Curating Philadelphia

Diane Turner, CLA ’83, ’91, ’93, oversees the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple, which includes the history of civil rights in North Philadelphia.

Walking through the glass doors on the first floor of Sullivan Hall into the Blockson is like stepping back into history. It’s a treasure trove of more than 150,000 books and artifacts documenting more than 400 years of the African and the African American experiences. In 1984, Philadelphia-based historian Charles L. Blockson became curator after he donated his private collection of journals, manuscripts, newspapers, pamphlets, photographs, posters, sheet music and rare ephemera to the university. He spent 22 years building on the collection and creating a space that would serve both historians and those simply interested in understanding more about African and African American heritages. To learn more, we sat down with Turner, who took over as curator when Blockson retired in 2006.

You get to spend every day in the one of the nation’s premier centers for research on the African diaspora. What exactly do you do?

Diane Turner (DT): As curator, I am in charge of preserving and building this amazing collection. People contact me frequently with items they want to donate—perhaps something they found tucked away in an attic. A few years ago, we hosted a reunion of the Philadelphia-based survivors of the Tuskegee Airmen, a distinguished World War II fleet of airmen who became the first military aviators of color to join the U.S. Armed Forces. Although they fought alongside a diverse set of soldiers, they faced racism and discrimination when they came home. The stories they shared really gave me a new appreciation for their sacrifice. Instead of letting their experiences get lost or erased, the surviving members decided it would be best to have their stories preserved at the Blockson. They donated hundreds of photographs, correspondence and other documents to the collection. I tell people all the time that I have the best job on campus. I am exposed to something new every day.

Who are the primary users of the collection?

DT: We see a wide range of folks come through our doors. It’s not uncommon for a political science major working on an undergraduate research paper to be seated at one of our tables next to a well-known historian. Recently, Gerald Early—professor in the Humanities and Social Sciences Department at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, and author of a forthcoming book on Odunde, Philadelphia’s largest African American festival—stopped by to conduct research on his aunt Lois Fernandez, the founder of Odunde.

What are some of your favorite items housed here and why?

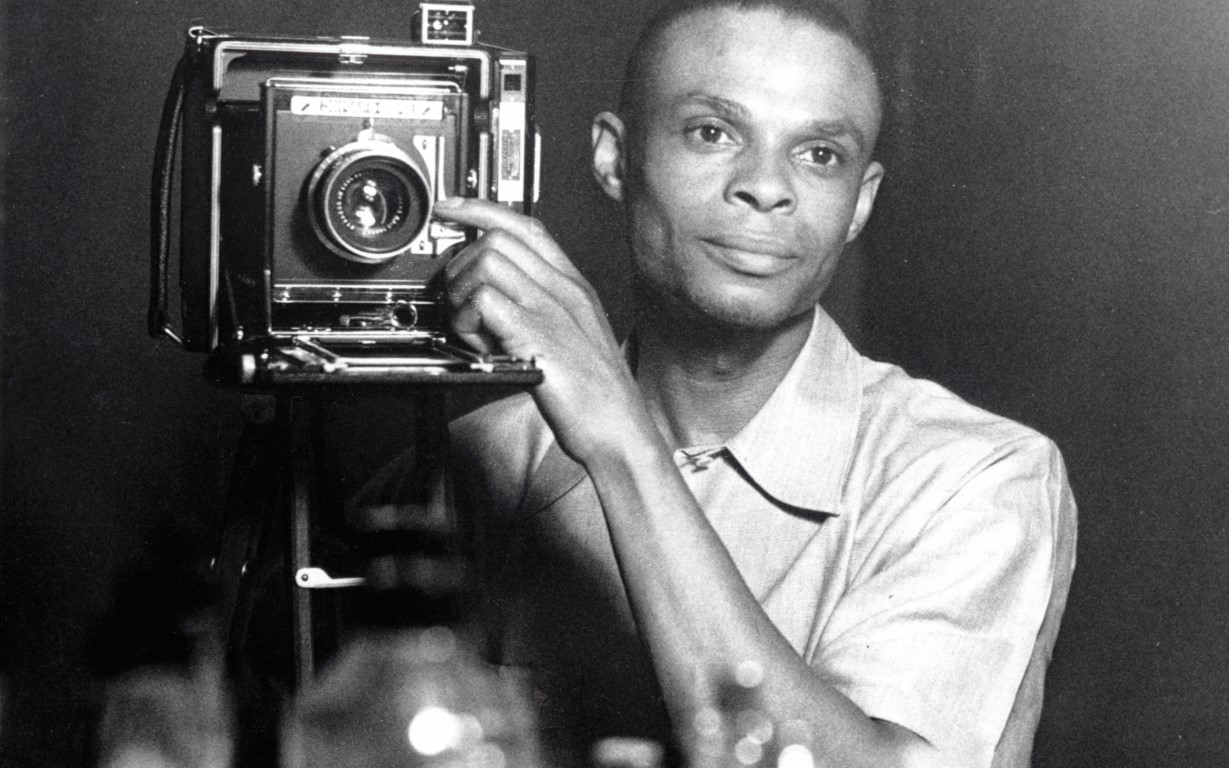

DT: It’s hard to pick just one item. Visitors will often come in and focus on paintings on the wall or artifacts in the display case not realizing that we have original source material for important events in history. Each item is as important as the other because when you look back, there’s really no separation between history and culture. I try to convey that when I teach. For example, when teaching the civil rights movement, I use poetry, film and even art to help students understand the political and social climate. Our collection of photos by Philadelphia born, self-taught photographer John W. Mosley shows examples of how art and history collide. Mosley had an eye for capturing subtle, yet emblematic, moments of black life in and around Philadelphia. One of his most popular images depicts civil rights leader Julian Bond, as a young man, with Paul Robeson.

You are also the author of a children’s book called My Name Is Oney Judge, about a young woman who escaped a life of slavery on George Washington’s plantation. What motivates you in your work?

DT: During my sophomore year at Temple, I spent a semester in Nigeria studying the revolutionary work of Afrobeat legend and human rights activist Fela Kuti. I was inspired by his ability to use music as a weapon against the dictatorial Nigerian government of his day. I’m driven to shed light on stories like his. Although they were centuries apart, Kuti and Judge share the distinction of being unafraid. Like Kuti, Judge stood up against injustice and worked for a better life for herself and her people.

What other projects are you currently involved with on campus?

DT: I’m currently working with Molefi Asante, chair of the Department of African American Studies, to develop two courses that will focus on African American history in Philadelphia. Philadelphia played a huge role in the civil rights movement. The courses will draw from our Civil Rights in a Northern City digital archive. [Also see “Moore Power,” Temple, winter 2013, pages 16–21, and visit northerncity.library.temple.edu.] We partnered with the Special Collection Research Center to preserve the materials in the archive, and I conducted the oral histories housed in it of the Cecil B. Moore Freedom Fighters, who were teenagers during the fight to desegregate nearby Girard College in the ’50s.

Are any of your programs open to the public?

DT: The community should feel like the Blockson Collection is their front door to Temple. Overall, our programs and events are designed with the general public in mind. This summer, we will be honoring poet and activist Professor Emerita Sonia Sanchez during our annual Juneteenth celebration on June 17. I am especially excited about our annual jazz appreciation concert this spring. North Philadelphia was once the center of the jazz world. Consequently, our spring concert always draws a big crowd. When Mr. Blockson brought the collection to Temple in 1984, he chose the university because of its focus on diversity and its location in the heart of an African-American community. So, although the center itself was placed at the center of campus, this 3,000-square-foot collection isn’t just for academics.