A WWII veteran’s fight to receive an honorable discharge

After Nelson Henry Jr. was given a discriminatory “blue discharge” because he was African American, it took nearly 75 years to right the wrong.

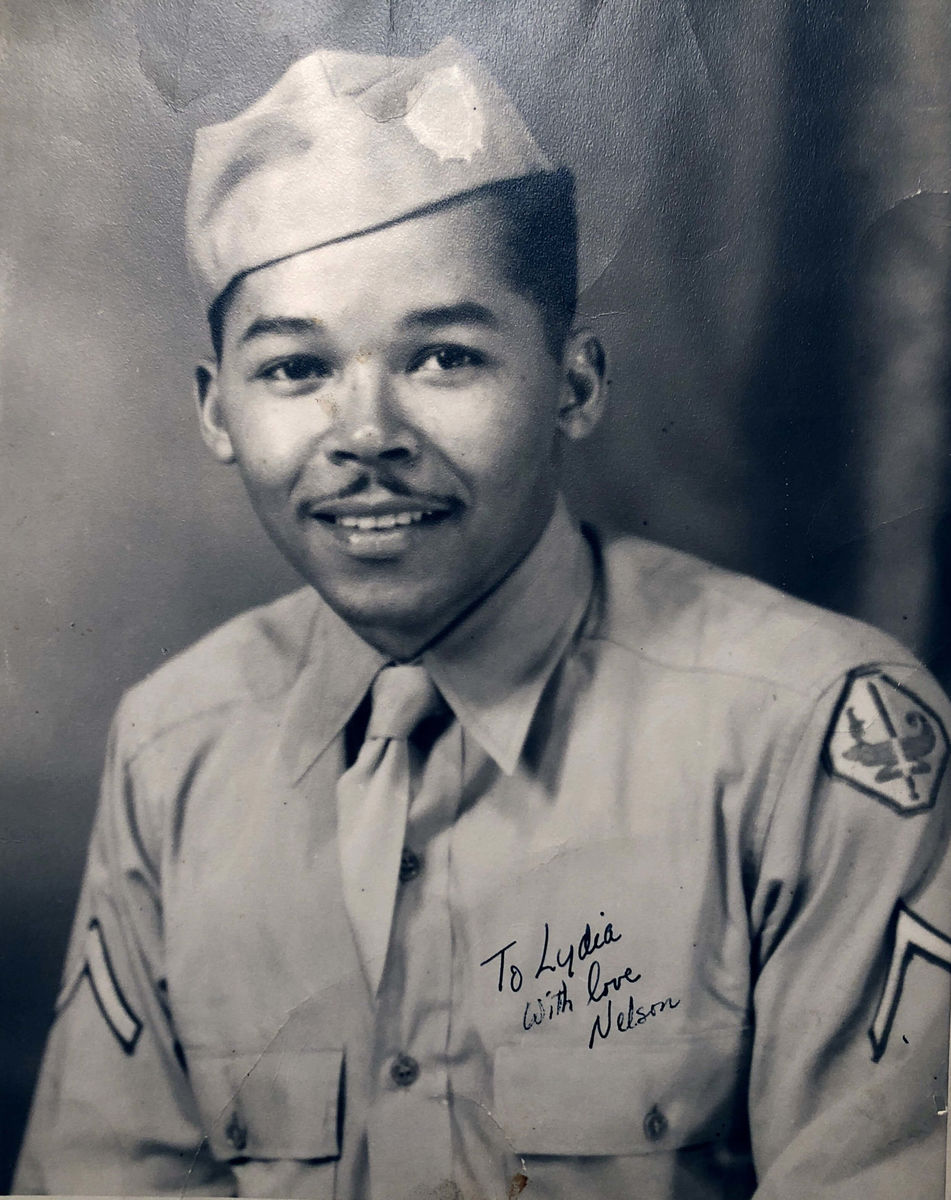

When World War II veteran Nelson Henry Jr., CLA ’69, was released from the Army in 1945, he was given a “blue discharge,” one of thousands of soldiers targeted because of their sexual orientation or the color of their skin. It would take nearly 75 years to right that wrong.

Henry was a sophomore at Lincoln University when he enlisted in 1942 and was selected for the Army Specialized Training Program: a course created to meet the wartime demand for soldiers with technical skills, including engineering and medicine.

The program was cut short though and Henry was sent to a segregated unit in the South. But when the war ended and his unit was assigned clean up duty in the Pacific, Henry couldn’t go.

“He couldn't pass the physical, even though he was an athlete,” said Nelson Kent Henry, MED ’76, Henry’s son. “They wanted him to put a heavy pack on his back and go into a squat and bounce up. And he couldn’t do that without pushing off with his hands, because his knees had been injured in the first two years of college at Lincoln, playing football.”

Henry had passed his initial physical to join the Army and his knee injuries were part of his medical history. But the injuries had worsened during training and he couldn’t pass the second physical and go overseas.

Seeing no further use for him, his superior officers discharged him. “But it wasn't a dishonorable discharge and it wasn't an honorable discharge,” Nelson said. “It was a blue discharge, which he knew had a stigma associated with it.”

Nelson Henry Jr. enlisted in the Army in 1942. (Photo courtesy of the Henry family.)

Between 1941 and 1945, more than 48,000 soldiers—many of them Black or LGBTQIA+—were given a blue discharge. Named after the blue paper they were printed on, the discharges routinely denied veterans benefits—including the G.I. Bill, which many used to attend college—and the right to have an honor guard at their funeral. It also left a stain on veterans’ records that discouraged employers from hiring them.

The Army eventually replaced blue discharges in 1947 with two new classes: general and undesirable.

At the time, Henry didn’t realize the full impact his blue discharge would have on his life. “He didn’t know all the ramifications,” said Rosemarie Henry, MED ’76, Nelson’s wife. “He just knew that it was kind of a nebulous zone.”

Back in Philadelphia, he set his dreams of becoming a dentist aside. “He needed money fast for the support of the family and he saw it was going to be a long road to finish up dentistry,” Nelson said. Henry enrolled in night classes at Temple, with the goal of getting a sociology degree and a job at the Pennsylvania State Employment Office. He’d barely started when the university informed him he wasn’t receiving veterans’ benefits.

Henry dropped out of Temple and worked various jobs, including driving a cab. He eventually re-enrolled at the university a decade later, studying part time. “My husband and I were dating in high school,” Rosemarie said. “And I remember many times his parents had invited me over for dinner, and we would be there, but Dad [Henry] was always upstairs studying.”

It took Henry 13 years to earn a bachelor’s in psychology. “It seemed like a long time, because he was working full time and going to school at night,” Nelson said. “But I'll never forget: He got his degree three years before I got mine.” Henry went to work at the state employment office as he’d originally hoped, eventually becoming a manager there.

Nelson got a mechanical engineering degree at Drexel University, while Rosemarie was an undergraduate at Temple with a concentration in biology. They ended up in the same class at the Lewis Katz School of Medicine and both graduated in 1976.

Henry rarely talked about his military service. “It was a source of pain,” Nelson said. The blue discharge had changed the course of his life. “Everything temporarily halted. There was no school, no professional job all that period of time.”

Nelson only found out about the possibility of upgrading his father’s discharge recently, when his brother Dean began to look into how Henry had left the Army. Dean got in touch with Elizabeth Kristen, an attorney at the nonprofit Legal Aid at Work, who connected him and Henry with Dan Devoy, director of the Golden Gate University School of Law’s Veterans Legal Advocacy Center.

Henry had tried to get his discharge upgraded to an honorable one and his benefits restored several times. Now in his 90s, he tried again. In 2019, with the support of Pennsylvania Sens. Bob Casey and Pat Toomey and coverage in the Philadelphia Inquirer, he succeeded.

“He said it was one of the happiest days of his life and he only wished that my mother had been around to see it,” Nelson said. Lydia Henry died in 2016.

Henry died on May 9, 2020, of complications caused by the coronavirus. He was 96. His family is proud of him and his achievements. Despite everything he faced, he kept going. “He never gave up,” Nelson said.

—Edirin Oputu