Lewis Katz, CST ’63: In the business of making memories

Lewis Katz had a pull. Some likened it to gravity, others to a magnet. His family and his friends—a tremendous sphere, from presidents and superstar athletes to grade-school classmates and coffee-shop cashiers—he pulled close. Those needing a lift—of hope, of a way out of hardship—he pulled up.

Four days after Katz and six others were killed in a plane crash, the Temple University community pulled together for a memorial service June 4 with the stature, passion and vibrancy befitting a man who has given so much.

“He left the magnetic field. It’s still here. That’s why we’re here,” former President Bill Clinton said. “We can’t walk away from the reality that is still here. And some day, you’ll hear him saying, ‘We can do this. Come on, say you’ll do it. We’ll have such a good time trying.’ So thank you, Lew Katz, for what you did for me, for never giving up in the darkest hour, for making sure that we had a good time trying.”

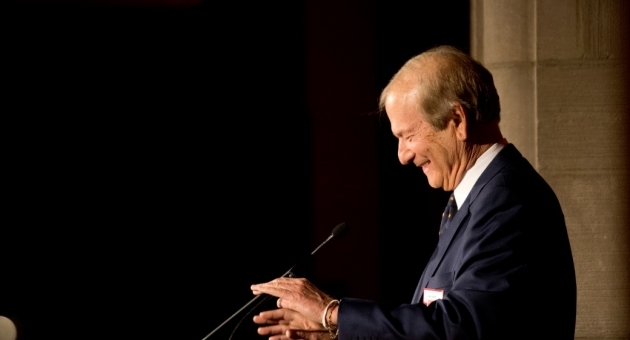

An estimated 1,400 people attended the public service, held in the Temple Performing Arts Center and simulcast in Mitten Hall. Fifteen speakers combined their memories “to create a comprehensive image of this remarkable man,” as Temple President Neil D. Theobald said in his opening remarks.

What an image it was.

A man as comfortable playing Nerf basketball with Clinton and former Pennsylvania Gov. Ed Rendell as he was leaving an exorbitant tip in appreciation of a hardworking college student waiting his table at a diner.

A man as quick to publicly support a major cause or institution in which he was passionate—opening charter schools in his native Camden, New Jersey, or serving the Boys & Girls Clubs of America—as he was to extend a spontaneous act of kindness, often anonymously.

A man who, in the words of U.S. Sen. Cory Booker, saw “the divinity not in kings and queens and presidents and senators but to be able to look on every single person, black or white, Christian or Jewish. He seemed to be drawn to those who had faced the most difficult path.”

“This is what I loved about him,” Booker continued. “Whether it was a child born to difficult circumstances in Camden or someone he met on a grocery store checkout line, he saw their dignity and their worth, and he elevated it even higher.”

Philadelphia Inquirer editor Bill Marimow called Katz “a man in motion,” unsurpassed in his passion and compassion. Author and historian Doris Kearns Goodwin, whose Massachusetts home Katz visited before he died, said he maintained boyish “vitality, enthusiasm, joy, playfulness, curiosity and, above all, a sense of wonder about life itself.”

Katz was the best man at the wedding of Comcast-Spectacor Chairman Ed Snider, one of his closest friends. Snider said simply: “He was the best man because he’s the best man I’ve ever known.”

Katz’s crown jewels: his son, Drew; his daughter, Melissa; and his grandchildren, including teenager Ethan Silver, whose poised remarks drew a standing ovation.

Drew Katz, the service’s final speaker, illustrated the lengths to which his father would go to make indelible memories for those around him. For Ethan, it was Katz arranging for him to serve as a ballboy for NBA All-Star LeBron James, take a swimming lesson from Olympian Michael Phelps, play baseball with big leaguer Chase Utley, hit tennis balls with Novak Djokovic and catch a touchdown pass from NFL quarterback Andrew Luck.

Of all the titles Katz held, friend, father and grandfather were his most cherished. And of all his professional triumphs, Drew Katz said, “My Dad’s best business success was in the business of making memories.”

That message was emphasized throughout the day, starting with Theobald, who recalled seeing Katz and his granddaughters together at the dinner for honorary degree recipients on May 14. Katz was beaming as he spoke, not because he was getting an honorary doctorate, but because his grandchildren were there to celebrate with him.

“Work matters,” Theobald recalled, citing Katz’s Commencement address a day later. “Family matters more.”