Family reunions create lasting bonds

To those on the outside, the gathering at the home of Clarence Still in Lawnside, N.J. might look like just another weekend celebration. But for the hundreds who attend the Still Family Reunion it means much more.

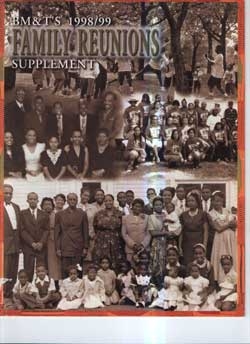

Each year, close to 400 extended family members reunite to celebrate the legacy of one of the nation’s most prominent African-American families. William, one of the Still family’s most notable patriarchs, was an abolitionist, a conductor on the Underground Railroad and one of Philadelphia’s first successful businessmen.

The event is a high-profile example of the importance of family reunions in African-American culture, a phenomenon Temple Professor Emeritus Ione Vargus has been studying for more than 25 years.

“Black families participate in reunions in what I believe are numbers and percentages and with a consistency to which no other group can make claim,” said Vargus. “For a long while it had the characteristic of a movement, as each year, more and more families held their first reunion.”

The Still reunion is large compared to other gatherings that happen every summer across the country. In some instances, planning of reunions takes on a formal organizational structure, with fundraising, committees and in some cases, articles of incorporation. But, no matter the size or complexity, each reunion is of equal importance to the individuals who attend.

“Some say the African-American family is dying. I say it lives on,” said Vargus, founder of the Family Reunion Institute at Temple. “Family reunions have become a part of the permanent fabric of this country’s society. This has particular significance because individuals and families control the reunion as an institution. There is no dependence on government and little dependence on monies outside the family. The participants are willing; the goals are meaningful.”

In the summer of 1986, Vargus began following the movement north to Boston and south to the Carolinas and at all stops in between. She spent months collecting data at 14 reunions, where she conducted in-depth interviews as a participant-observer.

“Initially, people were surprised that I would be interested in what they were doing because they were ‘just having a family reunion,’” said Vargus. “However, I felt that there must be something very important about a reunion.”

Through questions, interviews and observations, she realized that there were many benefits to the reunion that families didn’t recognize. The reunion is much more than just a family gathering, she said. Through the reunion, families carry on a custom that is rooted in African-American tradition.

“For black people, slavery in this country disrupted the family, the most essential structure, since slavery allowed for no legal marriage, no legal family and no legal control over the children,” Vargus explained. “As soon as slavery ended, women and men went about trying to put the family back together. The stories of former slaves trying to locate their families is inspiring, to say the least. And many of these stories are told at the reunion.”

Vargus’s research led to the creation of the African-American Family Reunion Conference in 1988, which attracted families from all over the country who were interested in planning and maintaining their own events. She went on to establish Temple’s Family Reunion Institute in 1990, the only organization of its kind in the United States. Since retiring, she has served as a volunteer for the organization.

In addition to working with African-American families, Vargus helps families of other nationalities plan and execute reunions across the country.

“Dr. Vargus is an example of how researchers directly benefit the everyday lives of the community-at-large,” said Diane Turner, curator of the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple. “She receives numerous calls throughout the year from individuals seeking her advice and expertise; she’s one of Temple’s treasured historians.”

Vargus served for 17 years as dean and associate dean of the School of Social Administration. She was both the first African-American and the first female academic dean at Temple.