Caught in Chaos

Story by Jared Malan, POD ’13

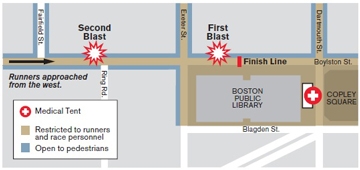

For the past 28 years, students in the School of Podiatric Medicine at Temple have treated runners at the finish lines of some of the country’s most grueling races, giving the budding medical professionals opportunities to see patients in real‐world settings. But after two bombs detonated near the 2013 Boston Marathon finish line, students who were prepared to examine feet and ankles were thrown into treating trauma. Here, Jared Malan, POD ’13, recounts what happened that day.

In my hometown of Shelley, Idaho, homegrown national heroes are scarce. One person I looked up to was Raymond Curtis Brinkman. As a boy, Curt lost both of his legs and suffered horrible burns in a farming accident, yet he was determined to continue being active. He found personal peace and accomplishment racing in his wheelchair. In 1980, Curt became the first para‐athlete to win the Boston Marathon. He went on to compete in the Paralympics, winning eight medals, five of which were gold.

Curt is a hero to people in Shelley: Curt Brinkman Park honors him; children are read excerpts of his books, The Will to Win and Still Winning/Lessons for Life. I remember hearing about Curt in first or second grade, and he made me want to attend the Boston Marathon to cheer on the runners—especially the para‐athletes.

I got my first chance to attend the race this year. I had been a member of the Sports Medicine Club at Temple for four years, and my personal crowning achievement as a podiatry student was finally here! But due to a scheduling error, I was bumped from the list of volunteers. For nearly a month, I begged Jonathan Kaplan, director of podiatric medicine for the marathon, to let me participate. I offered to drive my classmates to Boston; I offered to go as an observer. Thankfully, Howard Palamarchuk, CLA ’75, POD ’79, director of the sports medicine program in the School of Podiatric Medicine, found me a spot on the trip.

When I got word that I’d be going, I was ecstatic. My wife Chelsea has heard me talk about this trip for the past four years, and she was happy I was able to go. She is a pharmacy student at Thomas Jefferson University, and she had a test the day of the marathon. I think she was happy she would be able to study over the weekend without me pestering her. Before walking out the door, I wished her luck on her test and kissed her goodbye.

We arrived in Boston that evening, Saturday, April 13, and attended a Red Sox game at Fenway Park on Sunday—another dream of mine. After the game—it was a great one; Boston won 5‐0!—we returned to our hotel. I was elated that by the next day, I would finally be at the Boston Marathon and have a seat in the med‐tent at the finish line.

5:30 A.M.

I awoke the next morning, and sat in bed thinking about sports medicine and the foot and ankle injuries we might encounter at the race. I thought about Curt and what he did in Boston, and woke up the rest of my classmates to be sure we’d be there on time. As we arrived in downtown Boston, we could feel the excitement. The whole city was prepared for the race. Police were everywhere. Buses were shipping runners to the race’s starting point on East Main Street. As I walked the city streets, I couldn’t stop smiling.

During the debriefing for the race’s medical volunteers, we listened as the medical director of the marathon, Pierre d´Hemecourt, spoke to us about medical protocol. Race Director Dave McGillivray, Boston Emergency Medical Services Chief James Hooley and a local cardiologist also spoke to us, and then we broke out into our individual specialties. I was the last podiatry volunteer to receive a medical jacket. It was an XL, and even though I was swimming in it, I loved it. I was ready to see the runners. We rushed to the med‐tent.

9:00 A.M.

When the race started, it was a brisk 53 degrees, an absolutely beautiful day, perfect for racing. I was assigned to Bay 19 near the entrance of the tent and only 25 yards from the finish line. The para‐athletes finished first. As I saw the seated athletes roll by, I thought of Curt and was proud of Shelley, Idaho. As the morning wore on, we treated runners for common injuries like bruises, sprains and blisters. I was in the zone; I’d explain to patients where their issues might stem from, treat them and send them on their way.

2:45 P.M.

I was treating a soldier who had jogged carrying his 80‐pound military rucksack. His feet were bruised and blistered, and he was suffering from heat exhaustion, chills, and a lack of fluids and electrolytes. I bandaged his feet for the next 15 minutes, until—BOOM! The earth shook, followed by another blast a few seconds later. I looked at the soldier, and he looked at me. “That’s no good,” he said. Doctors asked each other if a generator had blown up.

All I could think about was Chelsea and my family. I knew it was an explosion. I prayed and was ready to run. I exited the med‐tent to call my wife and left her a message.

“I love you. If this is it, know I love you. I am okay, just scared.”

The sirens began to wail and screams filled the air. “If this is it,” I thought, “if I am going to die right now, I might as well die doing what I came here for.”

I walked back into the tent and saw the first casualty of the explosion: a man, limp, in a wheelchair. Half his face and the entire right side of his body had caved in from the force of the explosion. The skin and muscles on his right leg had been torn off, and his tibia and fibula were exposed. He was bleeding profusely, leaving a trail from his wounds. I ran back to Bay 19 as the horror continued. After setting up beds for the wounded, I put on gloves and waited. I stood next to my classmate Marti Randall, Class of 2014, and we watched as the EMTs sprinted out to bring back the badly injured. We were both pale and speechless. Everything smelled like gunpowder, blood and burnt flesh.

3:00 P.M.

The first patient I treated personally came in about five minutes later. She was a woman in her 60s, bleeding through her pants on her right upper thigh. She was crying and worried about her granddaughter, from whom she’d been separated.

In fall 2011, I had taken a course in traumatology, during which I spent a month working at Temple University Hospital. I had rotated through the hospital twice more in 2012, so I had seen some trauma in my short medical career. But I wasn’t prepared for this. I had learned to do primary trauma surveys—the ABCs of traumatology—from my professor, Jason Piraino, POD ’03, ’07: check airway and cervical spine, breathing, circulation, disability and exposure. Those are all key in evaluating and treating a patient with a traumatic injury, and ensuring the best chance of survival. Piraino’s instructions ran through my mind that afternoon in Boston.

I looked at the bleeding woman and said, “Hello, my name is Jared. I’m from Idaho. What is your name?” “Mary,” she responded.* After confirming that she didn’t have a spinal injury, I was so full of adrenaline, I picked her up and put her on the examination table without anyone’s help. Marti and I checked her vitals quickly. There was blood everywhere. She was bleeding out through her thigh.

I tried to take off her pants to get to her wound. “Cut them off!” Marti yelled at me. She and another classmate, Matt Rementer, Class of 2014, helped me cut off Mary’s pants and locate the wound. She had a piece of shrapnel lodged in her leg. For the next 20 minutes, we applied pressure to the site and attended to other wounds on her body. Eventually, she was taken away by an ambulance.

Throughout the ordeal, the public announcer in the med‐tent was like the voice of God, directing the triage process. We organized the injured by the severity of their conditions, and in Bay 19, we saw numerous leg injuries. For the next hour, medics attended to patient after patient, and we podiatry students helped in any way we could. Primary trauma surveys were carried out on those to whom we attended.

4:00 P.M.

Within an hour, the worst of the injured had been taken away by ambulance, and we had to evacuate. We didn’t know if public transportation was safe or even working, so we walked the five miles back to Cambridge. Jenny Lipman, POD ’13, and Lara Stone, POD ’13, were familiar with Boston and led us out. Larissa Hatala, POD ’13, kept us calm. Aaron Haire, POD ’13, who has always been a peaceful force in our class, was like our guardian, following closely behind us. Since I had no cell‐phone service, Alicia Canzanese, POD ’13, let me use her phone.

As we walked, we heard reports of police finding other explosives. We heard that a library had been bombed. (Later, those reports were confirmed to have been false.) We all tried to send text messages to family and friends: “I love you; I am okay.”

We weren’t sure if we would be able to leave the city if we stayed there any longer, so we jumped in my car and raced back to Philadelphia. On our way home, we saw a wave of FBI vehicles speeding toward Boston. Allyssa Jones, Class of 2014, and Haywan Chiu, POD ’13, kept saying they could smell gunpowder. We made it back to Philadelphia late Monday night.

After kissing my wife on the forehead, I collapsed onto my bed. I woke up the next morning shaking, still thinking about a child I saw carted off by the EMTs. I cried in the shower, and I still could smell the scene we left in Boston.

I still have flashbacks. And I still wonder why it happened at all. But some questions don’t have good answers. The only good that can come from something like that is to gain perspective. I feel that I’m more thankful for what I have. I pray more fervently and try to complain less. I care for others more deeply, and let my family know more often that I love them. I hold Chelsea a little tighter. I pray for peace, and live to bring about that end.

Jared Malan, POD ’13, graduated with a doctor of podiatric medicine degree in May. This summer, he began a three‐year medical residency at the Temple‐affiliated St. Luke’s University Healthcare Network in Lehigh Valley, Pa. He hopes to specialize in sports medicine.

*Mary’s name has been changed.