Sinking into Smart Art

Robert Blackson arrived at Temple Gallery in mid–2011. Since then, he has organized a staggering—and unorthodox—level of programming, from a mobile blood bank to 10 audio exhibits about moments of silence, to draw attention to a variety of social issues. At the time of this interview, the gallery featured a performance–art piece by Philadelphia artist Tim Belknap. Over an eight–week span, Belknap donned a NASA suit and suspended himself in a giant white cube outfitted like a spaceship. In this setup, he used the internet conferencing software Skype to talk to local fourth graders about space exploration. Blackson says the artist was inspired by the shuttering of the NASA program.

HOW DO YOU CHOOSE WHAT WILL BE EXHIBITED IN THE GALLERY?

We have an advisory council, made up of people from across campus and Philadelphia. When we meet, everyone brings a question they don’t know the answer to. A discussion ensues about the different issues posed, and we vote. Based on the votes, we decide how much space, money and time to devote to [exhibits in] the gallery.

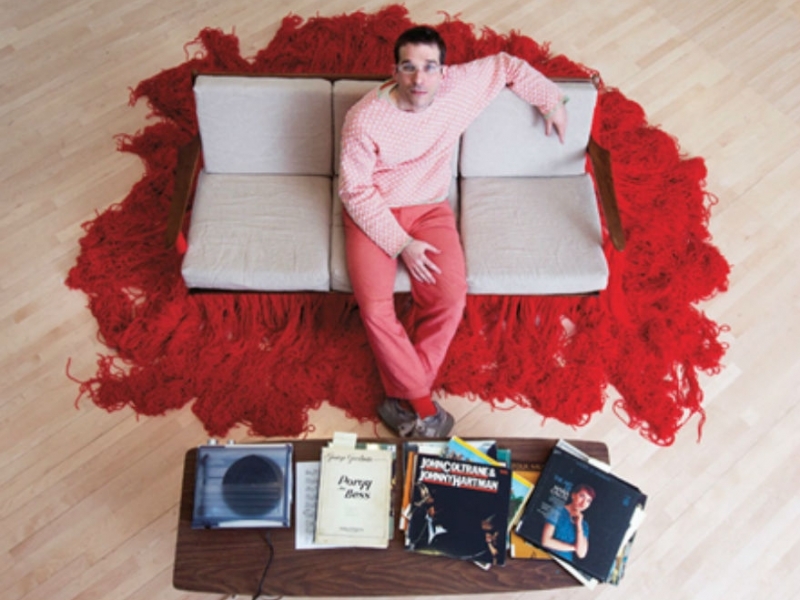

Robert Blackson sits among two artworks: “Love Songs”—the records on the table, chosen by Lucas Henry in the Boyer College of Music and Dance—and “I<3 CZ,” a fiber sculpture by Susie Brandt made from 120 skeins of yarn.

Robert Blackson, curator of the Temple Gallery at Tyler School of Art, explains the gallery’s mission, and what’s behind a somewhat unorthodox installation.

IS THAT DIFFERENT FROM HOW OTHER GALLERIES OPERATE?

It is. Usually, a curator relies on what they’ve seen in the art world, such as what kinds of exhibits they’ve seen, the types of artists they know—things like that. But here at Temple, our mission focuses on what we need to learn about now.

CAN YOU PROVIDE AN EXAMPLE?

In 2011, we had the Big Shale Teach–In to discuss the issue of fracking. It’s a topic almost all of us are interested in, whether you’re an artist, a geologist or a mother of four worried about your drinking–water supply. We involved a number of speakers from across campus and across the city, to come together to talk about what it means to drill thousands of feet below us, break apart a rock and try to extract the gas within that rock without harming the environment.

WE’VE HEARD THAT YOU MAKE YOUR OWN CLOTHES. HOW DID THAT START?

That came out of my time [in art school] in Scotland. I arrived in January, and was not prepared for how cold it was. I didn’t have enough clothing, but there was a sewing machine available to students, and I could get fabric cheaply, so I decided to sew things to keep me warm. I’ve been doing it ever since.

WITH CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS LOSING MONEY AND SCHOOLS ENDING THEIR ART PROGRAMS, HOW DO YOU MAKE THE CASE FOR ART’S IMPORTANCE?

Art instills in us a sense of humanity; we are drawn to it, believe in it and value it. Even amid the destruction and negativity [in the world], there’s a sense that art should be saved. I think that’s been borne out by history. If you visit ancient places such as Greece, they didn’t keep the notes on city–council meetings or voting registration cards; they preserved really curious objects instead.