Racial injustice has been fuelled by centuries of prejudiced hierarchies

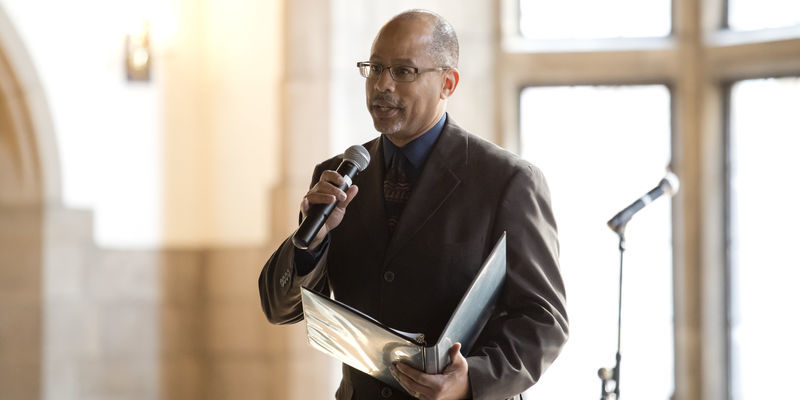

Professor of Africology and African American Studies Molefi Kete Asante discusses the George Floyd protests and the concept of Afrocentricity.

The author of more than 90 books and 500 articles, Molefi Kete Asante is one of the world’s most prolific African American scholars. Professor and chair of the College of Liberal Arts’ Department of Africology and African American Studies—one of the oldest in the U.S. and the first to offer a doctoral program—Asante is the founding and current editor of the Journal of Black Studies, the top peer-reviewed journal in the field.

“The young people are writing a new history of America. They believe that it’s possible to have a narrative of American society that is not based on negativity,” Asante said. “That even if there were things that happened in the past that were negative, the future doesn’t have to be that way. And this futurism is I think something that’s going to generate change.”

We spoke with Asante about the George Floyd protests, Afrocentricity and how people can bring about lasting change.

Temple Now: You’re a pioneer of Afrocentricity. What is that and how does it relate to the protests against racial and social injustice that are happening now?

Molefi Kete Asante: I think that this movement is fundamentally an Afrocentric-inspired movement. Afrocentricity is the idea that people of African descent are subjects of the human narrative and not marginal to the European experience. That in order to understand world history and African history or African experiences, whether they are transgenerational, meaning from different centuries, or whether they are transcultural, meaning whether they are on the continent of Africa or in South America and North America or Europe, or in Asia. That African people must be viewed and must learn to view ourselves in the middle of our own story. Otherwise we participate in the racist discourse of Europe. So basically what I have seen in this current movement is that there is now a critical mass of Black people, white people, Asian people and Latinx people who understand this fundamental idea.

TN: In your book, Erasing Racism, you wrote, “Racism often becomes somebody else’s problem, when it is really a national concern.” What did you mean by that?

MKA: Racism is not anything more than a problem that engulfs the entire nation. Race is a constructed phenomenon. There [is] no scientific basis to the notion of race. There’s one race, the human race. But what has happened is that in the way the Eurocentric world views things, you have the ranking of human beings on the basis of skin color, texture, religion, gender, previous conditions of servitude, etc. This ranking, this hierarchy perhaps is the very generator of what we call racism. That is the fundamental problem of Europe: The notion that was established in the European mind by many of the best European writers—I mean beginning in the 15th [or] 14th century—that the Nordics or the Aryans were at the top and the Africans and the Native Americans were at the bottom, and everybody else was in between. This hierarchy had emerged. Our former PhD student who is very brilliant and has written How to be an Antiracist, Ibram Kendi, CLA ’07, has argued that racist policy is what has really crippled the African American community, that you have to deal with the question of policies, what people enact.

But my argument is a little before that, and it is that racism is generated by the notion of ranking people on the basis of skin color and hair texture and so forth. The hierarchy is the problem. Because if we solved the problems of police brutality tomorrow, and we defunded all the police programs and reconstruct them, we will still have other areas such as education, such as housing, such as banking, such as university programs—all these things will still be there and be arenas of racism. Because the generator is still the same. The assumption is that African people are less than. And if you make that assumption, then you feel that African people do not deserve equal treatment in any way. And I think that’s what the society has done for so many years.

Molefi Kete Asante feels young people are writing a new history of the United States. (Photo by Joseph V. Labolito)

TN: There have been protests against racial and social injustice and police brutality before. What makes the ones inspired by George Floyd’s death different?

MKA: The most prominent thing that comes to my mind is that probably for the first time, there is such a broad understanding on the part of the young white people. That racism is endemic to the American way of life. The second part would be the social media because social media itself creates its own energy and dynamics. I remember the Kerner Commission report [which examined the cause of the 1967 race riots in the U.S.]. One of the things that it blamed the uprising and the African American communities for was creating a national consciousness of discrimination. People would look at television and they would see something going on in Birmingham and maybe people in Houston would have their own uprising. The television stations stopped showing incidents in cities where there was an uprising on the national news. And in a sense, basically shut down the distribution of information about what was going on in one city and in one place. So, you didn’t get the idea that it was happening everywhere. But the incredible thing about social media now is that it is not dependent on the networks or the cable news. People were showing me images of things happening after the George Floyd murder that people had taken on their own cell phones. Lots of people were becoming journalists.

TN: How can people who have already been working toward racial equity make the best use of this moment?

MKA: I would love to see some of these young people take on particular issues in the American community, for example, the whole issue of the statues of the Confederacy. It seems to me logical that they should have been pulled down a long time ago. There are many African Americans who have called for this for generations. But the problem now is what is the narrative of American history? I’ve traveled to Germany many times. And in Germany, you do not see any statues to Nazis. They don’t want to honor the Nazi regime. In fact, it’s against the law.

But in America, what happened was that when the Confederacy was defeated in 1865 there was no transformation of the philosophies of the South, or even of the nation to the degree that we were able to change the way people thought about race. When you have a treasonous rebellion against the state, almost no society would honor the traces and put those traces up as statues. But this country did it because again, I go back to hierarchy: As far as the whites who had left the union were concerned, the four and a half million Black people who had been enslaved for 246 years did not count as much as the white people who had rebelled against the government. In fact, there were many people in the North that still thought that white people were a higher race and deserving of more worth.

TN: What advice would you give people who would like to get involved in their communities in some way?

MKA: I think that there are probably a couple of things that people can do. I would like to see students organize chapters of clubs that deal with revisiting the historical experiences of America itself. I don’t know what the name of such clubs would be, but it just seems to me that what is happening in the African American community is that at least a certain part of that community has a much wider appreciation for historical facts about European invasions than the white community. For example, if you talk to a Black person, immediately, Black people take the side of the Native Americans and say their country was stolen from them. But if you talk to white people about this, this becomes an issue of contention only because white people have an assumption that they have a right to take the native peoples’ land. And that assumption is based, again, on the ranking of people. It’s a hierarchy. These people do not farm the land. They are only hunters, so they can not be as highly ranked as people who farm or engage in agriculture. So whites have the right to take the land from them and to do something with it. That is the European mentality. African people understand that. We know that that kind of thing doesn’t take into consideration any of the philosophy or traditions of native peoples and that’s a flaw.

—Edirin Oputu