On WRTI, Bob Perkins gives self-isolated listeners a safe haven

The jazz host’s show offers a break from the stresses of COVID-19.

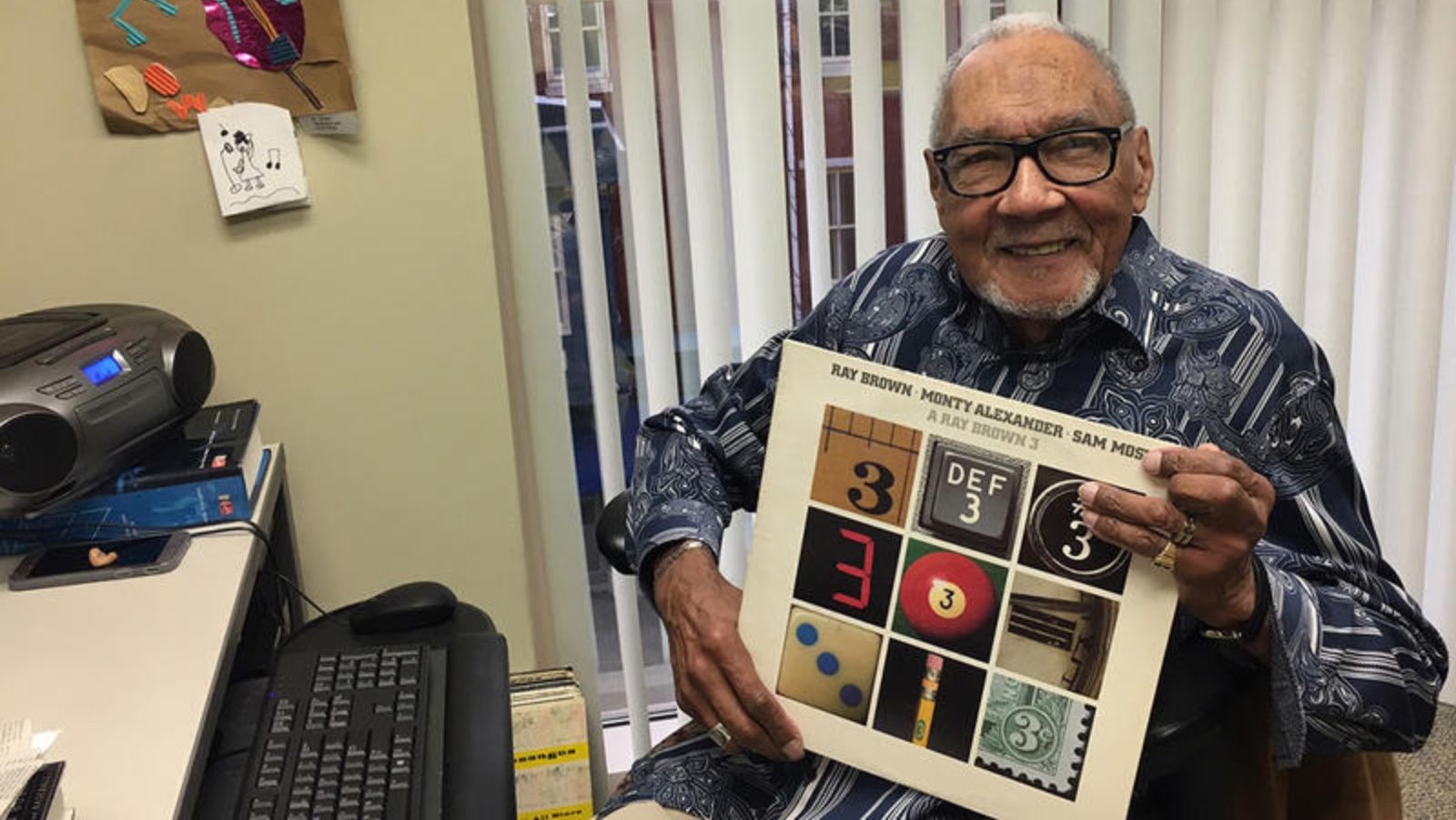

Bob Perkins has been a fixture on Philadelphia’s airwaves for 50 years. Five days a week, on WRTI, “BP with the GM” (that’s Bob Perkins with the Good Music), plays jazz with a connoisseur’s ear and an infectious sense of joy.

His show is an oasis, a source of comfort as listeners cope with the challenges of life during a pandemic.

We spoke with him about his show, the power of radio and the beauty of jazz. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Temple Now: How do you choose the music that you play?

Bob Perkins: I do it—and I’m not trying to be funny—but I do it really by braille, a feel. I’ve been in radio for about 55 years and in Philadelphia for 50 years. And I’ve been a newsman, editorial writer, disc jockey—I guess just about everything with the spoken word in radio. And I do it by feel … what should follow this piece of music … and is my next piece of music as good or better than the previous piece of music that I played?

You don’t know who’s listening, how many people: could be one, could be 10,000. You can never know. But you try to always put that best music forward. It takes a little bit of thought. How is someone out there feeling? Which is a hard thing to do. Am I going to capture their imagination today?

TN: Have you made any changes to your playlist, in light of what’s happening?

BP: No, I just put out the music. I try not to ad-lib and talk about what is going on. People know what is going on. I try to ameliorate that and take the rough edges off if I can, with the music. And hopefully it’s working.

TN: Why was it important for you to keep doing your show?

BP: Well, I still like it. I’ve been in radio for quite some time. This job and that job until I really found my niche in radio and I just happened to walk into a radio station one day and they happened to need someone.

But I had some qualifications, too, because my dad got into radio back in the 1920s, when radio was in its infancy. He was too ill to work; he had rheumatoid arthritis. But he played the radio, that was his only salvation from the pain. And I would sit with him and we would listen. He made his own antennas and we could sit and listen to Chicago, Detroit. I was weaned on radio.

TN: It sounds like being a DJ is something you were always meant to do.

BP: It seems that way. I enjoy it. I think it’s magic, the music I play. I don’t know how they do it. Someone can think of something and express it in a musical form and without hitting any sour notes and make it sound melodic, where you can tap your foot or you can close your eyes and dream on it. They can take you away. That’s the magic part about this thing called music. Especially jazz music. It comes out of the head, out of the heart and out of your soul.

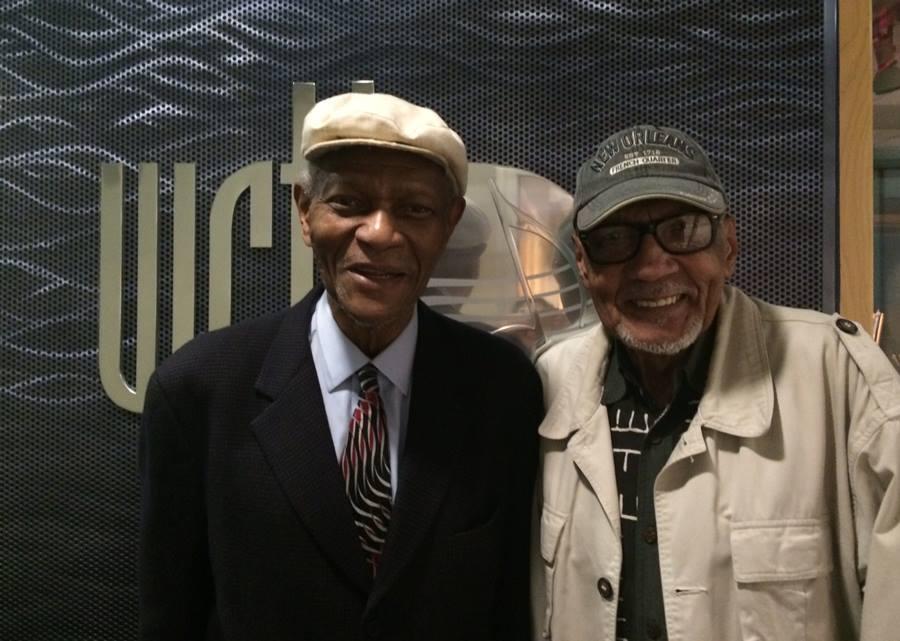

BP with jazz pianist McCoy Tyner at WRTI in 2015. (Photo by WRTI)

TN: What’s the response been to your show recently?

BP: People, they never call me, seemingly. They just let me have my own way and they seem to like what I play. I was out for about four months. I had a mild stroke. I’m just about 90% recovered and the letters that they sent, it was embarrassing to me because of the flattery that they gave me. “We can’t eat our dinner without you. It’s not the same.” You know, it’s magic that I’ve been around that long and people have that much confidence in me. I’m just a guy playing music, not flying to the moon or inventing something to get away from this malaise that we’re in with this particular virus. Not doing anything heroic. I’m just playing music. And to have that kind of confidence in a guy who’s just sitting around playing music [laughs], that’s pretty good.

TN: Why do you feel people respond so strongly to music? How does it connect with them in a way other things don’t?

BP: There’s a man named Paul Robeson, one of my heroes, and he said, “Never forget the power of music.” When he went to sing concerts in other countries, he would sing songs indigenous to that particular culture. I don’t know why music is so much more powerful than some other entity. But there’s something about music. It’s a rallying cry. Or when times are not tight and everything’s loose? Let’s have fun; let’s have a beer. Let’s sit around and gab, whatever the case may be.

TN: People staying at home have been listening more to the radio and less to streaming services. Why might that be?

BP: I don’t know. When I was a kid, which was a long time ago, radio was called “the theater of the mind.” There was a person named The Shadow. And you had to visualize this man who could make himself invisible. You had to sit around the radio and visualize.

Maybe we’re getting back to that today. If there’s any good thing about this—and there’s very little good about it—it’s the fact that maybe families are getting together again and eating at the dinner table again, in the kitchen or living room, and doing things together again.

TN: When you had your stroke, did the way people reacted to you being off the air take you by surprise?

BP: Yes, it really did. I knew that people kind of liked my music. But I didn’t really visualize the response that I got. I was out for almost four months. That’s a long time. And people do forget. But it seems like the longer I stayed out, [chuckles] the more positive response I got. So when I came back I got these emails saying, “Oh, we’re glad you’re back.” I save all my emails. Those letters always remind me that you have people out there listening to you and they’re expecting some good things from you.

—Edirin Oputu