Exploring the history of Juneteenth, a day of celebration and reflection

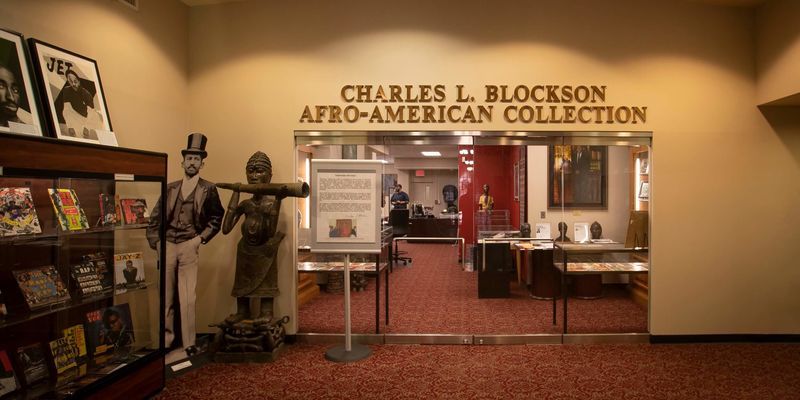

For Diane Turner, curator of the Blockson Collection, Juneteenth is a time to contemplate the impact of slavery on African Americans.

On June 19, 1865, Major General Gordon Granger, an officer in the Union Army, issued an order in Galveston, Texas: “The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free.”

Granger’s order laid the foundations for Juneteenth, the oldest nationally-observed celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the U.S.

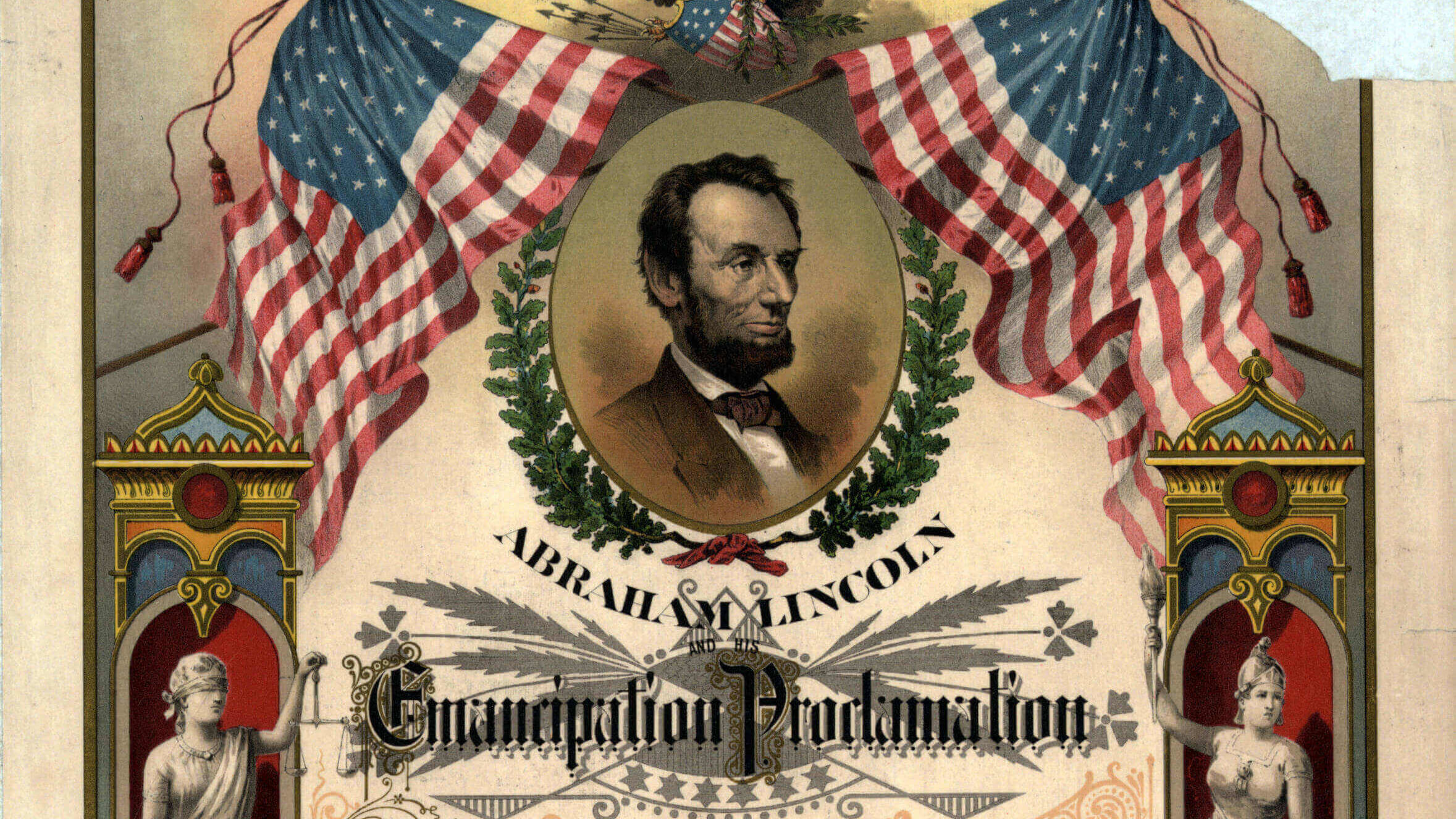

A portmanteau of “June” and “nineteenth,” Juneteenth commemorates the day when enslaved Africans in Texas were told they were free, two and a half years after Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation and nearly six months after the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution passed Congress. The 13th Amendment states, "Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction."

“Juneteenth is a day that is a time to celebrate African American history and culture,” said Diane Turner, curator of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple. “But it’s also a time to reflect directly on the American institution of slavery.”

“It’s a time to look at some challenges in our community,” she said, challenges highlighted by the protests sparked by George Floyd’s death in 2020, and “understand the the legacy of slavery and its impact on Black people, the Black family and the Black community.”

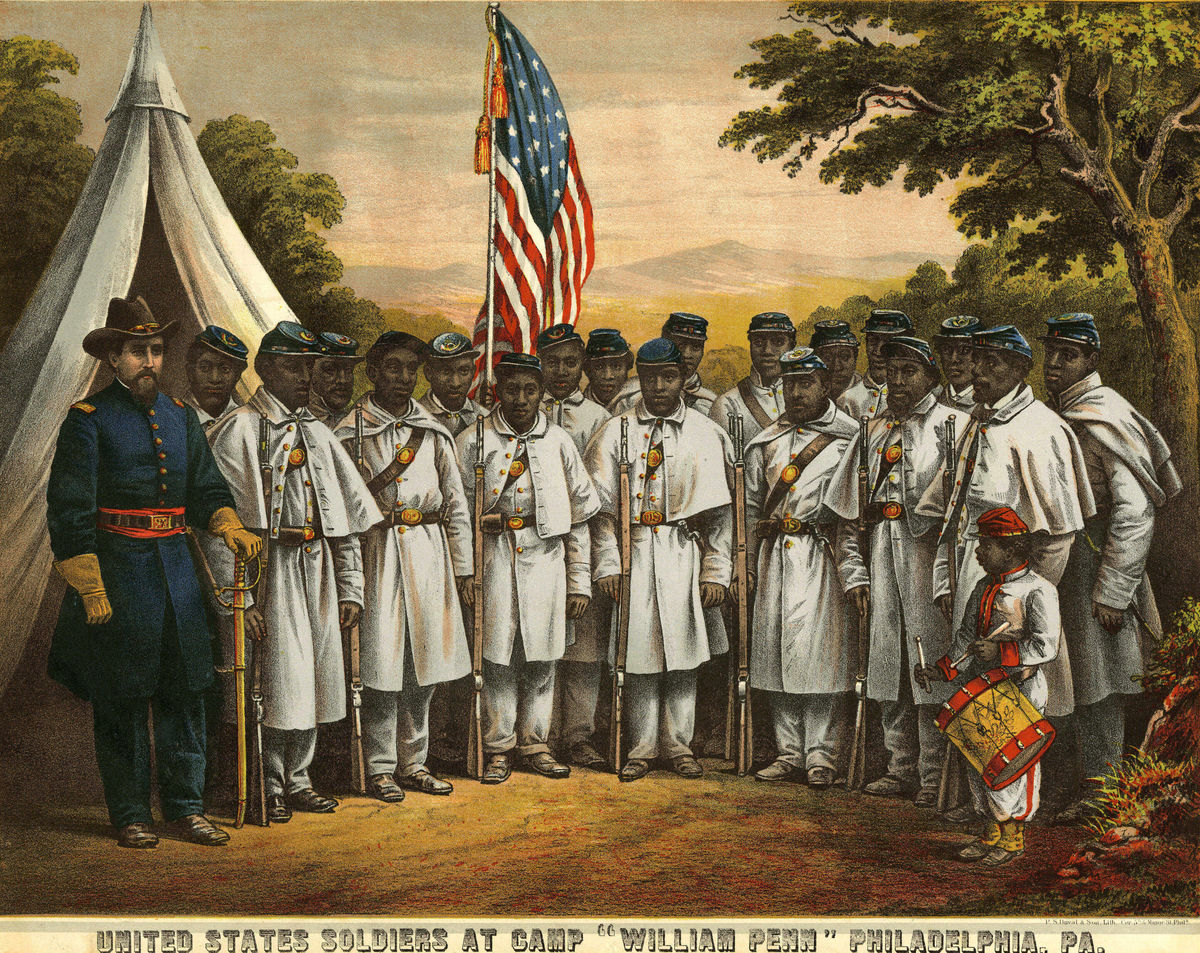

Soldiers at Camp William Penn, the first training ground dedicated to the African American troops who enlisted in the Union Army. (Illustration courtesy of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection)

Even after Granger’s order, slavery didn’t come to an immediate halt in Texas. For the 250,000 enslaved Africans in the state, freedom was denied by their slaveholders. “People of African descent: that was their main capital,” Turner said. It wasn’t in the plantation owners’ interests to free enslaved Africans. They decided when and how to announce emancipation, with some delaying until after the harvest or until a government agent arrived and forced them to make the news public.

Black people who dared leave plantations faced being killed after they escaped. And enormous obstacles remained, even after emancipation. “What is freedom in a capitalist society, without reparations? Without property?” Turner said.

Nevertheless, former enslaved Africans in Galveston chose June 19 as a day to celebrate their freedom and did so from 1865 onward, a tradition that soon spread across the country. Texas declared Juneteenth an official holiday in 1980 and Gov. Tom Wolf designated it a state holiday in Pennsylvania in 2019.

“It’s a way, especially now, to create a dialogue around this whole legacy of slavery and its impact on today’s society,” Turner said. “We’re still dealing with that, with Black bodies being violated and people being murdered and disrespected. It’s directly linked to slavery.”

The Blockson Collection annually celebrates Juneteenth with special events and programming. “Every year, we celebrate some aspect of African American history and culture,” Turner said. “What do you do in a society where the dominant popular culture is Eurocentric? We can offer an Afrocentric perspective.”

- Edirin Oputu