The Evergrande debt crisis, explained

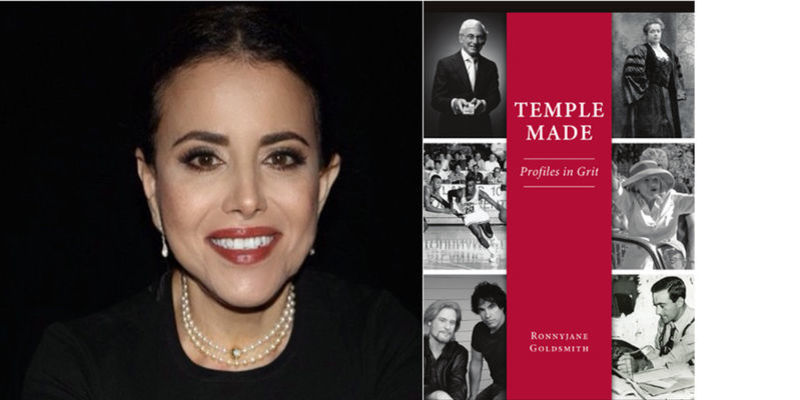

Roselyn Hsueh, associate professor of political science at the College of Liberal Arts, talks about the debt-stricken company, whose financial problems could affect the Chinese economy and global financial markets.

Evergrande is one of the largest companies in China, a sprawling corporation with interests in everything from real estate to electric cars and investors all over the world. The conglomerate’s size and reach make it the very definition of “too big to fail.”

Yet Evergrande is more than $300 billion in debt and—despite making at least one payment to its creditors—is at risk of collapse, an event which could prove disastrous for the Chinese economy and send ripples through global financial markets.

We spoke with Roselyn Hsueh—an associate professor of political science and the author of the forthcoming book Micro-institutional Foundations of Capitalism: Sectoral Pathways to Globalization in China, India and Russia—about how Evergrande became the most debt-ridden real estate developer in the world.

Temple Now: What is Evergrande and what does it do?

Roselyn Hsueh: Evergrande is a real estate developer with many different subsidiaries and it was founded by a Southern Chinese entrepreneur in the province of Guangzhou in 1996. Over the years, it’s grown to be this huge holding group that is internationally listed in Hong Kong and registered in the Cayman Islands. Within the group are several different subsidiaries and types of businesses, including renewable energy businesses. Evergrande is probably among the top three largest real estate developers and largest Chinese companies in China. And with the default, some of which has already been happening, it is going to be the largest real estate company to default on international loans in history.

TN: How did this happen? How did the company find itself in a financial crisis?

RH: The fate of Evergrande is very much rooted in the way the Chinese government has liberalized the economy since the 1978 “open door policy” and China’s subsequent accession into the World Trade Organization in 2001. It’s important to think about how Evergrande could have been founded in what many people imagine is a state-controlled economy. When the Chinese government began to liberalize the country’s economy, it held on to strategic assets and industries on the one hand, but also decentralized very widely [on the other], ceding control over the parts of the economy that it did not consider to be extremely strategic—to the national technology base, security applications and so forth—to local government and business stakeholders. This means that a huge part of the Chinese economy is decentralized to the local level, to the provinces, municipalities, towns and villages.

The owner of Evergrande, Xu Jiayin, came of age in this environment of what I call a bifurcated capitalism: On one hand, you have the state-controlled economy and on the other you have the introduction of private and also local state competition.

But one of the unintended consequences of decentralizing and deregulating is that it then did not necessarily create a structure that could keep certain parts of the economy well-regulated. So, you have a situation where there are a lot of new stakeholders, a lot of government and private entrepreneurs (many of whom might have been state employees or Chinese Community Party members) who are basically operating in a part of the economy that is essentially the wild, Wild West.

And now we have Evergrande, this huge real estate company with international stakeholders all over the world, and institutional ones as well as individuals, that is poised to perhaps lose a lot of money. For some institutional stakeholders and private investors, this could mean their entire financial well-being. It’s because we have this part of the economy that has been left at the whim of a lot of competing interests within China and hasn’t necessarily been well-regulated.

TN: Why are people in China worried about the possibility of Evergrande going into default?

RH: Individuals, local decentralized stakeholders and the central government are very nervous. Evergrande has only expanded its economic power over time. Its reach is beyond just the province of Guangzhou, in southern China. It actually reaches most of China’s different provinces and many of its cities and localities. And when so many of China’s 1.4 billion people are affected, the Chinese government and its leadership are nervous because political stability is at stake. The legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party is at stake. So, what had been a local, decentralized problem is now a national problem.

There are already reports saying the Chinese government is beginning to do something about it. Some of Evergrande’s assets and liabilities have been taken over by state-owned banks. Evergrande, which so far has been largely a private company, is now going to receive financial intervention from the state. The Chinese federal government will have central control, which could be a problem for Evergrande’s multiplicity of stakeholders, including the global ones.

TN: What effect is the Evergrande situation having on international financial markets?

RH: In 2009, I believe, was when Evergrande became internationally listed at the Hong Kong stock exchange. An international listing means there should be transparency of business dealings. But one of the biggest complaints is that there’s been a lot of murkiness about what’s happening within Evergrande in the last several years, and even now with the central government’s intervention. That is a problem for international stakeholders, because they don’t know what’s going on. And it appears that the stakeholders that are going to be prioritized in any bail out by the Chinese government will be the Chinese stakeholders, not the global ones. That’s why the global stakeholders are nervous. Up and down different levels of business and different levels of financial authority, people are nervous globally.

TN: What’s next for the company?

RH: A big part of it will be dependent on central-local relations in China. Because of the decentralization of markets, the Chinese central government will have to contend with the multiplicity of stakeholders, including local government ones. There are local authorities that need to be taken into account. What happens next will have implications for the future of bifurcated capitalism within China. And we potentially may see more central intervention and control. At the same time, the Chinese government might decide that it still wants local governments to have a stake. In that case, we might see Evergrande making a series of bargains with local governments, some of which will most likely prioritize the domestic stakeholders. This doesn't mean that global stakeholders are going to be left out of the equation entirely, it’s just that they may not be prioritized in the immediate future.

—Edirin Oputu