In the Land of Poison and Fire

My train pulls into Naples, Italy, at 9 a.m. After dodging pickpockets in the station, I hop in a cab and am whisked at a ridiculous speed through the city’s congested, labyrinthine streets. Naples is a monument to tragically squandered potential: At first glance, it appears to comprise the worst aspects of urban blight in the U.S. But beneath the gross neglect, vandalism and overdevelopment is the ghost

of a beautiful city.

Naples is older than Rome. It is home to exceptional works of art, from Sanmartino’s “Veiled Christ” to Caravaggio’s “Seven Works of Mercy.” The pizza more than lives up to the legend. But Naples is like that guy who is a really great person at heart, he just spends too much time running with the wrong crowd.

I’m dropped off in front of a palazzo in a complex far above the city center. That is where Antonio Giordano, a pathologist, professor of biology, and director of the Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine at Temple, spends a third of his year. His house has a hillside view of Capri, Mount Vesuvius, the Gulf of Naples and, off to the left, the city itself. It’s positively stunning, and no doubt helps shape Giordano’s unique perspective on the city that raised him, the city he has dedicated a portion of his life to saving.

“Naples is a city that you love or hate,” he says as we drink Campari on his terrace. “There’s no in between.”

An Unlikely Inheritance

Giordano graduated summa cum laude from the University of Naples with an MD and a PhD in pathology, then relocated to the U.S. in 1986. In this, we have some common ground—I left Philadelphia for Rome seven years ago. One of the universal qualities of the expat is the sense that your body houses two identities, one for your home and one for your adopted country.

“When I’m there I want to be here,” he says, “and when I’m here I want to be there. I love Italy for the culture, the atmosphere. I love America for its drive.”

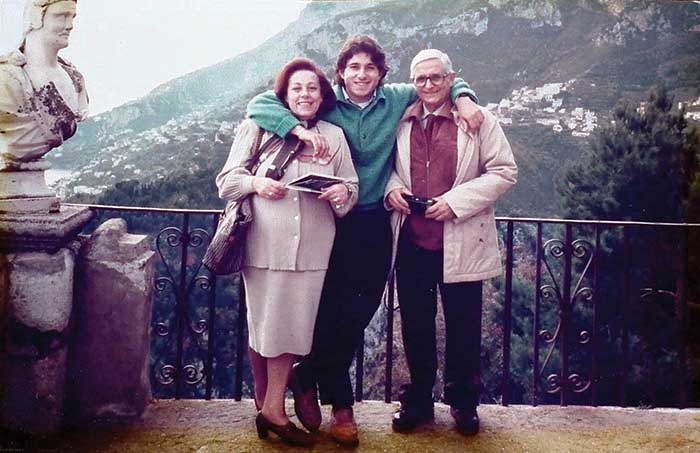

Giordano is the first in his family to emigrate to the U.S., but the drive he feels there is hereditary. His father, Giovan Giacomo Giordano, was a noted cancer pathologist at both the Second University of Naples and the “Pascale” National Cancer Institute of Naples. In the 1970s he published “Salute e Ambiente in Campania” (“Health and Environment in Campania”), a white paper that first detailed the link between unregulated industry and that area’s rising cancer rates.

“My father was an introverted man from a solid family who loved science in his own pure way,” Antonio Giordano says, handing me a copy of the report. “But 80 percent of my success is due to my mother.” Maria Teresa Sgambati-Giordano is from a fairly affluent family and accustomed to playing host and massaging personalities. The marriage of his parents’ temperaments meant Giordano grew up in a house where Nobel Prize winners were often guests.

The passion and dedication he inherited from his father drive Giordano scientifically, but when he arrived in the U.S. and found himself in competition with Ivy League–connected alumni for funding, it was his in-herited social graces that landed him a grant.

Early in his career Giordano did research on the cell-division cycle at Long Island’s Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, whose director was Nobel laureate James Watson (known as the “father of genetics” for his role in discovering the structure of DNA). During a conversation in which Giordano complained about the cronyism that often directs grant money in the U.S., Watson asked which part of Italy he was from.

“Too bad you don’t come from Milan,” Watson replied when Giordano said he was from Naples, meaning that Milan was a much richer city and would have been an invaluable resource, could Giordano claim some connection.

But his Naples birthright did pan out. A few years after his conversation with Watson, Giordano met fellow Neapolitan expat Mario Sbarro, then CEO of the eponymously named pizza franchise found in every airport, truck stop and college campus on the East Coast. The introduction came about through Giordano’s wife, Mina Massaro-Giordano, a Long Island native and Sbarro’s neighbor.

When Giordano later relocated to Philadelphia to do cancer research at Temple and then Thomas Jefferson University, he made regular trips to New York to visit Sbarro. Every Sunday, he and the older man would go for a walk, during which Giordano would narrate his predicament: He was beginning to do important work, but it was hard for young researchers to get funding, and academia often delayed programs due to financial limitations and internal politics. He wanted to launch an organization that would grant scientists in his field independence in terms of funding and freedom from academic structure. All he needed was the startup cash.

After a year, in 1993, Sbarro agreed to donate $1 million out of pocket. The Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine was born.

In the 21 years since, the institute has yielded impressive results. It’s No. 2 in cellcycle research publications (the cell cycle is the process by which a cell grows and divides to create a copy of itself) and has more than 30,000 scientific citations to its credit. Giordano also has discovered a tumor-suppressor gene and other proteins that regulate cell growth and the cell cycle.

“Our research was a very important piece of a puzzle that is behind the major success stories in the diagnosis and treatment of cancer,” he says. “It’s nice to see that we’re making a contribution to the field of curing or battling the disease in general.” Which brings us around to the reason for my visit.

The Land of Tumors

Naples is sick. Campania, a southern region of Italy of which Naples is the capital, is in the midst of an epidemic. In the last two decades, the number of reported tumors has risen by 40 percent in women and 47 percent in men. The “Pascale” National Cancer Institute of Naples in 2012 reported that 47 percent more people are stricken with cancer in Naples than anywhere else on the Italian peninsula. In Acerra, a small Campania town with only 56,000 residents, three children have brain tumors at any given time (as opposed to the national average of 0.5 per 100,000 children).

Once referred to as Campania Felix (Prosperous Campania) by the ancient Romans, the Italian government has taken to calling the region la terra di tumori—“the land of tumors.” Journalists toss around the phrase “triangle of death” (coined by The Lancet Oncology in 2004) in reference to the land between Acerra, Nola and Marigliano, three Campanian towns. Prior to our interview, Giordano told me in text messages that he was looking forward to my visit to “the Land of Poison and Fire.” Italians might have a flair for the dramatic, but in this case, it is warranted.

What is at the root of the Neapolitan health crisis? In articles written on the topic in the last 10 years, if the word “Camorra” isn’t in the headline, it will be in the opening paragraph. The Camorra are the Campanian version of the Mafia and one of Italy’s three major crime syndicates; the group dates back to the 18th century.

“It’s an organization that is both entrepreneurial and criminal,” says Roberto Saviano, author of Gomorrah, in the 2008 Vice magazine documentary Toxic: Napoli. During northern Italy’s industrial boom in the 1980s and ’90s, the Camorra discovered the lucrative business of illegal waste disposal.

Safely and legally disposing of waste is costly. The Camorra offered manufacturers and refineries an alternative: They would dispose of the waste at a fraction of the rate charged by specialist companies. The Camorra then dumped harmful chemicals in fields, caves, quarries and even the Bay of Naples. Depending on the substance, the Camorra might burn it, mix it with soil and spread it over the land, or bury entire containers. Current estimates indicate that more than 10 million tons of illegal garbage have been dumped in the area over the past 20 years.

But the truth did not stay buried with the toxic waste. In recently declassified testimony given in 1997, Carmine Schiavone—a former Camorra treasurer turned informant—described the location of many of the dump sites in the Triangle of Death. Schiavone, who had personally ordered more than 50 executions during his career with a powerful Camorra family, claimed that the secret of the contamination was too much for even a Mafia boss like himself to bear, as the people who lived in the area would be “dying of cancer within 20 years.”

But if you ask Giordano, the mob is merely a symptom.

“You can blame Camorra if you want. It makes for an exciting headline. But my father always thought the real problem was politicians.” He shows me a circular chart he has made that depicts interlocking thirds of Camorra, politico (politicians) and imprenditore (entrepreneurs).

“The major carcinogenic chemicals that were known all over the world to be killers for human health were completely ignored by the Italian government,” Giordano says. “They never put any controls on the industry. Why? Because they were feeding the industry. They were getting a kickback. It was just a loop of favors they were sharing with the involvement of the Camorra.”

Stop ‘Biocido’

So what’s the solution to what the Italians call biocido, or the killers of life? According to Giordano, the only thing that will give the Italian government the incentive to fix the crisis is international embarrassment.

“We need major exposure internationally to be sure these environmental disasters are monitored. It needs to become a worldwide scandal, showing that Italy, a beautiful country, is in a destructive position.”

Giordano has satellite laboratories in Siena and Avellino, but he maintains that the real war is being waged in Philadelphia. As Giordano’s reputation at Temple grows, he’s able to direct international attention to what was once a localized problem.

Giordano believes his role is also to educate Temple students—the next medical generation—about the importance of independent research. “The research should benefit humankind,” he says. “It should benefit citizens. This is not happening because the research is controlled and influenced.”

More than anything, he wants his students to understand that in the current financial climate, science must include a component of creativity. Just as he pursued and secured the funding that allowed him to create the Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine more than 20 years ago, they, too, will need to be both diligent and innovative.

It’s almost noon. Giordano excuses himself for a lunch engagement, one of the networking sessions that increasingly displace his own time in the labs. The last thing I see as my train leaves Naples is graffiti spray-painted on a dilapidated shack on the outskirts of the city.

It reads, “STOP BIOCIDO.”