Taking it to the Streets

Story by Renee Cree, SMC ’12

Photography by Ryan S. Brandenberg

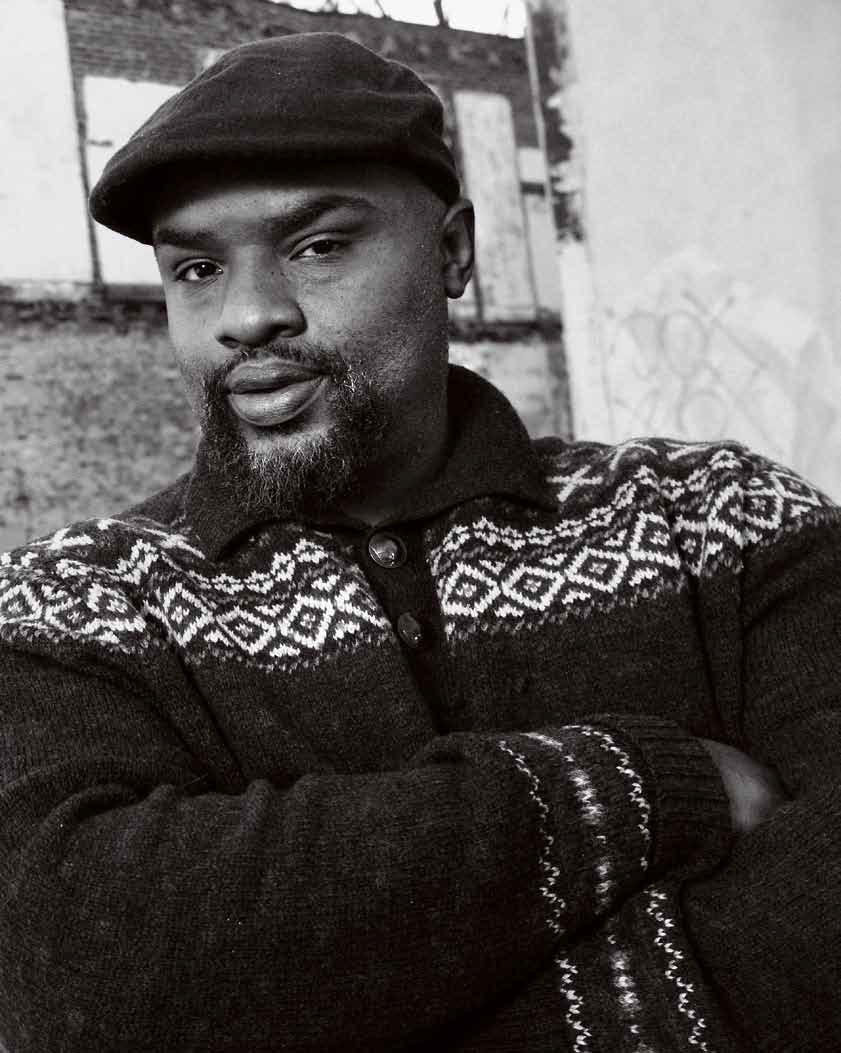

Terry Starks used to walk the streets of North Philadelphia, heavily involved in high-risk street activity such as drugs, money and aggression.

Though he might not look physically imposing or swagger like a stereotypical thug, he has seen and done it all, and it never occurred to him to escape that lifestyle. According to Starks, it was business as usual.

“I made some bad choices,” he says. And then, in 2002, Starks was shot four times in the chest while being robbed. He spent 19 days unconscious, and still carries a bullet in his heart.

After that, he says, the fragility of life became clear to him. Something had to change, and he decided to use the money he still had for something positive. He bought property in North Philadelphia and built a barber shop for the community. Wholeheartedly committed to the business, he lived above the shop while it was being built. From his profits, he opened two other businesses in that same building: a recording studio and a record store. He also began mentoring some of the young men in his neighborhood.

That drive to help his neighbors is what led him to a job with Philadelphia CeaseFire, a program based in the Center for Bioethics, Urban Health and Policy in the School of Medicine at Temple that aims to curb gun violence in North Philadelphia. It is the latest Temple effort to further reduce violence in that area. (The first was called Cradle to Grave—a controversial, yet effective, program that exposed young people to gunshot victims.)

Now, Starks is back on the streets. This time, he is an outreach worker, canvassing a beat within the 22nd Police District that extends from 22nd Street to the Schuylkill River and from Diamond Street to Lehigh Avenue. Starks talks with community members who knew him before he turned his life around, with the hope of making inroads with some of the young men in CeaseFire’s target demographic: those ages 14 to 25 who are involved in high-risk street activity, such as guns and drugs, and are interested in turning their lives around.

STREET CRED

Outreach workers such as Starks have street credibility; three of them working with Philadelphia CeaseFire are ex-offenders. They act as advocates for their clients, contacting them on a regular basis and trying to redirect them toward employment, job training and education.

In one instance, Starks says he even helped save a client on the verge of being sent to jail for parole violation.

“I sat and talked with his parole officer, and explained that he was on a new path, involved in this new program, and that I would take full responsibility for him,” he says. The young man avoided jail time and is now enrolled at Philadelphia Community College.

Starks says that life experience is a powerful tool in breaking through to the young men he mentors. “A lot of these guys know me from before I was shot, when I was doing the wrong things,” he says. “They see that I can relate to them because I know the lifestyle, but I also am coming to them as a gunshot victim.”

The fact that Starks is so well known in this community—both as a mentor and as someone who used to “live the life,” as he says—helps him make the initial contact. “I’ll see them standing on the street corner, and some of them will speak to me before I approach them,” he says. “They’ll say, ‘What's up, O.G. [original gangster]?’ It gives me the opportunity to address the entire group, to tell them where I used to be and where I am now.”

Starks explains that he is there to help them turn their lives around; that he knows what it’s like—that he was there too; and that he doesn’t want to see them in the emergency room, as he was.

“I give them an ultimatum,” Starks says. “‘We can talk now, or we can talk when you're laid out with a gunshot wound. It's up to you.’”

Starks then offers his business card and says he can help. For him, it has been an effective strategy. Most CeaseFire outreach workers aim for a full caseload of 15 clients. Though the program began in July 2011, Starks has all 15 clients already.

While this method of employing ex-offenders to prevent gun violence might seem unorthodox, the data show that it works. The original CeaseFire program, launched in Chicago in 2000, blends statistical information and the knowledge and experience of community members to focus efforts on individuals most at risk for gun violence: those who come from a low socio-economic background, live in an area with a high rate of violent crime and have a history of violence.

In 2008, the Department of Justice issued a report on CeaseFire’s effectiveness and found a reduction of up to 73 percent in the number of shootings and killings in areas of Chicago where the program was implemented. Marla Davis-Bellamy, director of Philadelphia CeaseFire, calls the rise in gun violence across large U.S. cities “a public-health epidemic.” One of the keys to CeaseFire’s success is that it treats gun violence as such, focusing on engaging communities and changing behavior.

“We work collectively with community and faith-based leaders who have the ability to influence the thinking and behavior of young people who are losing their lives to gun violence,” she says.

PUBLIC UNITY

In addition to its man-on-the-street technique to prevent violence, members of the outreach team respond directly to shootings, typically by holding a march or a vigil conducted at the site of a shooting within days of a homicide. They also saturate the targeted neighborhoods with posters, leaflets, flyers and other materials that disparage violence and carry pointed messages about the consequences of shootings and killings. Additionally, Temple University Health System refers gunshot victims to the CeaseFire program.

At a recent march, a group of community members followed the Philadelphia CeaseFire team, clad in bright orange shirts, while holding signs and flyers with the simple message to “Stop. Shooting. People.” Former outreach worker Brandon Jones, armed with a megaphone, urged community members to join the cause.

“We’re here because we think change can happen here,” he called out. A chorus of voices, all repeating the mantra “Stop! Shooting! People!” rose up behind him.

Outreach Coordinator Quinzel Tomoney, a seasoned outreach worker with a background in after school programs and summer league basketball, directly supervises the outreach workers. He has worked with at-risk youth for years, and is driven to get them off the street and change the direction of their lives.

Tomoney is an asset to Philadelphia CeaseFire because he also can relate to those who need his help. “I’ve done it, and I see it happening over and over again,” he says. “The trouble is, there is no structure at home. There’s no stability there.” Tomoney aims to guide at-risk youth toward responsible decision-making that will have a positive effect on their futures.

The organization, funded by the Pennsylvania Commission on Crime and Delinquency, is collecting data to determine its effectiveness in the 22nd district. If it is successful there, the goal is to extend the program to other areas of the city.

Davis-Bellamy is confident that the success of Chicago's program can be replicated in Philadelphia. “You have to work one-on-one with at-risk youth to help reverse this poisonous behavior in favor of positive pursuits, such as mentoring others, and it's what we've found to be very effective,” she says. “We are taking an interest in these young people, which is a new experience for some of them. It's the first time anyone has shown them that they care.”

Starks’ entrepreneurship and community involvement are powerful evidence of where those positive pursuits can lead. For his mentoring and work in the community, he was recently honored with a humanitarian award from Pennsylvania Sen. Shirley Kitchen, SSW ’75—a far cry from 10 years ago, when he was fighting for his life.

“The biggest thing we can do is to help set goals and make plans for these kids to have a positive future,” Stark says. “If we don't, they’ll just fall right back into their old habits.”