Research uses texting to continue pre-K lessons at home

Researchers in Temple’s College of Education are exploring the use of text messages as a way to connect parents to their children’s classrooms, bringing kids’ lessons home.

Researchers in Temple’s College of Education are studying the use of texting to connect parents with their children’s classrooms, creating the opportunity for a lesson virtually anywhere, from the bus stop to the grocery store line.

The Text-to-Talk Project, funded by a three-year, $500,000 William Penn Foundation grant awarded to the College of Education’s early childhood education program in May 2015, is exploring text messages as a way for pre-K teachers to keep parents and guardians in the loop about what their children are learning—and give them opportunities to reinforce lessons at home.

“The goal is to try to encourage language development skills with parents, and develop vocabulary used in the classroom to coordinate with vocabulary used at home, to create a home-school connection,” said Barbara Wasik, a professor of educational psychology and PNC Chair in early childhood education who is working on the project. “We’re using texts to do that, so the vocabulary children are learning in the classroom is being texted to the families with suggestions of ways to use that with their children at home.”

Wasik said the project came about in an unconventional way: from the schools to the researchers. She said teachers in Philadelphia schools wanted to find a better way to use technology to connect with students’ parents and guardians, so, in an effort to support that need, the William Penn Foundation stepped in to get Temple researchers involved.

“We designed the project, but it was done collaboratively with the schools,” Wasik said.

Text messages as a connection to the classroom can fill an important gap, particularly for families who don’t have internet access at home, Wasik and Annemarie Hindman, an associate professor of educational psychology also working on the project, pointed out.

“There’s some really solid evidence from the Pew Research Foundation that most low-income families, pretty much everyone, have smartphones, and those smartphones are with them a lot,” Hindman said. “So this means this is a readily available form of communication families are checking regularly. You don’t have to turn on the computer, fire up a web browser. It’s simple.”

The pilot Text-to-Talk program started with 10 teachers in different Philadelphia schools, some of which are located in North Philadelphia and serve dual-language populations, Hindman and Wasik said. They said the reception so far among parents and teachers has been overwhelmingly positive.

“When one of our teachers tried it out in the first year of the project, families were really excited about it,” Hindman said. “Just providing a little window into what is happening in the classroom, with a clear set of guidelines for what a parent can do to enhance that is pretty hard to argue with as a parent.”

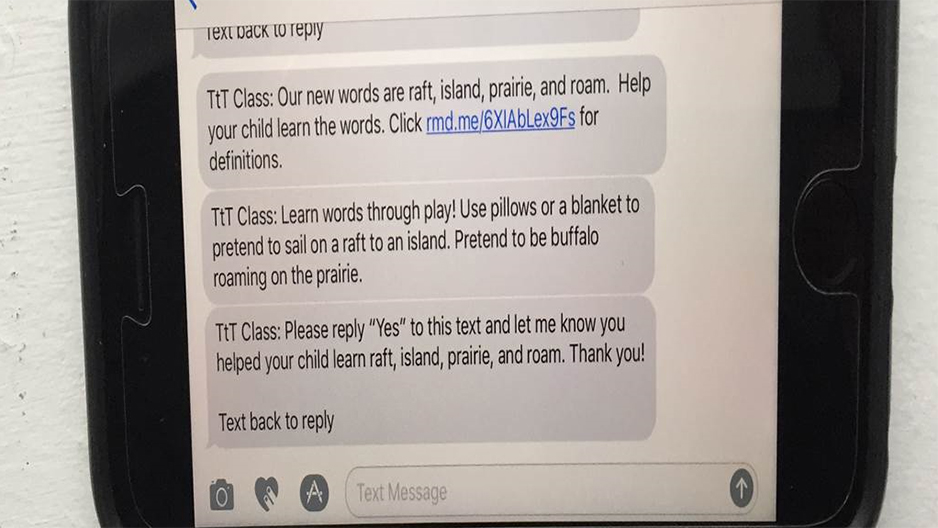

Teachers use an app to set up the text messages to send out to any parents, guardians or other family members of students who opt-in, Wasik and Hindman said. The app provides more anonymity and an easier platform for them to contact a number of families at once.

Beyond parents’ positive reactions, Text-to-Talk’s results have been evident in the classroom, as well.

“The teachers have given us feedback that children seem to be more engaged in class,” said Emily Snell, a College of Education research scientist who’s been playing a more hands-on role in the project in the schools. Snell said teachers generally send out the texts with vocabulary words early in the week for parents and guardians to practice with students at home.

“During the course of the week, the teachers will talk about these words in class, and they reported that the kids come in with a better understanding of what the words are,” Snell said. “Parents are doing activities with the kids at home, so the kids have knowledge of the words they wouldn’t otherwise have had. It makes the classroom instruction more engaging.”

Text messages are increasingly becoming a preferred method of communication between teachers and students’ families, Snell said, and other initiatives around the country—including studies at other universities—have also been exploring the best way to employ texting.

“We’re part of a larger movement that is trying to use technology to design nimble interventions that are low-cost but potentially high-impact,” Snell said. “Texting is a good bang for your buck in terms of providing information.”

As their research on Text-to-Talk continues, Snell, Wasik and Hindman will be working to determine the best content and length for the text messages, along with other best practices for the use of texts for home-school connection, to create a template that other schools will eventually be able to use.

“People use their phones for a lot of things, and the goal for us is to make sure to use the phone, but in a way that it has specific, meaningful outcomes for the kids,” Wasik said. “That would be the goal, and to be able to have it used in more classrooms in both Philadelphia and other places.”