Rapid Response

<div>When an Amtrak train derailed near Temple University Hospital, the staff garnered national praise for treating the greatest number—and the most severely injured—of victims. Here's how they did it.</div>

Photography By:

Joseph V. Labolito

Story by:

Theresa Everline

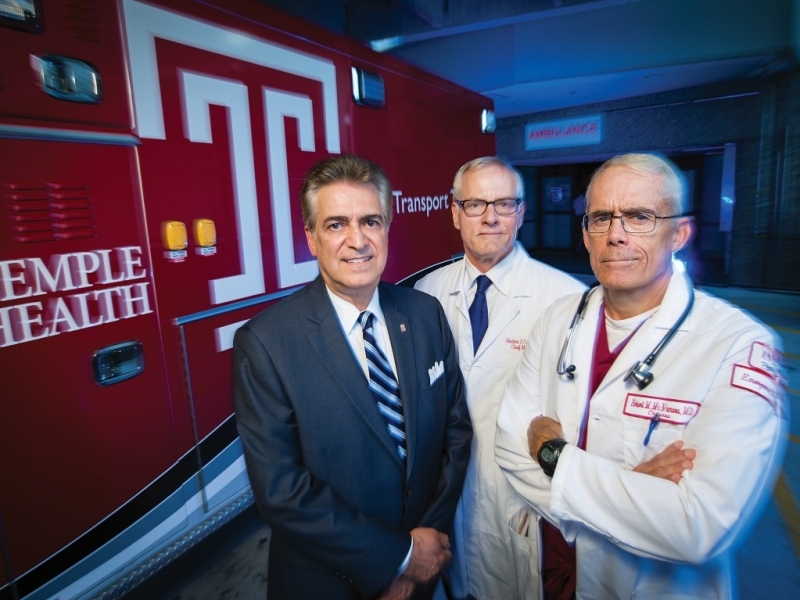

Temple University Hospital staff, including (from left) John Kastanis, president and chief executive officer; Herbert Cushing, chief medical officer; and Robert McNamara, department chair

of emergency medicine, go through regular, rigorous training exercises that prepare them for mass-casualty events like the Amtrak derailment.

At 9:39 p.m. on May 12, every bed in the emergency department was full.

For Temple University Hospital, which has the busiest emergency department in the Delaware Valley, that situation isn’t remarkable. But at 9:40, what had been a typically fast-paced workflow transformed into a highalert surge when a call came in: Amtrak Train 188 had derailed in Philadelphia’s Port Richmond neighborhood. Three miles west, Temple was the closest trauma center to the crash site. And at 9:57, the first patient came through the hospital’s doors.

“We didn’t have good information from the site to know how bad it was,” says Herbert Cushing, Temple’s chief medical officer. “The police and firefighters who scooped up patients and brought them here mostly didn’t linger around to tell us what they were seeing.”

What the hospital staff would end up doing in response to a tragedy that injured more than 200 people and killed eight was treating more victims than any other Philadelphia area

hospital. Temple University Hospital’s main Health Sciences Center location received 54 people and its Episcopal campus an additional 10 in a matter of only hours—on a night that began with no available beds.

Years of preparing for crises made Temple ready to spring into action, and Wes Light, FOX ’10, ’14, is the person in charge of planning for the worst. “I’m paid to worry,” Light says.

As the hospital’s manager of emergency preparedness, he assesses the greatest threats. Six times per year, he presents terrible scenarios to the administrators and asks, “What

would you do?” Those exercises on paper supplement regular mass-casualty training courses and exercises using fake patients.

Sometimes worries about what might go wrong at a site of life-or-death realities come from unexpected places. For example, Cushing made a decision on the morning of the crash that proved prescient. Regular maintenance on the main hospital’s electrical substations had been planned for every night that week. On Monday, when two substations were taken down, “some areas didn’t go onto the emergency generator power,” Cushing says.

Though nothing bad occurred, Cushing woke up early on Tuesday, May 12, and fretted over the substations scheduled to go down that evening: They fed the ER, the operating rooms and radiology. “The big three,” Cushing notes. He had no way of knowing that 54 patients and hundreds of others would be surging into those exact areas that night, but he couldn’t shake his discomfort. He called off the maintenance.

NEEDED REINFORCEMENTS

Temple’s medical staff members who were on duty that night were highly prepared, but their numbers weren’t sufficient. Dozens of people were called in to help, including Dara Delcollo, who, despite her 10 years as a nurse at Temple, was still amazed when she arrived: “Just looking out and seeing everyone covered in soot, with tags hanging from their arms for their triage level—I never saw anything like that before.”

Each trauma patient requires an emergency-room physician, a trauma surgeon, several nurses, an anesthesiologist and others.

As a crisis develops, its enemy is the unknown. How bad will the injuries be? Are numerous people trapped who will create a second wave of patients? Nurse Sheila Last was on the front line most of the night, helping evaluate victims’ injury levels. “Every 20 minutes, there were four or five police wagons dropping people off,” she recalls. “The first 20 or 30 people were not assessed by the fire department on the scene, so we would open the doors and didn’t know what to expect.”

Nonetheless, the staff met the challenges with amazing efficiency. Medical student Peter Tomaselli, Class of 2016, helped track the arrivals. Watching the staff skillfully respond “was both humbling and inspirational,” he says. “The trauma surgery team was particularly impressive, and they were aided by residents and attending physicians from other surgical departments. It was truly a team effort on a grand scale.”

Twenty-three of the patients at Temple that night were classified as “traumas,” the worst injury level. “One of these kinds of patients is very resource-intensive,” explains Light, the emergency-preparedness manager. Each trauma patient requires an emergencyroom physician, a trauma surgeon, several nurses, an anesthesiologist and others. “To have 23 of them in a short amount of time takes a lot,” Light observes with remarkable understatement.

John Kastanis, the hospital’s president and chief executive officer, was in the emergency department after the crash. It might have looked like chaos to an outsider, but he says the doctors, nurses and ancillary staff were all executing their roles exactly as they had practiced. “While events such as this are thankfully rare, it is our duty to protect potential future victims by fully preparing for whenever they might occur. This is what we train for.”

Danielle Claire Thor, Class of 2016, director of the student-run Temple University Emergency Medical Services, usually responds to Main Campus incidents. She and her team headed north on Broad Street once they heard about the catastrophe. “Based on previous experiences, I thought we’d be there all night, until 8 or 9 in the morning,” she says. But she was able to leave after only four hours. “One of the best indicators of how smoothly it went was how quickly it got done.”

Of course, a hospital doesn’t run on nurses and doctors alone. The first people Cushing mentions when he talks about the event are “the cleaning folks, the security folks, the people in the blood bank, the lab people. Without the radiology technicians, we wouldn’t have been able to do all the CAT scans really fast.”

Joseph Moleski, director of hospitality and nutrition services, has developed a mindset unique in the food-service industry. “I was at home starting to doze off when my wife came in and turned on the TV,” he says. “I saw it on CNN and said, ‘I have to go to work.’” The hospital staff, the relatives of the victims, the first responders flooded with adrenaline,

the members of the media—they would all need to eat. It was the largest disaster Moleski has encountered in his four years on the job, but he and two other workers held down the

fort, brewing pots of coffee and distributing premade sandwiches. “One guy just kept making pizzas,” Moleski remembers.

The night had its emotional moments for Moleski when he encountered anguished family members. Ultimately, he says, “I felt proud to be a part of it. It was a well-oiled machine.”

MANAGING MANY NEEDS

Wes Light tries to imagine every contingency, but no major crisis follows a script. Some of what had to be managed never appears in emergency-room TV dramas.

All those beds that were already full? An alternate care site was established, and patients who were ready were discharged—“which is kind of difficult in the middle of the night,” Light says with a shrug.

While extra staff was needed, some who arrived had to be told to go back home. “In an event like this,” Light explains, “you can have a hangover effect, where the next day you don’t have adequate staff. Then you’re running a different kind of emergency.”

For the anxious family members and friends, a care center was established where they could congregate and receive news.

Next came “the Philadelphia police, the Department of Homeland Security, the FBI, who showed up with guns, badges, everything,” Light says. They wanted to talk to the victims to determine if the crash was terrorism-related. “We had to come up with a way of keeping them out of the medical care area but assure them they were going to be able to get to all the patients.”

And then there were the 64 patients themselves—the reason these many, many members of the Temple community responded so admirably. Robert McNamara, department chair of emergency medicine, wasn’t called in that night, but he participated in the weekly debriefings afterward. “When we reviewed how things happened, one of the recurring themes was that the patients themselves were great,” McNamara says. “They were self-sacrificing. Human beings respond to tragedy in ways that surprise you. Most of the people in the world are

good.” He pauses, then adds, “You don’t always see that when you’re working in an emergency department.”

In the face of a tragic event like the Amtrak derailment, all anyone can do is try valiantly to help. Tomaselli, the med student, was awed by experiencing the events of May 12: “I truly

feel I saw Temple at its best.”

To explore national media coverage of Temple’s handling of the Amtrak disaster, visit news.temple.edu/amtrak.