Exploring the best way to bring up Black children in white families and communities

“Do Right By Me,” a new book by Valerie Harrison and Kathryn Peach D’Angelo, looks at transracial adoption and the importance of fostering positive racial identity in Black children.

Valerie Harrison and Kathryn Peach D’Angelo have been having meaningful conversations about race, culture and identity for more than 20 years.

They met at Temple—where Harrison is the president’s senior advisor for equity, diversity and inclusion and D’Angelo is assistant vice president for administration and planning—and quickly became close friends, learning from and about each other.

But when D’Angelo and her husband Mike adopted their son Gabriel, her conversations with Harrison took on a new significance: now D’Angelo was learning, with help from her friend, the best way to bring up a Black child in a white family.

Together they’ve written Do Right by Me: Learning to Raise Black Children in White Spaces, a book (published by Temple University Press) that explores transracial adoption, the challenges Black children face growing up and the impact of racism on everything from education to healthcare.

We spoke with them about the book and the importance of nurturing a child’s positive racial identity.

Temple Now: What inspired you to write Do Right by Me?

Kathryn Peach D’Angelo: My son Gabriel, who is now 9 years old. My husband Mike and I are both white and we adopted our beautiful biracial son from birth. As white parents of a Black child, we want so badly to be good parents. But we have real questions and concerns about racism, culture and identity. And unlike parents, and I would say white people in general, who may subscribe to a color blind or post-racial ideology, Mike and I were very clear that we needed to confront head on the reality that we would need to equip our son for an experience that was far more complex than anything he or I had experienced in our lifetime. Luckily I have a 20-year-long friendship with Val. And as we began to have conversations about what it would take to parent a child of another race, it became more than her just sharing her wisdom with me: It was her sowing that wisdom and support and love into our future family.

Valerie Harrison: I would hear these same concerns expressed by other white women who had adopted Black children. The women who came up to me had mainly adopted daughters and they would share with me their concerns and questions about everything, from how to care for their daughter’s hair and affirm their body image to how to build a diverse community where Black female achievement was the norm. They were very concerned about that. There were TV images of Michelle Obama and Oprah Winfrey, for example. But they wanted examples of Black female leadership and achievement that their daughters could know personally and identify with as part of their community of support. So it was clear to Katie and me, from her experience as well as from these women, that white parents of Black children want badly to parent well, but they have real questions and concerns about their ability to navigate issues of racism of culture and identity. When we started the project we initially thought that the book’s target audience would be parents of Black and biracial children. But it quickly became apparent that the book is for anyone who is part of a Black child’s community, whether as a parent or grandparent, or as a teacher, coach or mentor. Really anyone who cares about their development. We also realized that the research and scholarship that we were bringing together applies not only to Black children and white families, but to Black children who have to navigate any white space, whether it be their school or their neighborhood.

TN: The book’s title was inspired by a quote from The Color Purple. Why did you choose it? And how did you decide on the photo for the cover?

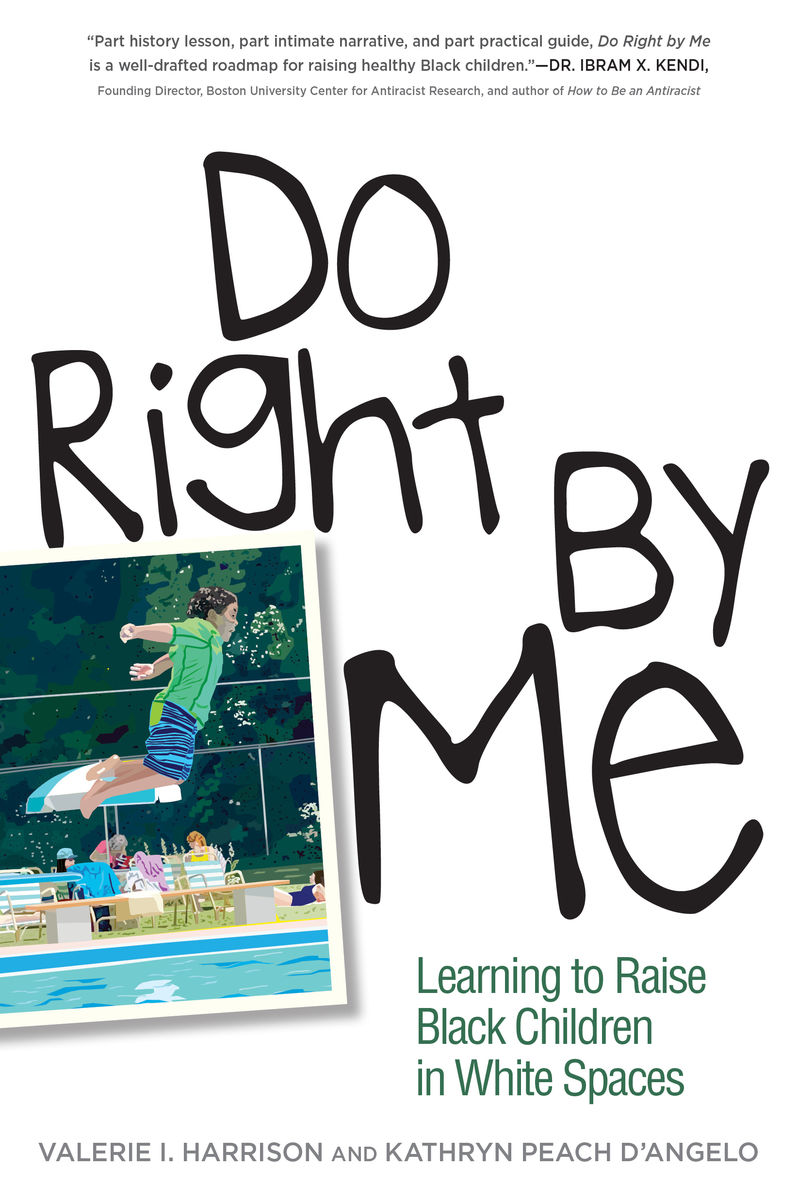

KD’A: The photo is actually my son Gabriel, the day he passed the swim test at our community pool. You have to pass the swim test before you can go off the diving board. That day he said, “Mom, I’m going to do it.” And I said, “Well, do you want to practice first? You have to be able to swim the length of the pool and back, and then tread water.” His response was immediate: “You don’t think I can do it.” And that just took the air out of me, the thought that my son might ever feel that I don’t believe he’s capable of something. I said, “If you want to go for it, go for it. And I’m going to be there cheering you all the way.” Sure enough he passes the test on the first try. And that’s his first leap off of the diving board, on the cover. As a mother, you’re constantly in this space where you want to hold your child close and protect them from everything. But you also want to prepare them to launch and leap and move forward, knowing that they have your love and support.

VH: Many people probably remember that scene in the movie The Color Purple where Whoopi Goldberg makes this proclamation, a command really, for her husband to “do right by me.” Katie made the point that at the pool Gabe, who’s a very independent-minded and confident kid, was saying, “Don’t have low expectations for me.” In the book, there’s a chapter on education that examines the research that tells us white teachers often have lower expectations for Black children than Black teachers do. So the title says, “Don’t do that to a Black child.” And there’s another chapter that deals with healthcare and it says, “Healthcare professionals, the research tells us that you have biases that make you treat him [Gabe] differently than you do a white baby who comes into an emergency room. Don’t do that to him.” The book’s title is a challenge for us to do things differently, to understand the root cause and the force of our biases and our prejudices, which we all carry. And then to make wiser decisions around them.

TN: The book’s structure is a little unusual in that it alternates between both of your voices. Why did you choose that format?

KD’A: We knew in the beginning that we wanted each chapter to have a personal story that people could relate to and identify with. But we also wanted to include a lot of research as well. Val and I are proud Temple alumni and we’re aware of the privilege and opportunity that we have of working at the university as well. We are constantly exposed to the most brilliant expertise available and we wanted to make it accessible to a broader audience. So we decided to combine personal stories, research and a practical, how-to element, i.e., now that I have this information, what do I do with it? That was structurally how we approached each chapter.

We also really wanted the book to model to others that having uncomfortable and difficult conversations specifically about race and racism is essential. The only way that we are going to move through this moment in our history and not repeat the past is if we engage in the difficult, maybe uncomfortable, conversations. And the best place to do that for Val and I was in this really wonderful relationship.

VH: Katie and I have worked together at Temple for more than 20 years and we developed a friendship in that context. We often would get the question, “Well, how do you make a Black friend?” We don’t minimize the question because one, we believe that there is a genuine desire to develop friendships across races. But more important when Katie started digging into some of the work of transracial adoptees one of them said, and we found this to be so profound, “Your Black child should not be your first Black friend if you are a white parent.” So we’ve included a chapter on developing friendships across races.

As is the case with most friendships, Katie and I have engaged with each other about a range of topics from how to deal with relationships to our value system to race and racism. However, when Gabriel came on the scene in 2011 the stakes grew from the two of us engaging in philosophical conversations to a mother trying to equip a child to thrive in a white environment, and a community trying to support her. These conversations can be difficult, but over the years we learned how to disagree in a way that was not fatal to the relationship. Because we were committed to the priority, which was our relationship and Gabe’s health and welfare. We try to demonstrate that through the book’s back and forth.

The back and forth structure also demonstrates another central principle. A European or white worldview—its history, culture perspective, body type, hair texture—is just one among many. It’s not universal. It’s not the standard. It’s just different. And it’s not entitled to supersede other perspectives that other groups proudly center themselves in. My voice is very different from Katie’s. Our perspectives are different. We tried to model that principle by giving each of us a separate voice.

TN: The book includes a discussion of Temple professor Molefi Asante’s theory of Afrocentricity and the importance of Black people being the main characters in their own stories, rather peripheral figures in a Eurocentric one. How does this theory help someone raising a Black child?

VH: The research tells us that Black children thrive when they’re raised to have a positive racial identity. Dr. Asante has spent his life and career helping Black people to do just that—to understand that history did not begin for Black Americans in 1619 on the shores of Virginia, but on the continent of Africa as kings and queens who developed the first great civilizations; to understand that they are not operating on the fringe of another group’s story, but have a story in the same way that other racial and ethnic groups do and one that they can be proud of. This makes all the difference in how Black children see themselves and it builds and doesn’t destroy their cultural esteem.

TN: You identify three forces which threaten positive identity for Black children: negative images of Black people, systems that reinforce inequality and white parents who might dismiss the need to think about race. What impact do all of these factors have?

VH: A significant threat to a child’s racial identity is negative and distorted imagery. The way that slavery, racism, terror and legally mandated discrimination was and continues to be justified and fueled is by portraying Black people as inferior, dangerous or sometimes almost as nonhuman and then conveying those images in as many outlets as possible. If you misrepresent a group’s members as savage and dangerous, it’s easier to justify savagery and violence against them. And it’s more difficult to connect and empathize with the group or see their contributions and value. Many news reports still overrepresent Black people in stories about poverty and crime and underrepresent them in stories about leadership, community involvement or family life. There was an interesting study that we have included in the book that demonstrated over a three-month period, 86% of TV news stories were about Black men committing a crime. Less than 3% of stories showed young Black men ages 15 to 30 involved in activities outside of crime. These images create perceptions of Blackness and Black people that influence a person’s behavior toward us.

We also talk about the violence of racism. For example, experiments confirm that white people are more likely to shoot an unarmed Black male than an unarmed white male. On Aug. 24, 2020, a man armed with a shotgun fired at Upper Gwynedd Township [a suburb near Philadelphia] police. Police had been called to the scene because the man was roaming in residents’ backyards. The police successfully de-escalated the matter and the news media reported that the man was taken by police to the local hospital, where he underwent detox for methamphetamine. Two months later, on Oct. 26, Walter Wallace Jr. was fatally shot by police when he walked toward them holding a knife. The police in both cases were white. The man with the shotgun was white and Mr. Wallace was Black. So it raises the question: why can’t we figure out a way to de-escalate more situations involving Black people?

KD’A: I went in for a parent-teacher conference at Gabe’s school. An assistant teacher who was new to the classroom, and who Gabe was clearly having difficulty with, spoke and one of the first things she said to me (I could tell she was nervous) was, “Well, with a name like D’Angelo I just thought Gabe was Italian. I had no idea that he was Black. And I don’t see color.” It forced me to sit back in my seat, regroup and then say, “If you do not see color, you do not see my son. Period.”

White people don’t spend some time saying, “I need to find out. I need to unpack some of this and uncover what I need to learn or understand.” If white people, white parents in particular, but also Gabe’s white teachers, doctors, ministers, coaches, if they don’t see his color, they do not see him.

Our family is middle class. We live in a nice house in a beautiful and diverse neighborhood and community. Gabe goes to one of the most well-resourced and diverse schools. But that is not enough to teach my child positive racial identity. If everyone that is influencing my child’s experience in the classroom or elsewhere doesn’t see his color, then they don’t see my child. All of the research that we acknowledge in this book points to the same thing: If you want positive outcomes for your child in any direction, then you must ensure that you are cultivating and developing their positive racial identity. And the only way that we can do that is if adults, whether or not we are the parent, commit to do that and learn and do better.

Join Harrison and D’Angelo for a virtual conversation about “Do Right By Me” at the Free Library of Philadelphia on February 4.

—Edirin Oputu