In her new book, Temple professor Laura Levitt contemplates ordinary losses in relation to larger Jewish histories.

In her new book, Temple professor Laura Levitt contemplates ordinary losses in relation to larger Jewish histories.

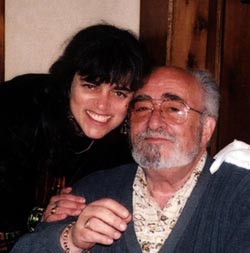

Photo by Phyllis Levitt

The author is pictured here with her father, Irving Levitt.

|

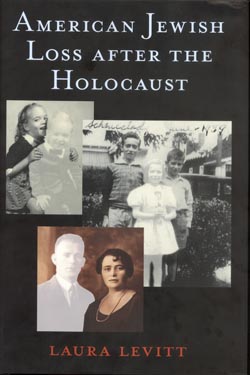

Personal stories and family photographs may not be the first things you expect to find in a scholarly academic text, but that is exactly what you get when you open Laura Levitt’s American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust, published this month by New York University Press.

“It seems to me that for a long time, many American Jews like me have failed to reflect upon or even value our ordinary family stories. A lot of us have grown up in the shadow of the Holocaust with taboos about what it means to be respectful of those losses. We have learned to remember the Holocaust by saying, ‘There is nothing else like it,’” explained Levitt. As a consequence, the associate professor of religion and director of Jewish Studies added, the urgency of the Holocaust has rendered ordinary losses inconsequential. |

|

By offering a meditation on the ways in which these different losses touch and illuminate each other, American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust posits that one way of fully commemorating the Holocaust is to reflect upon the losses of our everyday lives. In her book, Levitt explores the story of her two grandmothers, one of whom died when her father was very young and the other who raised her father and figured prominently in her own childhood. Said Levitt, “I use my family photographs and my family story, not because my story is unique, but as an illustration of how these losses can touch and be touched by more authorized legacies of Jewish loss. “The fact that my story is not unique should serve as a kind of invitation to my readers to look again at their own family stories.” |

|

|

Juxtaposing her own intimate narratives of loss with close readings of Holocaust memorials, such as the Tower of Faces in the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Levitt creates formal connections between the losses. “Thinking about these losses next to each other allows us to see our place in the broad span of Jewish history,” Levitt said. She admitted that some publishers did not at first see where her work fit in; it’s not traditional scholarship, nor is it fully a memoir. But, according to Levitt, first-person accounts are not totally foreign to academic work — they emerged from feminist identity politics in the 1980s and as a response to post-structural critiques of the Self. In addition, she said, her work very much follows in the tradition of contemporary anthropologists and ethnographers who place themselves at the center of what they study. Despite some passages of very close textual analysis that she has described as only for the most “intrepid reader,” Levitt still hopes her work is accessible to a non-academic audience. “I am interested in making academic discourse not so distancing and in saying that critical work matters.” |

|

|

Her inclination to challenge academic barriers began with Jews and Feminism: The Ambivalent Search for Home in 1997. “My first book explored how many of the narratives and traditions that shaped who I am, such as Judaism, liberalism and feminist theory, were rattled and challenged by having been attacked in my home — raped by a stranger — who tried to kill me.” Building on this previous work, Levitt’s American Jewish Loss after the Holocaust crosses boundaries and offers a new model for what engaged Jewish feminist scholarship might look like. |

|