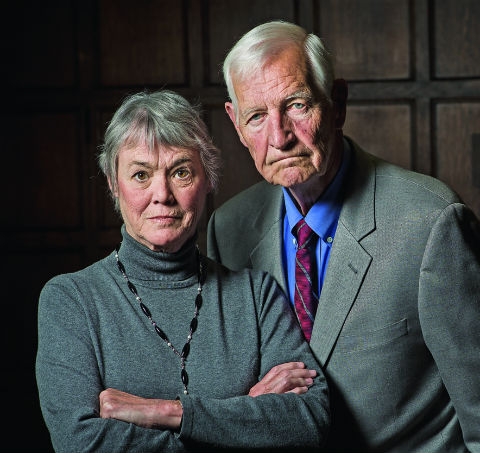

The Truth Tellers

On March 8, 1971, John Raines, then a professor of religion at Temple, and his wife, Bonnie, EDU ’72, ’79, participated in the robbery of an FBI office in Media, Pennsylvania, that exposed evidence of a massive domestic- spying program against Vietnam War protesters undertaken by bureau Director J. Edgar Hoover. The event was documented in the 2014 book The Burglary by Betty Medsger. The Raineses and the six people with whom they worked were never charged with committing the crime, but its effects were far-reaching and contributed to reforms of the FBI’s intelligence-gathering practices. Their findings also led the Department of Justice to create investigative guidelines for the bureau.

More than 40 years later, another Owl brought to light the activities of officials in Washington, D.C., operating outside the public eye. As an intern with McClatchy DC, Ali Watkins, SMC ’14, helped break a national story that detailed an apparent feud between the CIA and the Senate Intelligence Committee over a congressional report on the CIA’s detention and interrogation pro- gram. That article, the first of several, cites sources who say the CIA monitored computers Senate aides used t prepare the report.

Here, Temple talks with the Raineses and Watkins about their roles as agents of change.*

LET’S START WITH THE EVENTS OF MARCH 8, 1971. DID YOU HAVE ANY IDEA WHAT YOU’D FIND OR WHAT THE FALLOUT WOULD BE?

John Raines (JR): No. Most of us had been involved in the civil rights movement down south, and we knew that Hoover was dead set against that movement. He was using all the dirty tricks he could to try to stop it: massive surveillance, infiltrators, informers, blackmail. Indeed, he tried to blackmail Martin Luther King Jr. and suggested the only way of saving his reputation was to commit suicide—that came directly from Hoover’s office. When we got involved in the antiwar movement, we were pretty sure Hoover would try to use all his dirty tricks again, but we had no way of proving it. We had to get evidence—and what better evidence than [the FBI’s] own files, in their own handwriting?

Bonnie Raines (BR): There was a possibility that we had put ourselves in jeopardy and not found any of the evidence we were hoping to find. But it didn’t take long before we found some pretty shocking information: a note sent from Washington to agents, in particular those in Philadelphia, telling them to increase paranoia; give the idea that there was an FBI agent behind every mailbox. We knew that surveillance and intimidation had been going on, but there it was, in a document. That was a pretty exhilarating moment.

HOW WAS THE GROUP ABLE TO GET INTO THE OFFICE?

BR: One of my roles was to case the building in Media, to sit in the car at night and watch the activities in the area and get a sense of what the pattern was. Once we had gathered as much information as we could about the outside, we knew we had to try and get inside the offices during business hours to see if there were any security measures. The strategy was to have me pose as a Swarthmore College student and interview the head of the office about opportunities for women in the FBI.

I was given an appointment and had to disguise my appearance as much as I could. I had enough time in the office to get a good sense of its layout, and I was relieved that there were no security measures at all—no security devices or alarms, no locks on the file cabinets. That was the information that we needed to make the plan seem feasible.

JR: We chose March 8—the night of the world heavyweight fight between Muhammad Ali and Joe Frazier—because we figured every- one would be distracted, and the cops wouldn’t be as vigorous with their patrolling. That turned out to be the case.

After we got in and got the files, we sorted them into criminal files and political files. We sent those political files to three newspapers and two politicians. Everyone sent the files immediately back to the FBI, except for The Washington Post. Its story ran on the front page on March 24, 1971. After that, editorials began to appear in The New York Times and The Philadelphia Inquirer, and the whole thing blew up right in Hoover’s face. He sent out 200 agents to find us and kept screaming, “Find me that woman!” because they figured out they had been cased.

THAT WAS THE FIRST STEP IN BRINGING DOWN HOOVER’S HOUSE OF CARDS?

JR: That’s a good way of putting it, a house of cards. It was the first card to go, but there would have to be others. One of the documents we found said COINTELPRO [Counter Intelligence Program], but we had no idea what that was. Then in 1973, Carl Stern, an NBC investigative reporter, looked into it. Stern was able to find out that COINTELPRO was a series of tricks which included the FBI’s participation in the assassination of Fred Hampton, the head of the Black Panther Party in Chicago, and character attacks against actress Jean Seberg—a Black Panthers supporter—which eventually led to her suicide. [Hoover] had been head of the FBI for almost five decades and had turned it into a national, secret police force. That’s what we were able to uncover, and that was pretty important.

ALI, WHEN YOU WERE WORKING ON YOUR STORY, DID YOU HAVE A SENSE OF WHAT YOU WERE ABOUT TO UNCOVER?

Ali Watkins (AW): I got the original tip in January 2014, and I’d been covering national security at McClatchy for about eight months at that point. I was used to the “no comments” and people being closed off, but as soon as I started asking this line of questioning, they shut off in a completely different way. That was a very good indicator to me that this was not your typical national- security story. I had never touched on some- thing that people had been so afraid of.

People who used to talk to me were now telling me, “I don’t need to be seen with you.” It was very apparent right off the bat that we were pursuing a line of questioning they didn’t want us to ask.

We figured out there was alleged monitoring of the computers, and then we found out about the staff taking documents. Beyond that, you have what’s in these 6,300 pages: the rendition, detention and interrogation program, classified as torture by many. There were all these different pieces to this puzzle, and it took us about two months before we realized what they all were.

WAS IT FRUSTRATING NOT TO BE ABLE TO TALK TO YOUR SOURCES ONCE THIS STARTED COMING OUT?

AW: It was, but [it was] also exciting from the perspective that I was a 22-year-old college senior who had the opportunity to work on a story like this. It was an incredible learning experience, and an exciting part was thinking on your feet constantly and finding a different way to ask the question.

HOW WERE YOU ABLE TO CULTIVATE SUCH STRONG RELATIONSHIPS WITH YOUR SOURCES SO QUICKLY?

AW: A lot of my time was spent in the hallway of the Hart Senate Office Building, outside the Senate Intelligence Committee doors. I reported from there because not many other reporters hung out there. I had longer time alone with the senators.

The Hill is like a giant game of tag; senators get to decide what is “base.” The elevators are base and their chambers are base, so you only have about 10 feet to get them to talk to you. Outside the Intelligence Committee’s hearing room, they had a 200-foot walk to the elevator as opposed to that 10-foot stretch, so I started hanging out in that hall- way more [often] because I wanted the extra few feet to ask them questions. I think people who see value in journal- ism saw I wasn’t afraid to wait hours just to get that extra 200 feet. I think it was a matter of being there and showing that I would do anything I needed to do.

WERE YOU CONCERNED ABOUT THE FALLOUT OVER THESE SITUATIONS?

JR: J. Edgar Hoover sent out 200 agents to try and find us. The reason they didn’t is because Philadelphia in the late ’60s and early ’70s was the national center in terms of people protesting the Vietnam War. So when the FBI had no physical evidence from the robbery site, it was faced with the insurmountable task of sorting through thousands of names [for possible suspects]. The resistance movement in Philadelphia allowed us to hide in the best possible place, which was in plain sight.

BR: It seemed that the only way we could get documentation in a nonviolent way was to take action as regular citizens because there were threats to democracy that we felt we needed to stand up and do something about. We felt compelled to take action. We knew the risk, we knew the jeopardy, but we were not reckless. We were very careful and meticulous about our planning.

AW: I think it is really interesting to look at our different roles, because [the Raineses] had possibility of criminal prosecution. I was very lucky to have the kind of guidance I did. My colleagues made sure I had the necessary legal protections.

I was more concerned for the people I was pursuing for information. Even if they didn’t talk to me, the fact that my number would show up on their phone could have raised suspicions. So the way we pursued the story was a lot of old-school, boots-on-the-ground journalistic work: showing up, waiting around and being present.

DO YOU SEE SIMILARITIES IN THE SITUATION TODAY IN WASHINGTON, D.C., AS COMPARED TO 40 YEARS AGO?

BR: There were serious threats to democracy and to people’s rights in 1971. The Vietnam War was escalating and the government was not truthful about it with the U.S. population, but it wasn’t on today’s scale. I think what is happening today is once again happening in secret and is violating people’s rights to privacy. All the tactics now being used to gather information in the name of fighting terrorism are much more destructive. Except for this vague notion of “We are protecting you from terrorism,” there is no rationale for why personal information is being gathered, how it is stored and how it is used, and most people are acquiescing to it.

JR: The situation 40 years ago, in terms of permissible national discourse and the situation today are very similar. Then you could have your political career ended just like that if they could nail you for appearing soft on communism, and of course it was Joe McCarthy and Hoover who used their very powerful institutions to say who was “un-American.” That muzzled folks in Washington. Today you have a different ideology, but its function is the same: You can’t be soft on terrorism. Every politician in Washington, including the president, is terrified if the power of the NSA and the CIA is restricted and then there is another attack, then their parties—their political lives—are over. Today Washington is run by fear—just like it was back in 1971.

HOW DO EIGHT PEOPLE KEEP SUCH A HUGE SECRET FOR 40 YEARS?

JR: Our necks were on the line. We weren’t Don Quixote; we weren’t into some kind of martyrdom—we were into being effective agents at getting information to the press.

WERE YOU AFRAID YOU’D BE CAUGHT?

BR: We didn’t realize it at the time, but the FBI had a sketch of me as I looked when I went to the office, and they were circulating it. But as time went by, they turned their focus on a group of 28 people who had broken into a draft board in Camden [New Jersey]—I think the FBI was convinced that somewhere among them were the Media folks.

JR: We did have a real problem when the ninth person on our team dropped out of the action maybe three weeks before. A couple weeks after the action he said he was thinking of turning us in. When I asked why, he indicated that his girlfriend had said parts of the files were very defense- sensitive and identified missile sites around Philadelphia. There was no truth to that, so I asked him how long he’d known this girlfriend. He said a few months, and I asked him if it had occurred to him that she might be working for the FBI. It had not, and I invited him back to the house a few weeks later to help paint the kitchen. We re- cemented our relationship that day, and he never busted us.

ALI, WHAT IS YOUR HOPE WHEN THE ENTIRET Y OF YOUR REPORTING COMES TO LIGHT?

AW: I’m never totally sure how to answer that question. It’s not my job to have an opinion. The outcome, the political hardball that’s played over this—I just report on it. I will say that if there is one thing that I really hope comes out of this is that light is finally shed on something that a lot of people in Washington have continued to let go unexposed. If there’s one thing I hope this story does, [it] is restore that balance of power between the executive and legislative branches—and that’s not my interpretation, that’s lawmakers and U.S. officials saying it’s off.

WOULD IT BE ACCURATE TO SAY THAT JOURNALISM IS A FORM OF ACTIVISM?

AW: I think activism has a subjective connotation, and old-school journalism—that of the Woodwards and the Bernsteins—strives for objectivity. I do think that journalism is a vehicle for change, and the watchdog function is the most encouraging part of being a journalist. So if you consider watchdog journalism to be a form of activism, then I guess you can call it that. But I think journalism has one obligation: to the truth.

JR: [Washington Post editors] Ben Vandicken and Ben Bradlee felt our story was an important national story, and they ran it at great risk to their own organization’s economic interest. Our story would have gone nowhere without the Post. The watch- dog function is crucial, because power will always try to hide its most important decisions from supervision.

BR: In the case of [former NSA contractor Edward] Snowden’s whistleblowing, it took two or three very courageous journalists to bring that story to light. If certain government agencies and institutions operate behind closed doors, it becomes difficult to finally get to the truth. But in a democracy, you can’t have that kind of secret activity going on. The people are the arbiters of what is right and what is wrong.

*Bonnie Raines' interview was conducted separately. The questions posed to her were identical to those presented to John Raines and Ali Watkins, who together met with the writer.