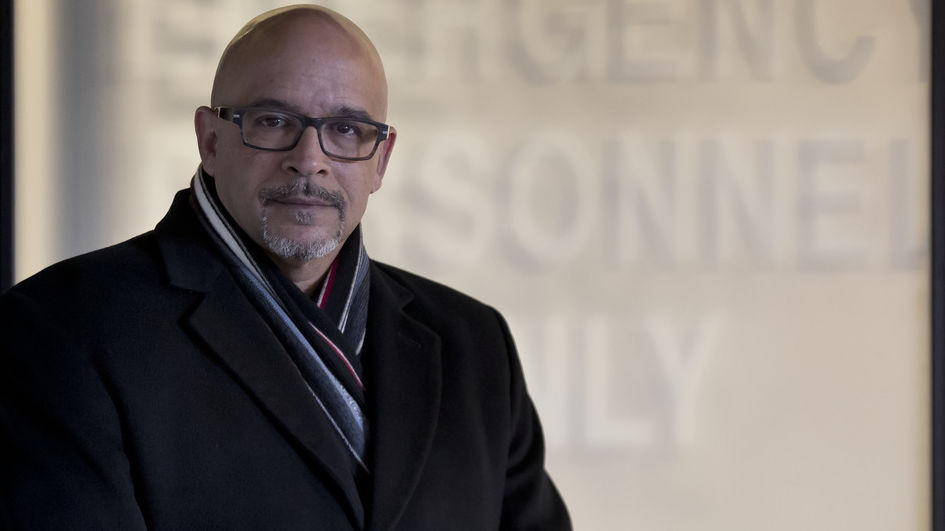

Temple’s Scott Charles on gun violence prevention

The trauma outreach manager at Temple University Hospital joined local and regional business leaders to discuss the impact of firearms incidents on economic growth in Philadelphia.

Addressing victim trauma may be a key to ending gun violence.

That’s according to Scott Charles, trauma outreach manager at Temple University Hospital, who oversees the hospital’s violence prevention and intervention initiatives. For nearly two decades, Charles has worked on the front lines of a national public health crisis that claims 38,000 U.S. lives each year. Charles’ work with Amy J. Goldberg, interim dean at Temple’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine, has been featured nationally on NBC’s The Today Show, ABC’s World News Tonight, NPR’s Morning Edition and the feature-length documentary Number One with a Bullet.

Recently Charles was invited to speak at a special event, sponsored by the Chamber of Commerce for Greater Philadelphia, focusing on the impact of gun violence on the city’s commercial corridors.

For “Addressing Gun Violence & Inclusive Business Growth: A Roadmap for Growth Issue Forum,” the chamber convened a panel of experts to discuss ways our regional business community can confront issues, such as fears for personal safety, stifled business growth and negative perceptions of the city.

In addition to Charles, the panel, moderated by Sara Lomax-Reese, president and CEO of WURD Radio, included Donna L. Allie, president and CEO of Team Clean, Inc.; Harry Hayman, manager of Bynum Hospitality Group; Jabari Jones, president of the West Philadelphia Corridor Collaborative; and Gregory Reaves, principal at Mosaic Development Partners.

The need for this discussion is clear, explained Lomax-Reese as she introduced the panel. “The issue of gun violence in Philadelphia is multifactorial, spanning every aspect of our society—education, healthcare, politics—but today we are talking specifically about the economic impact on neighborhood corridors and businesses […] and how that impacts the city as a whole,” she said. “The impacts of gun violence are not confined to any one area in our city: We’re all in this together.”

Underscoring how violence can negatively impact economic growth, Jones noted that commercial venues in Center City enjoy three to five more hours of revenue every day than similar businesses in neighborhoods that close early due to safety concerns.

“That can equal out to 25 extra hours per week—if you use a conservative estimate of $200 per hour that these businesses are making in profit, then that’s an extra $5,000 per week that businesses in Center City make over those in neighborhoods where the commercial corridors completely shut down,” Jones said. “How can we shift that opportunity so that these businesses are not at such a deficit when the sun goes down?”

Another problem, pointed out Lomax-Reese, is that according to the Pew Charitable Trust, only 2.5% of the businesses in Philadelphia are owned by Black people.

That’s a problem, explained Reaves, because Black businesses are likely to hire Black people. “If we’re not investing in those businesses, we’re not going to have Black people in those ecosystems.”

Reaves also offered another statistic: If we are able to reduce gun violence by just 25%, it will increase real estate values across the region by more than 2%. Which means, Reaves emphasized, that the reduction doesn’t just help people in those neighborhoods experiencing violence directly, it helps all people in all neighborhoods.

Finally, the panelists looked to Charles for insight into the complex causes of gun violence. In his role at Temple University Hospital, Charles sees the lasting impact of trauma not only on patients who are victims of gun violence but also on the surrounding communities.

“I think it’s great to talk about a deficit of investment, but I think more than anything, what we see at the individual level is a deficit of hope,” said Charles. “And that is a direct byproduct of the austere conditions that these young people are living in.”

Charles explained that the last time Philadelphia experienced the number of gun violence incidents that it is now seeing—in part due to restrictions created by the pandemic—was in 2006. But, said Charles, when the violence declined in subsequent years, “we didn’t really address the collective trauma that the city experienced, or the individual trauma that the children were experiencing who were bearing witness to this violence.”

“With those kids who were 5 years old, we really didn’t do much of anything. And we didn’t look at their emotional needs or psychological needs or social needs, and we just kind of went about our business,” he said. “Well, those guys are 20 or 21 years old now, and they’re the individuals we’re seeing in our trauma bays—the individuals I’m talking to at the bedsides.”

Charles told attendees he hopes we won’t make that mistake again.

Learn more about Charles and Temple University Hospital’s efforts to prevent firearm injury.