Understanding American Gun Violence Part 2: How to solve the American gun epidemic

Experts from Temple University are tackling the issue of gun violence from a variety of angles. They explain what can be done to permanently address America’s gun violence epidemic.

Laurence Steinberg squints up at the glossy, backlit rows of the latest MRI scans from his research study. He leans in close as his fingers trace over small details in the images. It’s these details at the tips of his fingers that give him a clear and compelling answer about why young people are so much more likely to engage in gun violence.

One thing has become clear to Steinberg: The increasing rates of gun violence also provide a growing amount of evidence that there are ways to permanently address gun violence.

We live in a country that has accepted the possibility of being shot as an unfortunate but unavoidable cost of living in America. But Understanding American gun violence part 1: The evolution of America’s relationship with firearms, the first article in this series, breaks down all the ways in which this is not true.

A unique set of circumstances has led to America’s gun problem. And while it is complex and rooted in historical and sociological factors, Temple experts studying gun violence and reform remain confident that solutions exist that could significantly reduce the American gun epidemic.

The scope of their solutions range from highly targeted intervention strategies to broader measures like gun reform and greater investment in education. And while they all agree that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to gun violence in America, there is evidence that the ideas and initiatives listed below would be successful in making progress towards eradicating the American gun violence epidemic.

Key takeaways

- Mark Rahdert, professor of constitutional law: State and federal lawmakers should enact gun reform measures that challenge the Supreme Court’s 2008 Heller decision and its interpretation of the Second Amendment, which gave Americans the constitutional right to own and carry firearms. In addition, lawmakers should consider expanding the Supreme Court slowly over time.

- Timothy Welbeck, assistant professor of Africology and African American studies and director of Temple University’s Center for Anti-Racism: There should be a conversation about reintroducing an assault weapons ban because the now-expired 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban led to a decrease in assault weapons-related deaths.

- Laurence Steinberg, professor of psychology and neuroscience: The sale of long guns to Americans under the age of 21 should be banned due to the gap that exists between impulses and impulse control in adolescent brain development.

- Jennifer Pollitt, assistant director of the Gender, Sexuality and Womens Studies Department: An investment in trauma-informed, healing-centered education will help address the underlying factors that lead young men to engage in gun violence, and redefining masculinity will help men express negative emotions in healthier ways that don’t involve violence.

- Jessica Beard, trauma surgeon, public health researcher at Temple University Hospital and director of research for the Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting: A public health approach that identifies and provides supportive intervention for individuals most likely to engage in gun violence, like the Cure Violence model, has been shown to reduce community gun violence. In addition, investments in place-based interventions have been shown to decrease gun violence. And, as a trauma surgeon, Beard believes more medical professionals should be trained to provide trauma-informed healthcare so that gun violence victims can have the best care possible.

- Scott Charles, trauma outreach coordinator at Temple University Hospital: finds that a sense of hopelessness can be pervasive in high-poverty disinvested communities and that this hopelessness and violence often go hand-in-hand.

- David Boardman, dean of the Klein College of Media and Communication and former editor-in-chief of The Seattle Times, and Amy Goldberg, dean of the Lewis Katz School of Medicine: The media needs to include more graphic images of mass shooting victims in their reporting to help Americans better understand the damage that assault-style weapons have on human bodies.

Clarify the limits of the Second Amendment

The Supreme Court’s 2008 Heller decision gave American citizens the constitutional right to own and carry firearms. This means that only the Supreme Court has the power to change this interpretation of the Second Amendment. But Mark Rahdert, professor of constitutional law, clarifies that the court is unlikely to do this any time soon because justices have lifetime appointments and the court currently has a majority of conservative judges who favor an expansive interpretation of the Second Amendment.

When a current justice either dies in office or retires, the president has the power to appoint a new justice to the court, provided that his appointment is confirmed by a majority of the Senate. The Republican Senate’s refusal to consider President Obama’s nominee after Justice Scalia died, combined with President Trump’s ability to name three new justices to the court, has effectively guaranteed a pro-gun rights majority on the court for the foreseeable future.

This leaves the work down to the lawmakers. Technically, Congress has the option to begin the process of amending the Constitution in a way that reflects the modern reality of our society. But an amendment requires supermajority support in both houses of Congress, plus ratification of the amendment by legislative majorities in three-fourths of the states. However, due to the rancorous political divisions amongst American lawmakers, Rahdert says this option is also “virtually impossible.”

The most realistic avenue is for state and federal lawmakers to enact regulations—even modest ones—that would test the Supreme Court’s current interpretation of the Second Amendment. This path would take time. It would require laws to be passed with the understanding that they would likely be contested and that many would ultimately fail.

But litigation would send these laws to the courts for review, and in some instances, they would make it to the Supreme Court. The result would be to put pressure on the court to rethink its position on the scope of Second Amendment rights. Over time—calculated in decades, not just years—this could eventually bring about a more flexible approach to the constitutionality of gun regulation.

The court’s current interpretation has left the door slightly ajar for gun regulations to be put in place. “The court has acknowledged that the rights under the Second Amendment are not absolute and are subject to some limitation. But they’ve been very vague about what those limitations are,” says Rahdert. So contested legislation that makes its way to the Supreme Court would force the court to start clarifying the limits of the Second Amendment, which, in turn, would likely put some gun reform measures in place.

Expand the Supreme Court

The idea of expanding the court is a delicate one but could speed up the timeline of Rahdert’s proposed process for forcing the court to clarify the limits of the Second Amendment.

In the days leading up to Biden taking office, a handful of Democratic lawmakers vocally supported the idea of immediately adding four seats to the Supreme Court to rebalance the number of liberal and conservative justices. But this approach was unrealistic given the close division in the Senate.

Expanding the size of the court requires legislation from Congress, and Democrats do not have the votes to make this happen. In addition, adding four seats would only inspire retaliation from Republicans as soon as they had the opportunity. Rahdert says this kind of political warfare over the Supreme Court would be potentially very damaging and destabilizing.

However, there is a more diplomatic and effective way to expand the Supreme Court, according to Rahdert. He proposes two new justices be added to the Supreme Court per presidential term until the court reaches a total of 15 justices. This approach would be more likely to receive bipartisan support because it wouldn’t give either party an obvious advantage.

More justices would mean that the court could accomplish much more, especially if they were required to do some of their work in smaller panels rather than as a whole court. Rahdert believes an expanded court would also reduce the potential power of single justices and over time increase the regularity of court turnover. Ultimately, it would be less likely that there would be a pro-gun rights majority—or any other kind of majority—with a court that was expanded slowly over time.

Increase federal funding of gun violence research

To trauma surgeon Jessica Beard, there is one particularly obvious step that lawmakers can take to address the gun violence epidemic: allocate significantly more federal funding towards gun violence research.

“Being able to deeply understand all the many complicated facets of what is causing firearm injury and how we can effectively prevent it is going to take true investment of dollars, people, expertise and time,” she says.

Right now the amount of funding that is being allocated to this kind of research doesn’t match the gravity of the issue. Beard feels that the federal government has the opportunity—and the responsibility—to show leadership in supporting research that frames gun violence as a public health crisis. And, at the moment, she believes U.S. lawmakers are increasingly but not yet adequately stepping up to the challenge.

Meaningful gun reform

The 1994 Federal Assault Weapons Ban is an example of gun reform that produced positive results. The ban resulted in a decline in assault weapon-related deaths, according to Assistant Professor of Africology and African American Studies Timothy Welbeck.

Following its expiration in 2004, deaths attributed to assault weapons increased again. “We can have a debate about the types of restrictions that should be in place, but we should move beyond the point where we think that there should be no conversation about gun reform,” Welbeck says.

Professor of Psychology and Neuroscience Laurence Steinberg supports legislation that would ban the sale of long guns, such as assault weapons, to people under the age of 21. His research on impulse control in young adults informs his stance, and he believes this measure, which would limit access to deadly weapons among a population that is not fully cognitively developed, would reduce gun violence.

“We use 21 to regulate lots of behaviors that people engage in,” he said. “We don’t allow people to purchase alcohol when they’re younger than 21 because we believe that they can’t handle it very well. And that should apply to firearms as well.”

Invest in public education

Scott Charles, trauma outreach coordinator at Temple University Hospital, finds that a feeling of hopelessness exists within communities that have limited public funding for their schools. He believes that this hopelessness and violence go hand in hand.

“Young Black men, who are disproportionately impacted by gun violence, are residing in neighborhoods with the highest levels of structural disadvantage,” Charles says. “To address the sense of desperation that can lead to violence, it is imperative that we make economic investments that improve their educational and employment opportunities.”

And beyond mere investment in public education, Assistant Director of the Gender, Sexuality and Women’s Studies Department Jennifer Pollitt believes that trauma-informed, healing-centered education is crucial to steering vulnerable young boys away from gun violence.

She pointed out that young boys are kicked out of school for misbehaving at much higher rates than young women. “In reality they’re emotionally struggling, but they’ve just been socialized to cope by acting out,” Pollitt says. Trauma-informed, healing-centered education places a greater emphasis on treating the root cause of “bad behavior” so that these young boys can stay in school and thrive.

Trauma-informed healthcare to support gun violence victims

After spending 14 years as a healthcare provider, it has become clear to Beard that healthcare providers need to be trained to understand trauma to provide the best care to their patients. “As healthcare providers, we need to be mindful of trauma. For example, undressing patients or causing them pain during an emergency procedure can cause trauma,” she says.

Becoming a trauma-informed healthcare provider also means acknowledging that a patient who has experienced trauma is going to behave in trauma-related ways. In a healthcare setting, this is vital to proper care. Providers need to be trained to identify these behaviors quickly and incorporate that into their care plan.

There are various ways the medical community can integrate trauma-informed care into their practices. Beard cites Temple University Hospital as an example of one way to do this. The hospital is currently participating in a pilot training program run by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma that is training providers on trauma-informed care.

Place-based interventions as gun violence prevention

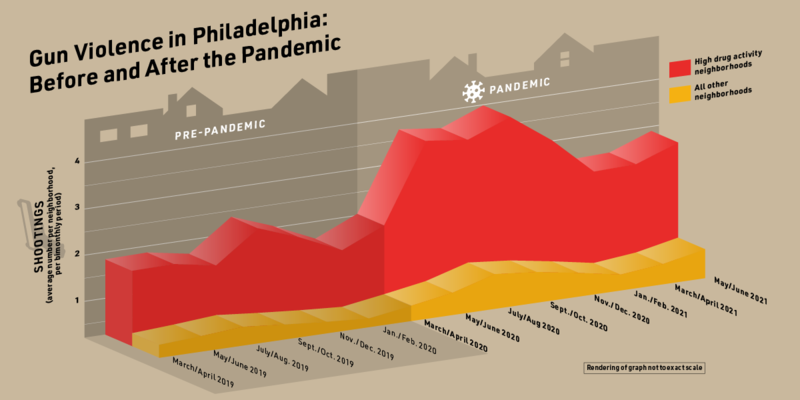

Beard also advocates for place-based interventions that include investing in the development of green spaces, tree cover and parks and improving building edifices and vacant lots. While it might be confusing at first to hear a trauma surgeon championing neighborhood beautification projects, she explains that the risk of getting shot is a place-based risk. Philadelphia neighborhoods that were redlined in the past are now the places where people have the highest risk of being shot.

Beard references the research of Eugenia South, Beard’s peer and fellow medical professional, as clear evidence that place-based interventions are a necessary component to addressing American gun violence. South’s research focused on providing interventions to vacant lots and abandoned homes in marginalized communities across Philadelphia and studying the results of these changes. In the communities where South’s team planted gardens, cleaned up trash and improved the facade of vacant buildings, her team observed a dramatic decline in gun violence.

Violence interruption to prevent gun violence

The Center for Urban Bioethics at Temple’s Lewis Katz School of Medicine has adopted the Cure Violence approach to reducing gun violence through a series of programs that date back to 2011. The approach is named for a Chicago-based initiative, which saw a 67% reduction in shootings the first year it was introduced in West Garfield Park, a neighborhood with high rates of gun violence.

The Center for Urban Bioethics' programs rely on outreach workers to identify individuals who are most likely to engage in gun violence. They then target these individuals with programs designed to help them change their attitudes and behaviors. These efforts may include obtaining a driver’s license, helping them attend school, connecting them with a mentor in their desired job field or giving them job-specific training.

By establishing relationships with individuals at risk of engaging in gun violence, outreach workers also play a role in helping individuals settle interpersonal disputes before they turn violent.

Roman’s 2017 evaluation of the Center for Urban Bioethics' programs modeled after Cure Violence found that they reduced shootings by 30% in three Philadelphia neighborhoods. The model has since been replicated in more than 200 cities around the world.

Another similar program run by Temple University Hospital is called Temple Safety Net. The program includes a series of initiatives that educate youth about the medical realities of gun violence, provide free gun locks to Philadelphians with firearms and equip community members with trauma-related first aid training. Charles says it has produced positive results. “We found that the program is successful in improving the attitudes that young people have about using violence to settle disputes, particularly disputes related to disrespect,” says Charles.

Redefine American masculinity to change our country's relationship with violence and guns

As long as American masculinity is defined by power over others and the suppression of natural human emotions, Pollitt believes that men—and the rest of the world, as a result—will be condemned to this oppressive cycle of violence.

A concept that she always introduces early in her classes is that people who are hurting are the ones who are most likely to hurt other people. The men who are committing these violent acts with guns today were usually victims of or were exposed to violence as children. These men act violently as adults because they have not been provided with a better way to express their fear, anger, anxiety, frustration and pain.

Pollitt says we need to be proactive and intervene in boys’ lives so that they can change their relationship with themselves and with their ideas of violence. “As a society we need to do a better job of redefining what it means to be a man in this country and make sure we are redefining it in a way that allows men to be able to experience and express the full depth and breadth of their own humanity,” says Pollitt.

Changing our country’s definition of masculinity can seem like an unrealistically large task because of how deeply it is ingrained in our culture and daily behavior. But Pollitt proposes three ways where this change can begin.

At an individual level, parents and anyone else working with young boys and men should educate themselves on the social construction of masculinity on a deeper level. This is easier than it sounds, says Pollitt, who recommends setting aside an hour and a half to watch The Mask You Live In, an award-winning documentary by The Representation Project. She says the film will jump-start viewers’ understanding of gender norms and help them begin to redefine them in their own lives.

At a community level, Pollitt explains that we need to find a way to make boys feel safe expressing all of their emotions and teach them how to talk about feelings without fearing shame and stigma. She highlights the Men’s Center for Growth and Change in Philadelphia as an example of how communities can start engaging in this change. The nonprofit provides workshops, trainings, men’s groups and counseling services to help men learn to create relationships rooted in positive self-esteem, respect for others and nonviolence.

At an institutional level, Pollitt emphasizes the critical role that colleges and universities play in reshaping how our society defines gender. In order for communities to make change, they need a critical mass of people in those communities advocating for it. Universities can help create that critical mass.

“The fact that a Men and Masculinities course is available at Temple University is notable. We are not the only school offering a course like it, but this certainly isn’t the norm,” she says. Courses like Pollitt’s need to become the norm for all institutions of higher education because she says students don’t yet have a safe space to talk about the harm caused by this limiting construct of masculinity. “When there is no outlet, no safe space, no support—that’s when men can end up harming themselves or others out of desperation. As institutions, it’s our responsibility to find a way to reach them.”

Pollitt points out that her Men and Masculinities course continues to be one of the most popular courses offered by Temple’s gender, sexuality and women’s studies program. She regularly hears from students that the course gives them a better understanding of generational trauma, their own relationships with the men in their lives and their relationship with their own masculinity regardless of their gender. “I have no doubt that these students are already beginning to reimagine a healthier, less toxic masculinity and that they’ll raise a generation of boys who are less violent and more secure, caring and connected,” says Pollitt.

Evolve media's coverage of gun violence

Episodic crime reporting is a common approach used by news media that typically communicates the most basic details about a shooting, such as the age and condition of the victim, the number of gunshot wounds and whether or not an arrest was made. Law enforcement representatives are generally the narrators of episodic crime reports, and the perspectives of gun violence victims, co-victims and impacted communities are often missing.

The problem with episodic crime reporting is that it can lead news audiences to blame victims and reinforce stereotypes about the people and places where gun violence is most prevalent. It can also impede public support for public health efforts as solutions and prevention are rarely explored.

Working with a multidisciplinary team at the Philadelphia Center for Gun Violence Reporting (PCGVR), Beard recently uncovered the extent to which episodic crime reports can make shooting survivors feel dehumanized and add to their trauma in the aftermath of injury. This research study, which included 26 gun violence survivors cared for at Temple, is the first of its kind to explore the impacts of gun violence reporting on injured people.

The findings from this study provided inspiration for PCGVR’s Better Gun Violence Reporting Workshop in September 2022, which brought together local journalists, public health experts and community members to design ways to improve gun violence reporting in Philadelphia. Workshop participants created prototypes for better reporting solutions, which included a community center where newsrooms could lead workshops on citizen journalism, training in trauma-informed gun violence journalism, and utilization of an encrypted messaging system where community residents can share tips with reporters and build deeper relationships.

Beard is now seeking funding to research the effectiveness of the proposed prototypes. Her ultimate goal is to create a set of guidelines backed by her research that can become part of the journalism industry’s best practices. The result would be the development of trauma-informed crime reporters, journalists who are aware of the impact their work can have on victims on trauma.

Where Beard is focused on evolving the style in which crime reporting is done, two Temple deans propose an altogether different approach for media coverage of mass shootings: an evolution of what images are used to accompany news reports.

Historically, in the wake of a mass shooting, media outlets will use the same smiling photos when referencing the victims. But to these deans, this is an educational opportunity that is being missed.

David Boardman, dean of the Klein College of Media and Communication and former editor-in- chief of The Seattle Times, and Amy Goldberg, dean of the Lewis Katz School of Medicine, believe that more Americans would support gun reform if they better understood the damage that assault weapons have on human bodies. They are advocating for media outlets to publish the images of victims’ bodies after a mass shooting.

“Put on display—in newspapers, on television, across the internet—a photograph or three that can, finally, help the American public understand exactly what happens when a weapon designed for modern warfare is unleashed on innocent, unarmed people,” the pair wrote in a recent op-ed.

They point to past examples of shocking photojournalism sparking change, such as a 1972 Associated Press photo of a little girl burned by napalm, which inspired a change in Americans’ attitudes on the Vietnam War. More recently, the murder of George Floyd, which was caught on video and shared around the world, led to a racial reckoning and calls for police reform.

Boardman and Goldberg believe that graphic reporting on gun violence could similarly lead to a catalytic event that shifts Americans’ attitudes on gun reform. “This is not for shock and awe,” says Goldberg. “It’s for education and change.”

Move away from the term "gun control"

The language used by members of the media, politicians, researchers and other stakeholders when discussing gun violence can also impact our ability to work toward solutions. Specifically, the term “gun control” has become highly polarizing, and Roman says it detracts from the work of people advocating for common sense gun laws.

Seatbelts, cigarettes and the consumption of alcohol are all regulated in America, yet the term “control” is not used in conversations about their regulation. Instead, Roman says terms like “gun safety” help cut through the polarization and open up conversations about solutions for gun violence to a wider range of stakeholders. “There is lots of evidence that safety measures save lives,” Roman says. “There are so many aspects of safety, such as gun locks, training parents and safe storage, but all of that gets forgotten because of the polarization that comes with the term ‘gun control.’”

Gun control may also suggest overreach, and it has negative connotations for Americans who are concerned about maintaining their rights. But Roman points out that the proposed safety regulations that “gun sense” advocates are fighting for are not meant to restrict law-abiding adults from owning basic guns typically used for self-protection, target shooting, and/or hunting.

Putting it all together

In the first part of this series, Temple experts detail the unique set of circumstances that have caused the record-breaking levels of gun violence in America. In the second part, these experts lay out a variety of solutions that can help the country make significant strides toward ending gun violence. The takeaway is resoundingly clear: There is a path forward to stopping gun violence in America.

Temple’s experts are not only deeply invested in understanding the complexities of gun violence, but they are also committed to researching solutions that actively address the problem while inspiring the next generation to join and expand on their efforts.

The university is a part of Philadelphia’s Civic Coalition to Save Lives, joining city leaders, businesses, faith-based communities, nonprofits and other foundations in a comprehensive effort to take citywide ownership of and address Philadelphia’s gun violence crisis. The coalition plans to examine approaches that have worked in other cities and partner with city officials like Mayor Kenney to implement evidence-based strategies for reducing gun violence.

Temple’s Task Force on Violence Reduction, which includes Roman and Charles, recently launched its violence prevention website, which spelled out actionable measures the university can and will take to make campus and Philadelphia a safer place.

In November, Welbeck celebrated the opening of Temple’s Center for Anti-Racism. The center will host collaborative efforts to improve education, resources and opportunities available to the communities surrounding Temple and steer future generations of Philadelphians away from gun violence.

Temple faculty members recently took part in a civic hackathon, where leaders from across the city came together for a series of workshops to develop practical strategies for reducing gun violence.

Temple’s newly welcomed 12th president, Jason Wingard, has prioritized addressing gun violence and improving campus safety since the beginning of his tenure. In July, Wingard was joined by U.S. Senator Bob Casey (D-Pennsylvania) in meeting with Philadelphia students to discuss how gun violence has impacted their lives and explore solutions with the young generation.

Efforts like these give hope that one day the constant barrage of shooting reports will dissipate and we can begin to live, once more, without an unrelenting fear of being killed by a gun. There is plenty of work that needs to be done to get to that point, but experts working on the issue believe it’s within our grasp.

In the meantime, Jessica Beard will continue offering life-saving treatment to gunshot victims, Laurence Steinberg will continue exploring the adolescent brain to better understand their risk-taking behaviors and the rest of our experts will continue working toward a future where we are safe from guns.