Temple researchers delve into childhood memory

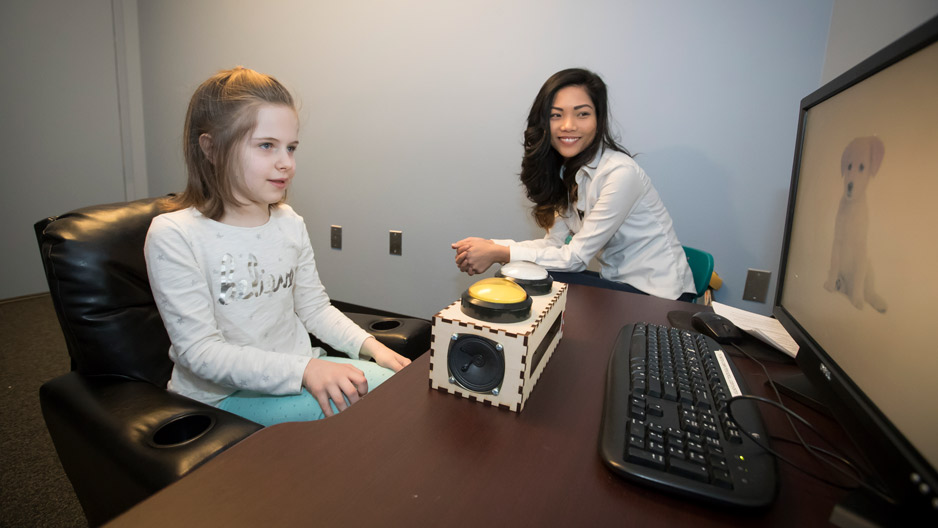

Professor Nora Newcombe and graduate student Zoe Ngo’s study revealed important findings related to development of pattern separation as part of episodic memory in young children.

Have you ever wondered why you have no memories from the earliest years of your childhood, yet you remember skills you learned in those years, like walking and talking?

New research by Temple Laura H. Carnell Professor of Psychology Nora Newcombe and graduate student Zoe Ngo is bringing us a step closer to potentially answering that question. Newcombe and Ngo’s recent project studies pattern separation, a process of episodic memory, in children ages 4 and 6 to determine when it develops and how it relates to other memory processes.

“Children are very interesting to study for episodic memory, because we don’t have any memories in the first two years of life, and all of a sudden, we’re able to form these memories for specific past events,” Ngo said. “So there must be something going on in early childhood or middle childhood that’s very interesting.”

Newcombe and Ngo’s study, which was conducted by administering computer-based tests designed to work like games to 32 4-year-olds, 32 6-year-olds, and 50 young adults as a control group, first measured aptitude for relational memory, the memory process that helps differentiate between, for example, a trip with your dog to the park when you ran into your friend and a different trip to the park, Newcombe explains.

“In order to remember those kinds of autobiographical events, you need to relate one element to another,” said Newcombe, who has studied various aspects of memory throughout her career. “You have have gone on many walks in the park, some of which may not have involved Fido [your dog], many in which you have not met your friend.”

Photography by: Betsy Manning

Research by psychology Professor Nora Newcombe and graduate student Zoe Ngo (pictured) measures pattern separation, a memory process, in young children.

Pattern separation—a process examined in children for the first time in Newcombe and Ngo’s study—on the other hand, is a component of episodic memory that allows people to distinguish memory episodes that are very similar, such as where you parked your car today versus where you parked yesterday. The second part of the study measured pattern separation by showing children and young adults a series of photos, and then asking them later to compare the first set of pictures with a new set of pictures, some of which were exactly the same, others of which were similar or completely different.

The results? Both relational memory and pattern separation tend to be far more developed in 6-year-olds than in 4-year-olds, Newcombe and Ngo said. Interestingly, the 6-year-olds performed about as well as young adults on the test, the researchers said, and development of pattern separation and relational memory in children showed no correlation to each other—meaning that they likely develop at different paces.

“So a 4-year-old could be very good at relational memory, but not good at pattern separation, or vice versa,” Newcombe explained.

The research has several implications for everyday life, from courtrooms to interventions for children with compromised episodic memory as a result of conditions such as type 1 diabetes.

Both Newcombe and Ngo said they chose this area to study because they are fascinated by memory development, a process that still poses more questions than answers.

“It’s an old chestnut in psychology called infantile amnesia, or childhood amnesia—adults don’t remember when they were a baby or when they were a toddler,” Newcombe said. “It’s interesting, because why don’t we remember those first few years of life? We know that we were awake and we could talk and we were being molded by our environment. So why is it that we can’t remember it?”