a sense of community.”

In addition to smartphones and social media, the “Mosaic” courses are venturing online. Last semester, a team that included Shapiro designed and piloted online classes. This spring, IH is piloting hybrid classes, which combine online and in-person classes.