Envisioning resilient cities

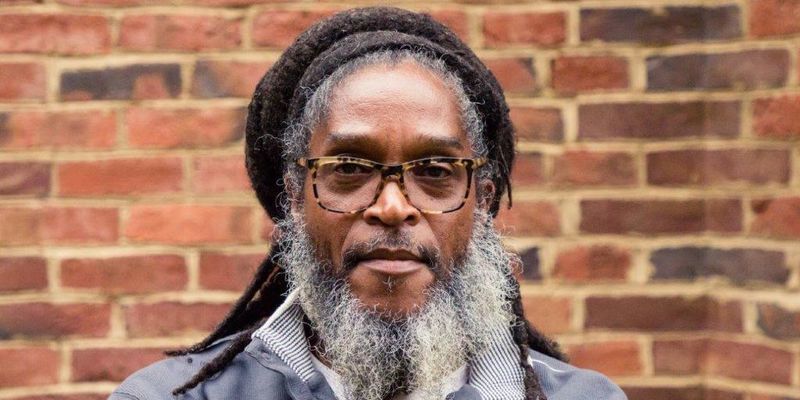

Tyler Assistant Professor of Architecture and 2020–2021 Fulbright scholar Gabriel Kaprielian uses board games, interactive digital media, and virtual reality to investigate sea level rise and speculate about the future of our urban waterfronts.

Gabriel Kaprielian is not a conventional professor of architecture. But maybe tradition is not what we need when envisioning a more sustainable world, city or waterfront.

In addition to teaching, Kaprielian is an artist, designer and urban planner whose work explores climate change adaptation, particularly sea level rise.

The assistant professor of architecture and Fulbright scholar creates digital platforms to imagine how cities can respond to climate change. Speculative in nature, his varied projects all strive to communicate creatively, inspire collective optimism and build community resilience.

We spoke with him about his philosophy and his work, his Fulbright award and upcoming research in Singapore.

Temple Now: How did you get interested in studying sea level rise?

Gabriel Kaprielian: I grew up in northern California on the waterfront and have lived near the coast most of my life. I was based in the Bay Area while working on my thesis and in some ways, I chose UC Berkeley for graduate school because I was interested in this issue.

There are three main approaches to tackling the issues of sea level rise: retreat, protect or accommodate. One plan is to build up walls to protect the communities against sea level rise. However, in the case of the Bay Area, this would result in submerging all of the tidal wetlands and destroying one of the most important ecosystems in North America. This approach pits the built and natural environment against each other in what I believe is a false dichotomy.

My graduate research was based on the premise that cities and ecosystems are intricately connected and therefore a plan for sea level rise protection must accommodate both the tidal wetlands, new development and the people that live there.

TN: How do you approach your work?

GK: Part of the reason I was interested in joining Temple and the Tyler School of Art and Architecture was the focus on creative ways of exploring research and practice.

I’m always looking for avenues to talk about complex issues like climate change, and reframe the problems as potential opportunities for design innovation that can lead to important discussions among diverse stakeholders.

Instead of trying to come up with a solution myself, which is the knee-jerk reaction for architects and planners, my work tries to develop platforms for creative communication about these issues so we can bring more people to the table.

TN: Can you talk about the board game you created, Sea-Level Hi-Rise!?

GK: The original idea for the sea level rise board game came while doing my thesis. Part of the idea was trying to think of ways to engage the public and have it be interactive. The project never materialized but later on, I developed the game as a teaching tool.

The game is both competitive and collaborative, where each stakeholder or player has their own individual goals and also the shared goal of protecting all development from sea level rise. Strategies of adaptation, accommodation or retreat are combined with tactics like levees, walls and wetlands.

Students both design and play the game, combining their site analysis and resilience strategies to have discussions about different potential scenarios. By playing through each of the game’s characters (developer, environmentalist, mayor, resident), they develop design empathy and begin to understand the different needs of all the stakeholders.

Through the act of playing they are having really important conversations that lead to new understandings and ways to approach these complex issues. It takes some of the pressure away and allows people to empathize with each other more.

TN: You also designed a website to contextualize waterfront development and inform resilient strategies. Why did you take this uncommon approach?

GK: The adapting waterfronts website is an interactive digital platform that builds knowledge about the past, present and future of waterfront transformations. It reveals hidden history and sea level rise threats, while illustrating different ways one can layer resilience strategies. A website is really not a traditional thing that somebody in architecture would be trying to develop. But I think online interfaces can reach more people and convey information better.

Thinking outside of the traditional box is important, especially as we try to tackle these really complex issues; the wicked problems of the 21st century and beyond. We are going to need to develop new platforms and toolkits.

TN: You were chosen to serve as lead artist for the American Arts Incubator in Lima, Peru, a digital and new media art program by the U.S. Department of State to foster discourse and grow communities. Can you talk about your experience?

GK: Yes, this was an international collaboration between partners in the U.S. and Peru including ZERO1, the U.S. Embassy, the University of Engineering and Technology, and the Contemporary Art Museum in Lima. Through my role as lead artist, I had the opportunity to work with 23 local artists, activists and architects and help amplify their voices through a shared project called “Lima 2100: Collective Resilience through Adaptive Urbanism.”

I was interested in exploring the topic of urban development through the lens of urban health, social equity and climate change, while imagining what Lima would be like in the year 2100. Originally I was planning to go in person and spend a month developing this program, but that didn’t happen because of the pandemic so we did it virtually.

I had been experimenting with virtual reality and augmented reality over many years, but during the pandemic it was something that I actively started working on more. Because we were not able to have an in-person exhibition at the museum, I created a digital model of the gallery for a virtual reality public exhibition. I placed everyone’s art there and for the first time during the project, we were able to gather together in one room with our virtual avatars.

The virtual gallery is now a permanent part of the museum and offers opportunities for digital artists to show their work and has the potential to reach more people who wouldn’t necessarily go to the museum. It also gave artists new opportunities to present their work, especially if they don’t have the funds to create expensive work to be physically built and installed in the museum. I was proud of how we were able to adapt to the changing circumstances due to the pandemic and in many ways create a more sustainable platform for future exhibition.

TN: Collective resilience is an idea that is important to your work. Can you explain more about what it is?

GK: Collective resilience refers to the fact that we are all interconnected. The resilience of one community affects everybody and so we have to be thinking about our collective resilience and our collective voice.

Studies have shown that wealthier communities get more resources after major storm events or sea level rise. We have to work to ensure we’re not just protecting certain communities.

We have to be educated and aware and think about how we’re engaging with these projects and how one project affects the larger community, whether it be a neighborhood, the city or the region.

The experience I get in Singapore is going to be really useful to frame some of these problems and solutions so that we can have collective resilience, not just one group, in one place thinking about it, but now starting to build this network of people who are thinking about it.

TN: Can you tell us more about what you’ll be doing in Singapore as part of your Fulbright award?

GK: My Fulbright is going to be working within an interdisciplinary collaboration of climate change scientists at the Earth Observatory of Singapore. We will be projecting some of the research they’re doing onto different possible scenarios in order to frame the waterfront in the context of past, present and future. Borrowing the idea from Postcards From the Future to imagine Singapore in the year 2100.

Singapore has really great examples of what you call sustainable urbanism, whether it be green architecture or great transportation systems, the list goes on and on. But they are very susceptible to sea level rise since 25% of their built environment is constructed on reclaimed land.

Cities around the world are built on tidal waterfronts, which goes back to a history of global maritime trade. In many ways, cities haven’t figured out what to do with these urban waterfronts or how to make them more resilient and better places for people and the ecosystem.

I see this as an opportunity to collectively redefine our urban waterfronts to be places that are resilient to sea level rise and increased storm events, while providing a better environment for people and the more-than-human world. This will be an ongoing project that considers different scenarios as we design for the future, not just the next five and 10 years down the road, but even the next 50 or 100 years.