CLA professor at center of translation renaissance

|

|

|

|

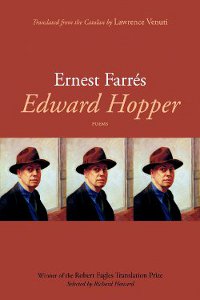

At a time when “thinking globally” has become a mantra, Temple English professor Lawrence Venuti is leading the charge — in literary circles, that is. Venuti, an internationally renowned translator and translation theorist, wants both translators and readers of translations to be more mindful and appreciative of the cultural differences they encounter in a foreign text. His latest project, a translation of Ernest Farrés’s Edward Hopper (Graywolf Press, November 2009), won the second annual Robert Fagles Translation Prize, sponsored by the National Poetry Series. A leading theorist in his field, Venuti is at the forefront of what might be called a translation renaissance. Once invisible in their behind-the-scenes roles, translators are increasingly recognized in academic and publishing arenas for their contributions to the literary process. |

|

|

The most prevalent translation strategy has been to adhere to the current standard dialect of the translating language, which is the most familiar and least noticeable to the reader. This kind of translation, according to Venuti, effaces the translator’s presence and erases cultural distinctions.

“Translation rewrites a foreign text in terms that are intelligible and interesting to readers in the receiving culture. Doing so is akin to committing an act of ethnocentric violence by uprooting the text from the language and culture that gave it life. Translating into current, standard English at once conceals that violence and homogenizes foreign cultures,” he said. According to Venuti, no translation can provide its reader with an experience that equals that of its native reader. He believes that the translator must call attention to the strategies used for bringing the foreign text into a different culture. Highlighting this process signals respect for the literary traditions, linguistic turns and the social moment that produced the original text, he said. Farrés’s Edward Hopper, a collection of poems based on the paintings of the 20th century American realist painter, presented Venuti with the perfect opportunity to do just that. “Browsing in a bookstore in Barcelona, I came across an intriguing project — who was this unknown poet tackling an American icon? Why Edward Hopper? Why in Catalan, a minor language?” said Venuti. “Here the focus would be not just on the text, but the artwork; not only on the literary traditions of the receiving culture, but on the critical reception of the artist. The Catalan poetry held the promise of defamiliarizing a mythic American painter,” said Venuti. Farrés organized his poems to sketch a biographical narrative that was Hopper’s, but also his own. Both had small town origins; both went on to big cities. In the poems, even Spain and the U.S. are conflated. For example, the poet might describe a picture of Cape Cod, but he mentions fig trees and lizards. Such obvious discrepancies were intentional,, said Venuti. Venuti immersed himself in everything Hopper. He found that the painter spoke in a very rich vernacular, so wherever he could maintain a semantic correspondence, he included some of Hopper’s own language. |

Listen to Lawrence Venuti's Translation  Compartment C, Car 293, 1938

From Edward Hopper: Poems by Ernest Farrées Translated from the Catalan by Lawrence Venuti Face stern, hair The down time on the train was just Venuti’s translations purposely use non-standard English colloquialisms, slang and dialect, requiring the reader to read the translation as a translation. In the above poem, swell—not Standard English, not even contemporary slang—was commonly spoken by American painter Edward Hopper, so Venuti selected it when bringing this poem, which describes Hopper’s 1938 painting, from Catalan into English.

|

|

“In the translation, there is a layer of American vernacular from Hopper’s period that is not in the Catalan text,” he said. “It’s a way to bring Farrés’s poems closer to Hopper but also to enhance the differences.” Venuti’s road to success as a translator began unexpectedly in South Philadelphia, where as a youth he absorbed the Italian dialect spoken in his grandparents’ home. “You would learn mostly civilities, but also the words they called you when they pulled you by the hair,” he said. Later, as a doctoral candidate at Columbia, he decided that as an Italian American, he should learn Italian — the language he is now best known for translating — and he immediately began to translate. “I found tremendous gratification in being able to turn the foreign language into English. Solving the linguistic issues was like doing math problems,” he said. Today, Venuti’s impressive collection of translations includes everything from Gothic tales to scandalous contemporary best-sellers. The stylistic innovations he undertakes in his translations are called “elegant” and “brilliant” by reviewers. “When I devise a translation project, my aim is to write a translation that will make a linguistic and cultural difference in English,” he said. |

|